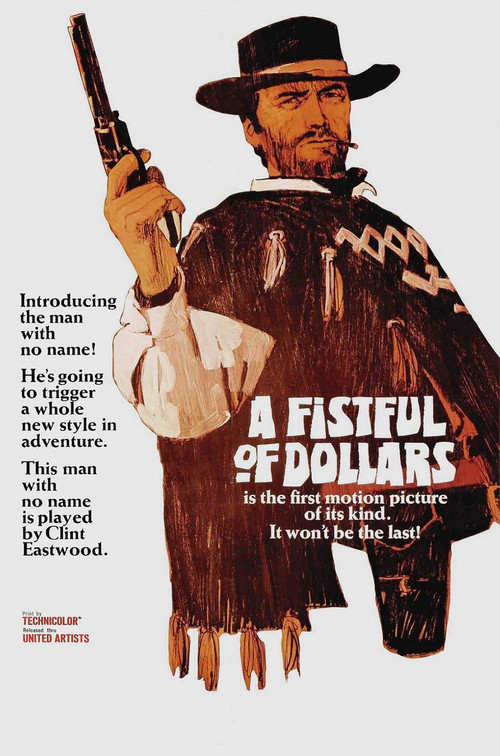

Younger film fans may find it hard to believe, but Clint Eastwood wasn’t always a badass. Prior to his iconic performance in “A Fistful of Dollars” (1964), Eastwood was best known to American audiences as Rowdy Yates, a kind-hearted supporting character on the popular “Rawhide” TV show. In fact, it was the opportunity to leave Rowdy’s friendly persona behind that most intrigued Eastwood about going to Spain to work for director Sergio Leone. “I decided,” Eastwood said, “it was time to be an anti-hero.”

No one could have predicted that “A Fistful Of Dollars,” released in Italy 50 years ago this September, would simultaneously launch Eastwood to international stardom and set the guidelines for one of the most unique and unexpectedly durable sub-genres in cinema history: the “Spaghetti Western.”

One can’t discount the role of kismet in the making of “Fistful.” For instance, Eastwood wasn’t Leone’s first choice. Many others, including Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson, were considered before Eastwood got the job. Fortunately for Clint, Leone couldn’t afford A-list actors. Eastwood’s previous film roles were limited to minor parts in movies about talking mules and giant tarantulas, so he came at a good price. He wasn’t expecting much from this obscure Italian production, joining only because it “sounded like fun.” In the spirit of a small-time venture, Eastwood supplied his own hat, pants, and cigars. He’d even wear the same boots he wore on “Rawhide.”

The genesis of “Fistful” occurred when Jolly Film, a mid-level Italian production company, struck a two-picture deal with Spanish and German firms. The first feature was to be “Bullets Don’t Argue,” the sort of traditional Western that Italian filmmakers had been shooting for years. The second was planned as a low-budget quickie using the same sets as the first. Jolly Film hired Leone, a fringe figure in Italy’s movie world, to direct the “B” side of the two-film arrangement.

Leone was bursting with ideas. Feeling that American Westerns had grown stale, he wanted to create an utterly lawless environment filled with enigmatic characters, the most striking of which was Eastwood as “The Man With No Name,” a mysterious fellow with a lightning-fast gun hand. Leone’s childhood friend Ennio Morricone composed the score for “Fistful,” his haunting style perfectly matching Leone’s violent eye candy. Leone loved Morricone’s work so much that he would intentionally let scenes drag a bit to accommodate an entire section of music. Their partnership would last several years, and albums of Morricone’s music would go on to sell millions of copies.

“Fistful” was Italy’s highest grossing movie of 1964 and pulled the Italian film industry out of a slump. Leone immediately followed up with two more Westerns, including “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” (1966). There were some initial bumps in the road, though.

When Japanese director Akira Kurosawa saw too many similarities between “Fistful” and his own film, “Yojimbo” (1961), he successfully sued Leone’s group for breach of copyright. Leone found himself in court again when Jolly Film claimed ownership of “The Man With No Name” character. This time the judge ruled in favor of Leone, saying that gunfighters were part of folklore and therefore in the public domain.

United Artists, which had found great success distributing the British-produced James Bond films in the United States, decided to release Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns. “Fistful” arrived first, in January of 1967. For a generation enduring a war in Vietnam and rejecting their parents’ more wholesome, idealized entertainment, Leone’s twisted version of a mythic West felt ideal. Most critics dismissed the movie as a collection of Western clichés taken to a grotesque level, but every sour review was met by the ringing of cash registers. The other chapters in the “Dollars” trilogy would hit America by the end of the year. Forget “The Summer Of Love” and “Sergeant Pepper”; for many moviegoers, 1967 was the year of “The Man With No Name.”

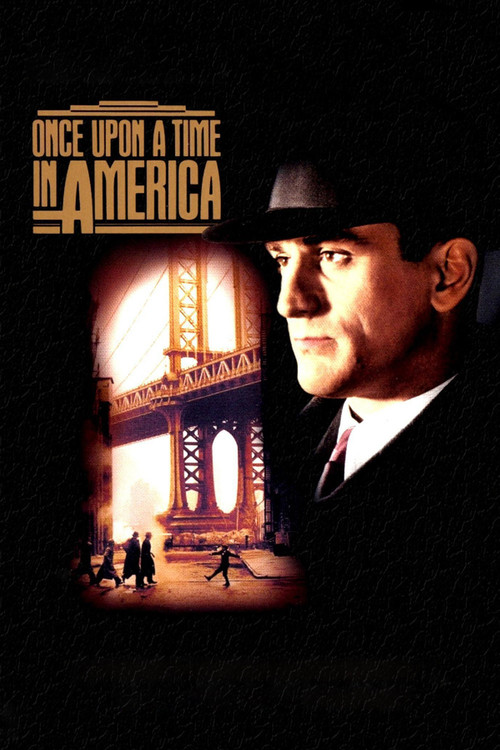

According to some sources, the Spaghetti Western boom of the next decade saw close to 500 features produced throughout Europe. Such actors as Franco Nero, Lee Van Cleef, and Terence Hill (real name: Mario Girotti) found a home in the genre. When Paramount Pictures got into the game and produced Leone’s classic “Once Upon A Time In The West” (1968), stars Fonda and Bronson were suddenly affordable.

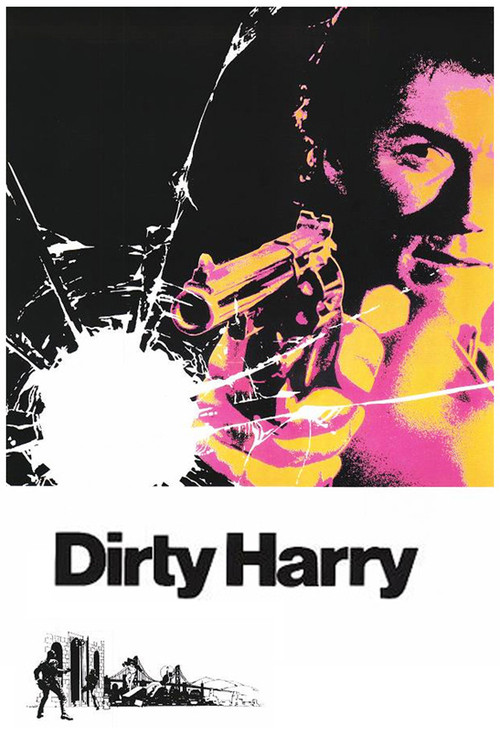

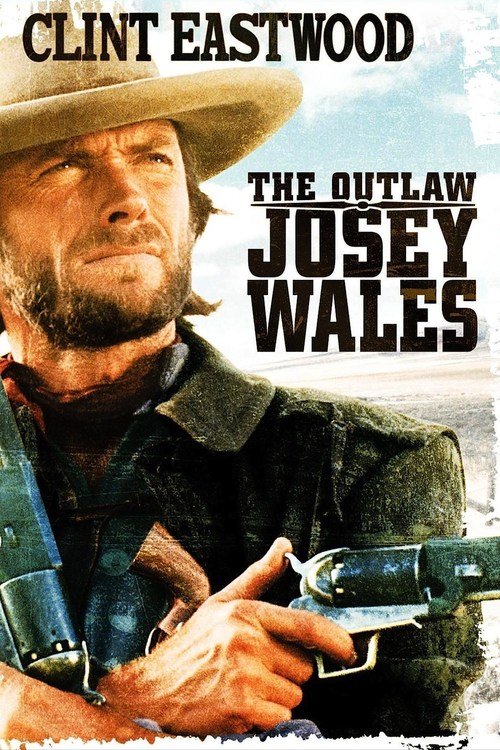

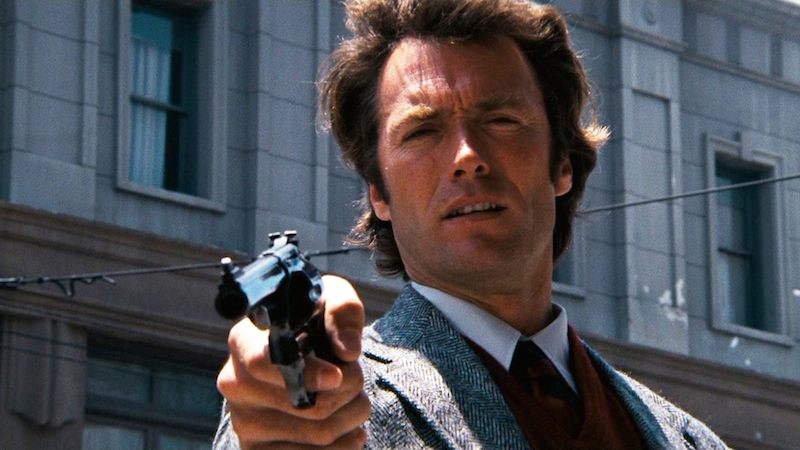

Just as the genre was peaking, Eastwood tipped his hat and moved on, although many of his future films, from “Dirty Harry” (1971), to “High Plains Drifter” (1973), “The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976), and even “Unforgiven” (1992) were informed by the work he’d done with Leone. It seems you can take the star out of the genre, but you can’t take the genre out of the star.

Occasionally, there’d been rumors of friction between Eastwood and Leone, although Eastwood was quick to thank Leone when he accepted his Best Director Oscar for “Unforgiven.” Film buffs also like to debate whether Leone made Eastwood, or Eastwood made Leone. There are good arguments for both sides, but there’s no clear-cut answer. We’re just glad they met.

FAQ about Spaghetti Westerns

1) How do I know I’m watching a Spaghetti Western?

There are certain tell-tale signs, namely the obviously dubbed voices. Leone and other Italian directors often shot without sound, and voices were added later. There are moments in “Fistful” where Eastwood is heard, but his lips aren’t moving. (On top of his other talents, who knew Clint was a ventriloquist?)

You might also notice that Spaghetti Westerns are usually fitted with titles that sound suspiciously like other movies. The original title of “Fistful of Dollars,” for instance, was “The Magnificent Stranger,” a knock off of “The Magnificent Seven.” In short, if the words “Dollar” “Gold” or “Coffin” are in the title, you’re probably watching a Spaghetti Western.

2) What’s the main difference between a Spaghetti Western and a Hollywood Western?

Italian screenwriters did away with American tropes that wouldn’t interest a European audience, namely Indians, cattle drives, and gallant sheriffs. Characters in Hollywood Westerns are usually motivated by things like honor and dignity. For the most part, in Spaghetti Westerns the motivation is plain old greed.

3) Who coined the term “Spaghetti Western?”

The credit generally goes to an Italian journalist named Alfonso Sancha, and the expression was originally meant as an insult. Some in the Italian film industry called the style “spaghetti and speroni (spurs).” Fortunately, no one noticed that many of these films were made with German financing; otherwise this article would be about “Wiener Schnitzel Westerns.”

4) Did the man really have no name?

This gets tricky. In the “Dollars” trilogy he’s known as “Joe,” “Monco,” and “Blondie,” although those could be dismissed as nicknames. Regardless, we have no idea how the guy got his mail.

5) What was the greatest Spaghetti Western of them all?

The nod usually goes to “The Good The Bad and the Ugly,” which was hailed by Quentin Tarantino as “the greatest achievement in the history of cinema.” (In my view, a slight overstatement on Quentin’s part). “Once Upon A Time In The West” gets a lot of votes, too. Hey, we like both! Check them out in our database, and get a taste of what we’re talking about. Easy on the garlic, though.