Several months ago, we lost Doris Day, a true American icon, at the age of 97.

What follows is the story of her best film, and the enduring, unexpected friendship that sprang from it.

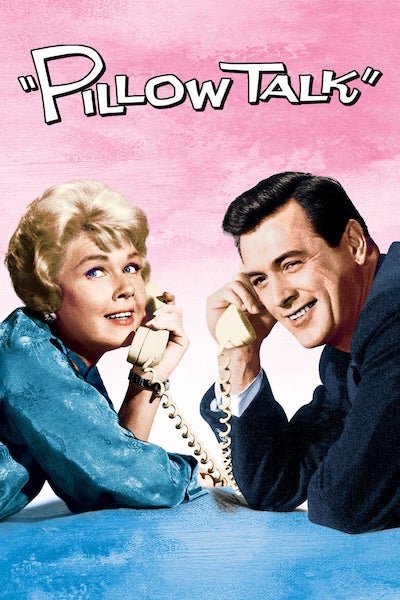

When producer Ross Hunter decided to make “Pillow Talk” early in 1959, many industry insiders doubted his judgment. After all, the golden era of romantic comedy was long past. William Powell had already retired, and Cary Grant had only a few films left in him, most of which were not romantic comedies.

The prevailing wisdom at the time was that the public wanted spectacles, westerns and war films. As if to prove the point, the original script for “Pillow Talk” had been floating around for over 15 years.

It was originally bought by RKO in 1942, when screwball comedies were still hot. The writers bought it back three years later when the studio hadn’t produced it. They then re-fashioned it as a play, sold it again, then ended up buying it back for the same reason.

Finally, 1958 they sold it once more, as a screenplay, to Arwin productions, headed by Doris Day’s manager and husband, Martin Melcher, who took it to Universal.

Melcher had married Doris in 1951 and now guided her career. Though he was clearly capable, he was also considered slippery and self-aggrandizing. Nobody much liked him. By contrast, most everyone loved Doris. She was known to be gracious, even-tempered, and completely professional.

Early on, she had wanted to be a dancer, but a car accident in her late teens badly injured her legs, so she decided to focus on singing. She worked with various big bands in the early ‘40s, and in 1945 scored a big hit at age 23 with a song called “Sentimental Journey.”

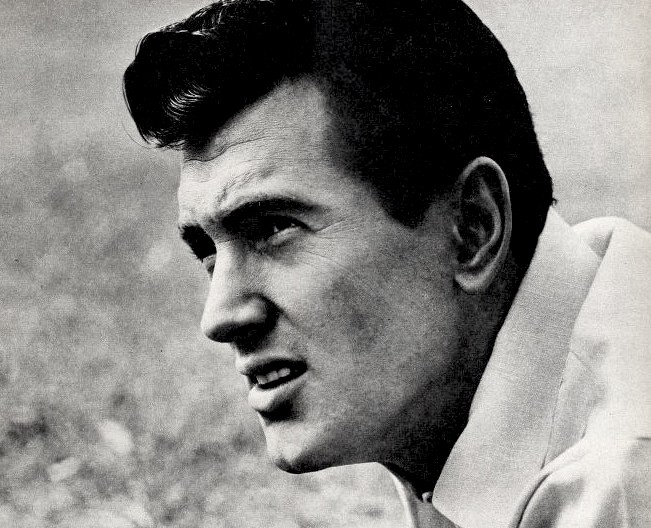

Rock Hudson would later say that the first time he was made aware of Doris Day was when he was overseas in the Navy, hearing that song. He was just 19.

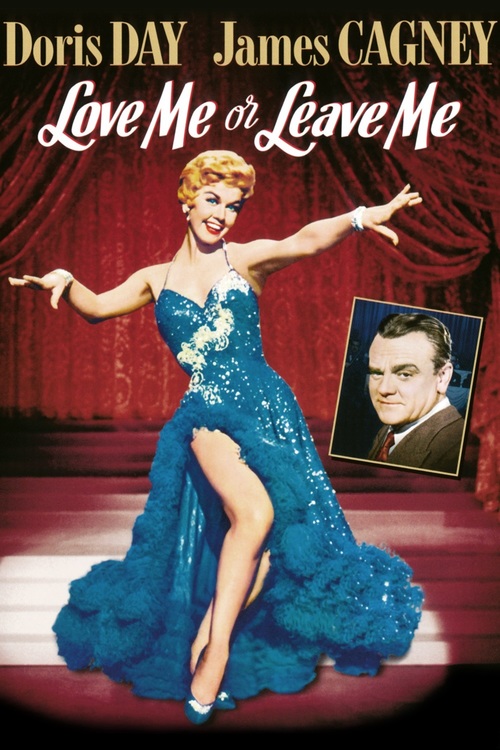

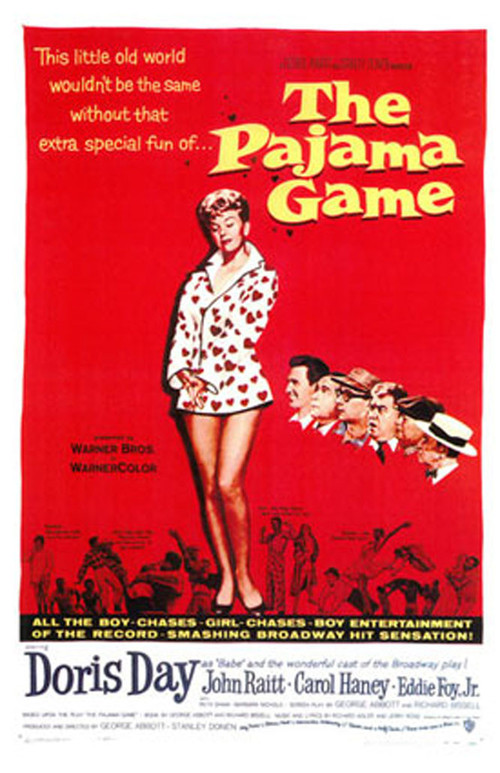

Doris’s natural talent and blonde beauty made her a natural for movies, and she made her film debut in 1948. Over the next 20 years she would most often appear in musicals, or movies that allowed her to sing. like “Calamity Jane” (1953) and “Love Me or Leave Me” (1955).

In 1956, she co-starred opposite James Stewart in Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” a serious film that demonstrated her acting range. (Her skill was no surprise to some of the acting giants who worked with her. For instance, both James Cagney and Jack Lemmon heaped lavish praise on her abilities).

Though Doris had a squeaky clean image as America’s “girl next door,” Ross Hunter had always felt she had lots of sex appeal, and wanted to exploit it. He was doubtless aware of Oscar Levant‘s oft-repeated quote about her: “I knew Doris before she was a virgin.”

Doris herself disliked this prudish perception of her, and obviously, having purchased “Pillow Talk,” Melcher agreed with Hunter that Doris could benefit from showing a sexier side. Thus the burning question became: who could generate sparks playing opposite her?

Hunter thought he had the answer: Rock Hudson. Just five years before, Hunter had cast the tall, strapping young man in a film called “Taza, Son of Cochise,” directed by Douglas Sirk. Hudson played a Native American warrior who appears shirtless throughout most of the film. Even with his impressive physique on full display, the film was just an average western.

However, on their next picture the team of Hunter, Hudson and Sirk hit pay dirt: 1954’s “Magnificent Obsession,” a remake of a 1935 melodrama that paired Rock with Jane Wyman.

“Obsession” was a big hit, and Hudson became an overnight star. Then he, Wyman, Sirk, and Hunter reteamed and scored again the following year with “All That Heaven Allows.”

Over this period, Ross Hunter would end up making seven pictures with Rock Hudson. “Pillow Talk” would be their final outing, though the producer would work with Doris on two more films: “Midnight Lace” (1960) and “The Thrill Of it All” (1963).

When Hunter first approached Rock to do “Pillow Talk,” the actor resisted. He had never done a comedy and felt he had no aptitude for it.

By this point, he was as big a star as Doris, having recently won an Oscar nomination for his role in “Giant.” But as a closeted gay man, he was always cautious about making waves, and also worried the film was too racy. There was even a sequence in the script when his character pretends he’s gay!

Finally, Rock actually met Doris, and they immediately hit it off. She persuaded him to take the part, telling him she knew he could do it and would help him. He would later say that she was his best acting teacher.

“Pillow Talk” would be shot in color, mostly on location in New York City.

To direct, Hunter hired Michael Gordon, who had guided Jose Ferrer to an Oscar in “Cyrano de Bergerac” in 1950, but had been blacklisted the following year. This would be the first feature film he’d directed in eight years. (Trivia note: Gordon was the grandfather of actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt).

Gordon would go on to fashion a colorful, bubbly confection centering on Jan Morrow (Day), a single interior decorator, who is forced to share a telephone party line with Brad Allen (Hudson), a playboy composer who lives nearby. This creates frustration, and the two haggle, bicker, and insult each other over the phone.

Brad eventually spots his nemesis, is immediately attracted, and decides to impersonate a rich Texan to get close to her. Tony Randall plays Jonathan, a millionaire who is both an old college buddy of Brad‘s and a client of Jan’s. He’s also begging Jan to marry him, with no success.

Finally, the inimitable Thelma Ritter is on hand as Jan’s boozy maid. A true scene stealer, she is perhaps best remembered as Jimmy Stewart’s nurse in “Rear Window” (1954).

The shoot itself was that rarity in the movie business: a fun, relatively smooth experience that resulted in a great film. The cast got along beautifully, knew they were making something extremely funny, and spent most of the time trying not to crack up and ruin takes. And the powerful chemistry between Doris and Rock was as evident on set as it was on screen.

“Pillow Talk” was a monster hit on release, one of the biggest box office successes of the year. It grossed close to eight million dollars in its initial release, having cost two million to make. Ross Hunter could now thumb his nose at all the doubters.

1959 was also a very competitive year, with releases like “North by Northwest,” “Some Like It Hot,” “Anatomy of a Murder,” and “Ben-Hur.” One of the few Oscars “Ben-Hur” didn’t win was best screenplay, which deservedly went to this film. “Pillow Talk“ would also bring Doris her one and only Oscar nomination.

The film’s success would spawn two sequels: “Lover Come Back” (1961) and “Send Me No Flowers” (1964). Doris, Rock, and Tony Randall would appear in all three. Only the last film fails to live up to the high standards of the other two.

Though they would never officially work again, Doris and Rock remained devoted friends for life. They even had pet names for each other: he called her Eunice; she called him Ernie.

Doris continued acting for another decade but gradually came to realize that her time in movies was passing. This became particularly clear when she found herself turning down the part of Mrs. Robinson in “The Graduate.” She could never have faced doing that role.

She made her last movie in 1968, the year her husband died. She only discovered after the fact that Melcher had left her bankrupt, and had also signed her up for a TV series on CBS. “The Doris Day Show” ran from 1968 to 1973. Meanwhile, she was suing Melcher’s business partner to try to get at least some of her $20 million fortune back.

Finally Doris retired to devote herself full-time to the cause of animal welfare. Reportedly, her concern for the treatment of animals was awakened when she witnessed abuse on the set of “The Man Who Knew Too Much.”

She ended up settling in the town of Carmel California, and there housed between 15 and 20 dogs at once. She soon settled into a happy retirement, attempting one final marriage that didn’t take.

In the early eighties, a sequel to “Pillow Talk” was floated that would have reunited the three stars, but it never came to fruition. Doris just wasn’t that anxious to return to the limelight.

Unlike his old pal and co-star, Rock Hudson kept working on screen and later on TV, starring in his own very successful series, “McMillan and Wife.” Sadly, he would never get the chance to retire.

In 1984, Doris re-emerged briefly to do a show about animals on the Christian Broadcast Network. Rock agreed to be her first guest. In publicity photos together, he appeared deathly ill, shocking his public. Two months later he succumbed to AIDS at the age of 59. He became the first major movie star to die of the disease.

Doris was heartbroken, but soldiered on. Twenty years later, she would lose her only son, Terry Melcher, to cancer. Again, she was devastated, but kept busy, looking to her many animals for comfort, and finding it.

Now, Doris is gone, and with her goes an era that reflected a more hopeful, optimistic America. Thankfully, we will always have “Pillow Talk,” which shows two devoted friends, and first class stars, in peak form.

So long, Eunice and Ernie!

More: Why Rock Hudson Was So Much More Than a Symbol of AIDS