In the roughly eighty outsize years he had on this earth, writer/director John Huston seems to have lived several lives and lifetimes. Those who remember him best for his occasional acting forays (most memorably as Noah Cross in “Chinatown”) should also explore Huston’s indelible work behind the camera.

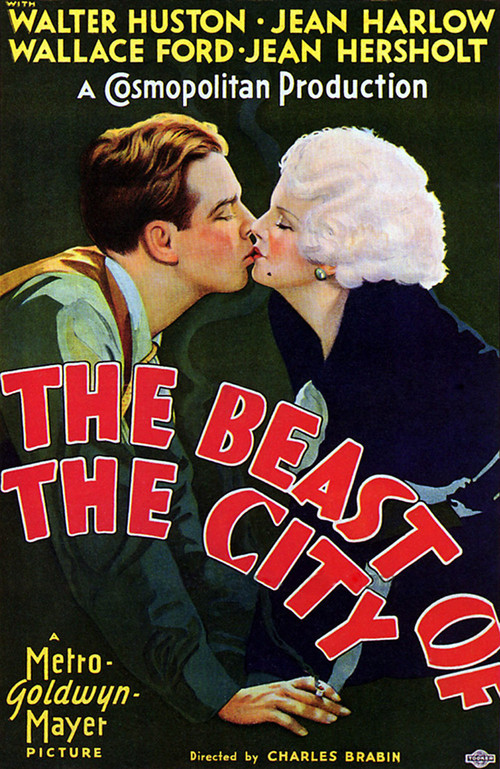

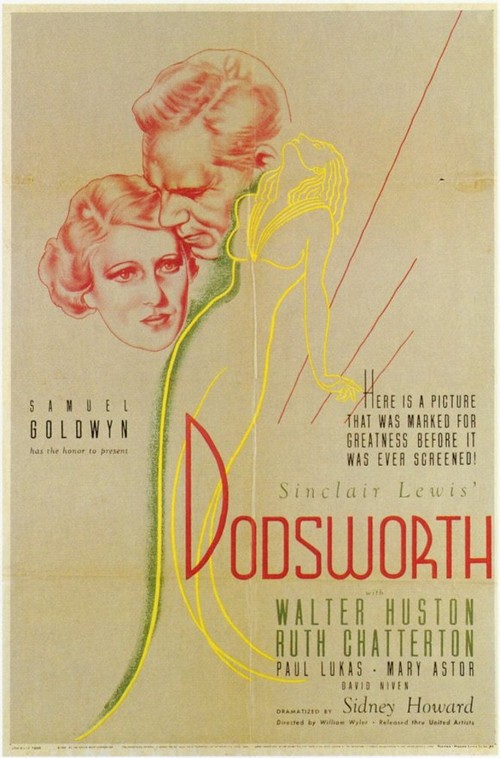

The tall, gangly son of noted actor Walter Huston, he started as a screenwriter, and by his early twenties was already scripting such high-profile Warner Brothers’ pictures as William Wyler’s “Jezebel” (1938), starring Bette Davis. Then, on the set of Raoul Walsh’s scorching “High Sierra” (1941) which he also penned, Huston would encounter Humphrey Bogart, a seasoned Warner’s supporting player who, with the younger man’s help, would soon make a late bid for stardom.

By this point, John had earned a chance in the director’s chair, and the feature he’d helm was a re-make of Dashiell Hammett’s bestseller, “The Maltese Falcon.” After Warner’s star George Raft foolishly turned down the starring role of private detective Sam Spade, saying he didn’t want to work with a first-time director, Bogie was tapped with Huston’s enthusiastic support. The film became an enormous success, with a cool, assured Bogart playing opposite Mary Astor’s Brigid O’Shaughnessy, a shifty femme fatale who needs help finding a jewel-encrusted statue of a falcon.

Henceforth Huston would direct (and sometimes write) most all his movies, achieving a career high with twin 1948 triumphs that once again featured his pal (and drinking companion) Bogart: “The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre” and “Key Largo.”

“Treasure” concerns three desperate men (Bogart, Tim Holt, and his dad Walter) who collaborate in a search for gold south of the border. However, their finding it may just prove to be their undoing. In the superb “Largo,” Bogie and Bacall end up trapped with gangsters in a hotel on the Florida coast just as a hurricane (both literal and figurative) approaches.

Two years later, Huston scored again in what remains one of the finest noir films on record: “The Asphalt Jungle,” a crackling nail-biter about the planning and execution of a daring jewel robbery, starring Sterling Hayden and Louis Calhern. (Also look fast for Marilyn Monroe in a bit part!)

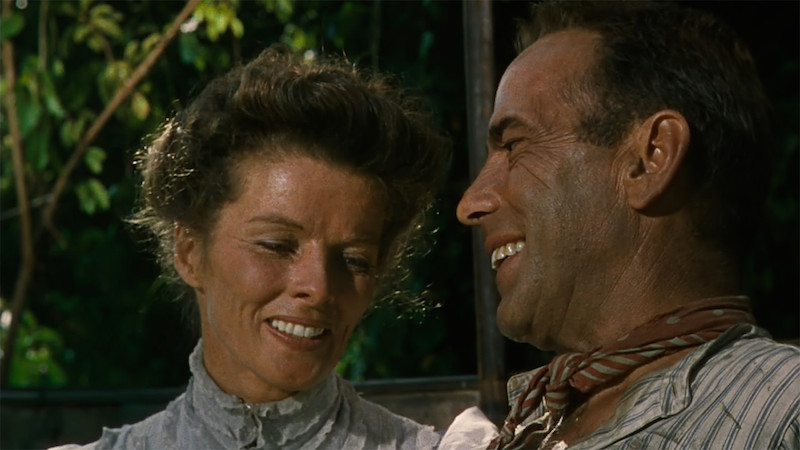

Then came Huston’s biggest triumph to-date: “The African Queen” (1951), the story of a disheveled, alcoholic skipper and female missionary thrown together by circumstance in the wilds of Africa circa World War One. Originally intended as a vehicle for Bette Davis years before, this first-time pairing of Bogart and Katharine Hepburn worked a charm, netting the aging actor his first and only Oscar.

By all accounts, the location shoot was as fascinating as the movie itself. For instance, reportedly Hepburn was so peeved by Huston and Bogart’s heavy drinking on-set that she restricted herself to water, causing a severe bout of dysentery, much to the delight of the boozers.

“Queen” was swiftly followed by the colorful, atmospheric “Moulin Rouge” (1952), a biopic of the artist Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. The film evokes all the vibrancy and bustle of late nineteenth century Montmartre, the time and place that served as the artist’s inspiration. A virtually unrecognizable Jose Ferrer does a shaded, appropriately melancholic turn as the diminutive painter.

By this point, it appeared that most everything John Huston touched would turn to cinematic gold. It may be the writer/director began to believe this himself, and got complacent. Certainly with success he could and did indulge in more real-life adventures; he was a keen sportsman and hunter.

Regardless, the ensuing twenty years would yield only a few good Huston films (notably 1957’s war drama “Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison”), and far too many releases unworthy of his talent (“The Barbarian and The Geisha,” “The Bible,” “Reflections In A Golden Eye”, “Sinful Davey,” and “The Kremlin Letter,” to name a few).

Thankfully, two films from the 1970s saw the director return to his old form: first, the subtly evocative “Fat City” (1972), featuring Stacy Keach and a young Jeff Bridges. Keach plays a veteran small town, small time boxer who’s at a crossroads, while Bridges is the newcomer who reminds Keach of his former, more hopeful self.

The second feature was the rousing adventure film from 1975, “The Man Who Would Be King.” Based on a Rudyard Kipling story, Huston had wanted to do “King” for decades. Here Sean Connery and Michael Caine portray two former soldiers in the nineteenth century who travel to remote Kafiristan to seek their fortunes. There, they manage to set Sean up as a deity, and the two are waited on hand and foot. Of course, the only risk lies in the locals discovering they’re being had.

Characteristically, John Huston never retired. For his uneven but entertaining “Prizzi’s Honor” (1985), a rare foray into comedy, he’d become the first and only person to direct both a parent (Walter in “Treasure”) and a child (daughter Angelica in “Prizzi”) to respective Oscars.

Fiercely proud of his Irish heritage, the director died of emphysema shortly after completing his reverential screen adaptation of James Joyce’s “The Dead” (1987), another family affair featuring a script by son Tony, and starring Angelica. It would serve as a fitting swansong to an amazing life and career.

More: Forty Years Later — 4 Things You Never Knew About “Chinatown”