How do you make a legendary film in a few weeks’ time, all with a budget that would make even the most miserly studio head giddily twirl his mustache? Ask Sidney Lumet.

Unquestionably, “12 Angry Men” (1957) is one of the finest films of the 1950s, with three Oscar nominations to its credit; but even so, the project had a skin-tight budget, (only $350,000 – a paltry sum for a film, even then). This forced first-time feature director Lumet to bob and weave to finish on-time and on-cost. So how did he pull it off?

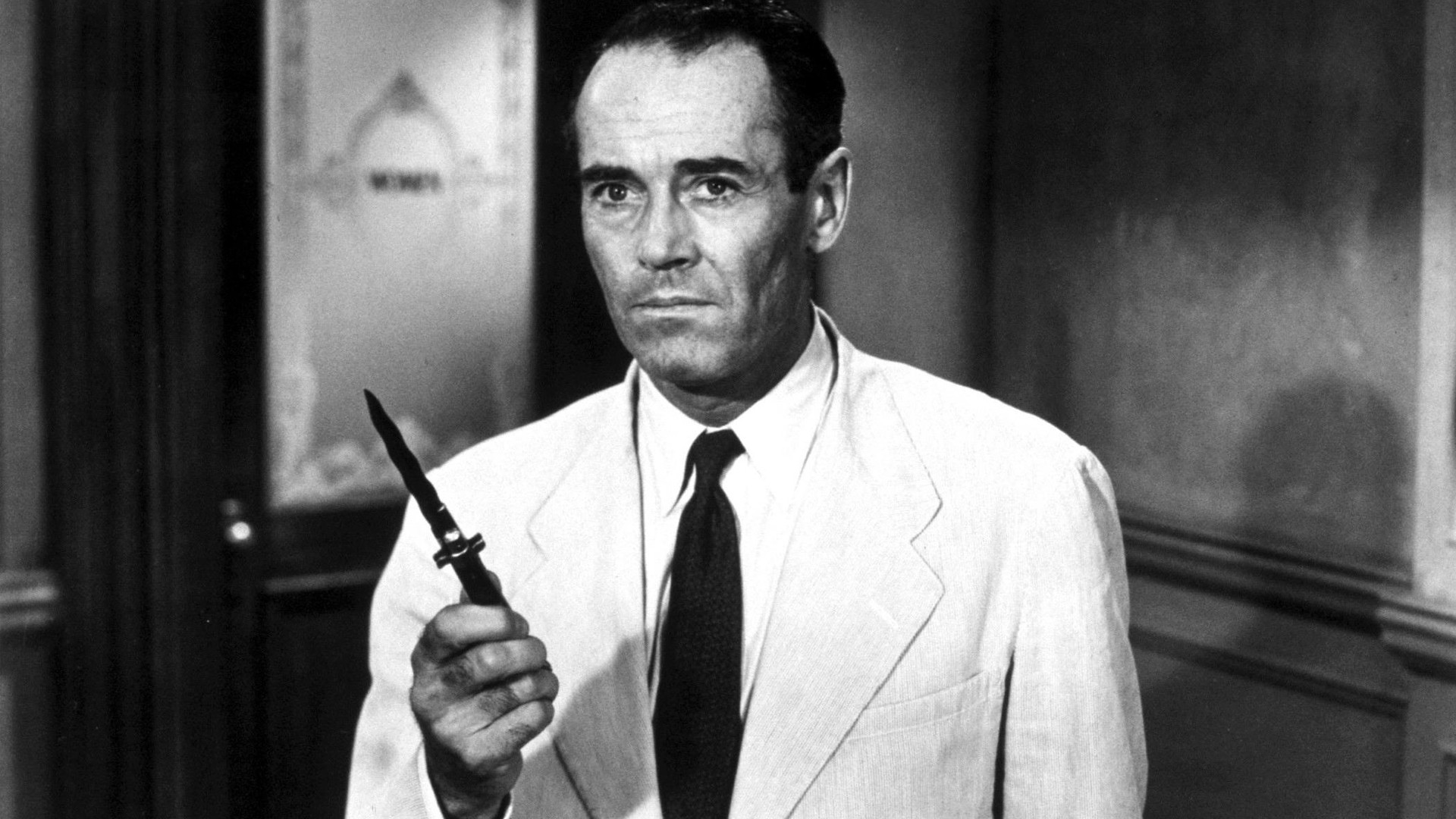

This tense film follows the contentious deliberations of twelve men, packed into a sweltering jury room, as they decide the fate of a youth accused of murdering his father. Lumet made the most of the confining premise by filming 93 of the 96 minutes on the same cramped 16 x 24 foot set. Even this solo venue was a cheap collection of sticks that Henry Fonda (AKA Juror 8) famously complained “looked like shit”, comparing it unfavorably to the lavish Hitchcock soundstages he’d just stepped off of when filming “The Wrong Man.”

To make the most of the time spent and limit the need for re-shoots, as well as give his cast a taste of what a fractious jury room would feel like, the actors rehearsed for two exhausting weeks in their cramped space. They immediately began filming afterwards – and (again) due to limited resources, wrapped shooting in 21 days — very unusual for a feature-length Hollywood film.

To create visual interest on the one small ragged location was a minor miracle and a blueprint that low-budget filmmakers like Sam Raimi (“The Evil Dead”) still follow today. Lumet and cinematographer, Boris Kaufman (of “On the Waterfront” fame), altered shot levels and lenses to create the illusion of changed space. Lumet wrote, “I shot the first third of the movie above eye level, shot the second third at eye level, and the last third from below eye level. In that way, toward the end the ceiling began to appear. Not only were the walls closing in, the ceiling was as well. The sense of increasing claustrophobia did a lot to raise the tension of the last part of the movie.” In the film’s last shot, he observes, he used a wide-angle lens “to let us finally breathe.” It is a stunning effect.

But the cost cutting didn’t stop there.

Lumet realized he could eliminate expensive down time between shots by only moving the camera when absolutely necessary. This meant shooting all the sequences that required one specific camera angle and lighting configuration at one time, regardless of the order of scenes. Any camera movement at all (or transition from day to night) was precious time wasted. This was partly because, in another cost saving maneuver, Lumet hired mainly hard-working but inexperienced longshoremen instead of a standard Hollywood technical crew to haul the lights around.

This static approach not only meant potentially filming two sides of a conversation weeks apart, it also required constantly modifying the perspiration on an actor to show passage of time. “With every scene,” Lumet told Life magazine in 1957, “we stood before the actor with an atomizer, trying to figure out whether or not to squirt on sweat and, if so, just how much to squirt.” To squirt or not to squirt…

Lead actor Henry Fonda joined in on the penny-pinching, agreeing to defer his salary until the movie started to make money. However, even with the film’s budget austerity, the movie didn’t turn a profit for many years, so Fonda went home without a check.

But Fonda wasn’t bitter. In fact, he regarded it as one of the three best films he ever made, up there with “The Grapes of Wrath” (1940) and “The Ox-Bow Incident” (1943). Fonda hated watching himself on-screen, so he tended not to see his own films, but he caught a good bit of this one in the projection room. Before turning to leave, the famously reticent actor faced Lumet and said, very softly: “Sidney, it’s magnificent.”

Of course, he was right.

Didn’t find what you’re looking for? Keep browsing for the right movie to watch tonight on our curated database. Using our search filters, you’ll never spend too much time deciding on a movie again. The best movies to stream are just a click away!