As so often happens in Hollywood, the most famous and beloved dance team in the history of movies was the result of a happy accident. The year was 1933, the studio was the financially strapped RKO, the film a Dolores Del Rio vehicle called “Flying Down to Rio.”

Ginger Rogers was a 21-year-old actress and hoofer who already had an extensive Hollywood resume of 20 films to her credit. She’d graduated from work as an extra, to small walk-on parts, to playing girls in the chorus. Most recently she’d moved up to appearing in two Busby Berkeley pictures, the quintessential backstage musical, “42nd Street” and its follow-up, “Gold Diggers of 1933.” Ginger got the chance to play the supporting role of Honey Hale in “Flying Down to Rio” simply because the actress that had been cast decided to get married instead.

Fred Astaire, twelve years Ginger’s senior, was already a star, but in a different medium. Over the past fifteen years, the gifted dancer, singer, and choreographer had made a name for himself on Broadway and the London stage in a series of musical comedies, paired with his sister Adele.

Now he was at a career crossroads. His vivacious, talented sister had just retired to marry a British aristocrat. On his own for the first time in his life, the intensely ambitious Astaire knew that with the Depression crippling Broadway, his best opportunity lay in Hollywood.

He had a rough start. Thin, bald and not classically handsome, the camera did not love him — at first. Hollywood was hardly clamoring for him the way his stage audiences once had. The hasty comment on his first screen test said it all: “Balding. Can’t act. Can’t sing. Can dance a little.”

As of 1933, he’d done precisely one picture, performing some steps with the game but rather clunky Joan Crawford in “Dancing Lady.” Playing himself, he received sixth billing, but did get the chance to wear the top hat, white tie and tails that would soon become his trademark. Given how new he was to films, he would actually be billed under Ginger for “Flying Down To Rio.” That’s the first and last time this happened.

From the start, it was clear that Astaire’s dancing skills way exceeded his new partner’s. But the scrappy actress had natural ability, as well as the drive to learn. In Fred’s words: “Ginger had never danced with a partner before. She faked it an awful lot. She couldn’t tap and she couldn’t do this and that … but Ginger had style and talent and improved as she went along. She got so that after a while everyone else who danced with me looked wrong.”

Their first number together, “The Carioca,” became a highlight of “Flying Down to Rio,” and RKO started talking about promoting them as a team. Astaire, who’d just shed sister Adele as his longtime partner and wanted to establish himself as a solo performer, mightily resisted at first, telling his agent it was out of the question.

Still, he couldn’t very well ignore the praise he and Ginger were receiving from critics, and finally agreed to another pairing with her in “The Gay Divorcee” (1934). This movie would be built around them, with both their names above the title. Based on the successful Cole Porter Broadway musical, “Divorcee” marked the only time Fred played a character on-screen that he’d originated on-stage. It proved to be another big hit for RKO, and featured such evergreen classics as “Night and Day” and “The Continental,” which became the first recipient of an Oscar for Best Original Song.

“Divorcee” not only demonstrated that Astaire-Rogers could carry a film; it proved they were a sensation. The four films that followed in quick succession over the next two years only reinforced that fact, most notably 1935’s “Top Hat” and 1936’s “Swing Time,” which many believe to be their best film.

Then, in 1937 the studio started to see diminishing box office results, even though the films — and the dancing — remained solid. First, “Shall We Dance” did only modestly well, even though it featured a Gershwin score and the return of Edward Everett Horton, who’d scored as Fred’s foil in both “Divorcee” and “Top Hat.” (Eric Blore, sublime as Fred’s British valet in “Divorcee,” “Top Hat” and “Swing Time,” was also on hand.)

The decade — and the partnership — closed out with “Carefree” (1938), an 80 minute picture which included just four Irving Berlin songs, and 1939’s “The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle,” a biopic about the famous pre-World War I dance team.

By this time, neither Astaire nor Rogers were sorry to part. Fred still wanted to prove himself as a single performer and dance with other partners, while Ginger wanted to pursue dramatic roles. Without question, she’d worked particularly hard in the partnership: Fred and choreographer Hermes Pan would usually work out all the steps in advance, and then, working tirelessly with Pan, she’d have to learn them cold. Only when she had would Fred reappear. Still, she often provided useful suggestions which got worked into the sequences. Both men respected her instincts enough to listen.

Over the six years she worked with Astaire, Ginger had cemented her stardom and vastly improved her dancing skills, but at a price: Fred was, in truth, a somewhat distant, exacting perfectionist who felt cutting and fancy camera angles distracted from the audience’s focus on the dance itself. So his preference was always to film dance sequences with a stationary camera in one continuous take. (His explanation: “Either the camera will dance, or I will.”) Retakes were often numerous, and torturous for poor Ginger, who was always encased in high heels. More than once, she had to change her shoes on the set, because they were filled with blood. She never complained.

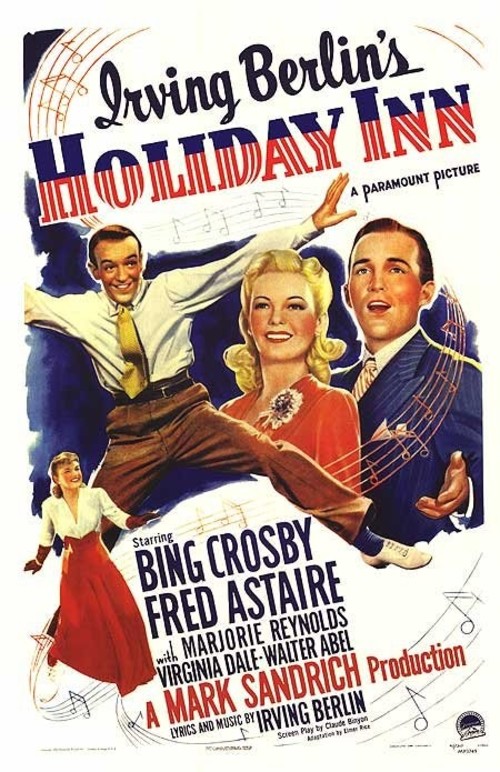

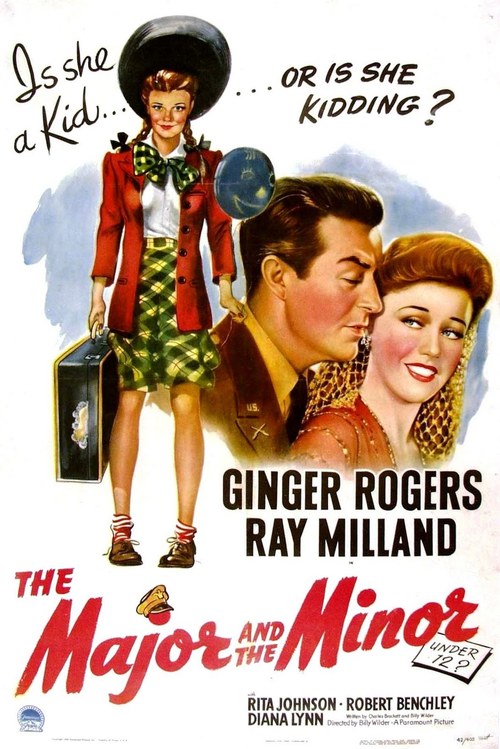

Ginger knew she could do a lot more than sing and dance. She’d already won praise for her role in 1937’s “Stage Door”; she wanted to do more films like it. While Fred moved on to musicals like 1942’s “Holiday Inn” and “You Were Never Lovelier,” Ginger distinguished herself in “Kitty Foyle” (1940), a touching drama that netted her a Best Actress Oscar. She also starred in Billy Wilder’s first directorial effort, a winning comedy called “The Major and the Minor” (1942), where her character masquerades as a little girl to save on train fare.

Fast-forward seven years: following their successful teaming in “Easter Parade” (1948), Astaire was all set to do another picture with Judy Garland at MGM called “The Barkleys of Broadway.” Sadly, at this point Garland’s pill addiction caught up with her, and she had to drop out of the project. Ginger, whose career was dipping somewhat, was only too happy to step in. This would be the team’s only color film, and their only picture not shot at RKO.

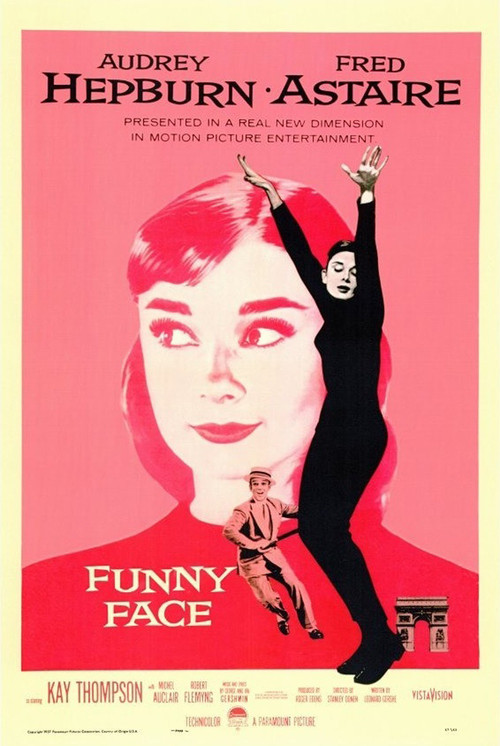

Critics and audiences were thrilled by their reunion, but alas, the pair had no inclination to team up again. Of the two, Astaire would go on to a more successful later run, starring in lush Technicolor musicals like “The Band Wagon” (1953) and “Funny Face” (1957), and also occasionally venturing into dramatic roles (most memorably, in 1959’s “On the Beach”). Ginger also kept busy doing TV appearances and the occasional film over this period.

Fred passed on in 1987, Ginger in 1995. Both were well aware of the legacy they’d left behind. How best to explain the particular magic they created together? Clearly, several factors were at play: First, Ginger was just the right height and body type for Fred. Second, her beauty and physicality compensated for Astaire’s angular, less-than-photogenic appearance, which recalls the famous quote attributed to Katharine Hepburn: “He gave her class; she gave him sex.” Third, he was the more gifted dancer and singer, but she was always inspired to meet his standard. Fourth, she was the more skilled, expressive actor, and Astaire’s performances improved from playing off her. Finally, they simply had amazing chemistry — and who can explain that?

Again, it was Fred, never effusive in praising his dancing partners, who captured it best: “All the girls I ever danced with thought they couldn’t do it, but of course they could. So they always cried. All except Ginger. No no, Ginger never cried.”