It is mystifying but true that when Alfred Hitchcock first visited Hollywood in the late thirties, none of the major studios was willing to offer him a contract — that is, until independent producer David O. Selznick stepped up.

It hardly seemed like a huge risk for Selznick (then MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer’s son-in-law), since Hitch had been directing for over 15 years in his native England, only recently helming such well-received features as “The 39 Steps” (1935) and “The Lady Vanishes” (1938).

Hitchcock’s first film stateside, an adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s novel, “Rebecca,” would become the only one of his films to win Best Picture at the Oscars.

This fact surprises many, since “Rebecca” is not among the first Hitchcock entries we tend to think of today. Certain later films, like “Vertigo,” “North by Northwest,” and “Psycho,” are far better known.

The heavily atmospheric “Rebecca” is a subtler affair — part romance, part ghost story, about a pretty but timid traveling companion (Joan Fontaine) who falls in love with a dashing widower, Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier), while accompanying an older lady in Monte Carlo.

Maxim eventually proposes, and she accepts. Once wed, they return to Manderley, Maxim’s massive estate in England. There she feels haunted by the presence of his deceased first wife, Rebecca, who seems to have been everything she isn’t: beautiful, confident, well-born. Soon she begins to doubt her new husband’s love, and her own sanity.

Hitchcock used deep focus photography to create an atmosphere of dread and isolation. Fontaine’s character appears tiny in the empty, cavernous environs of Manderley. She is utterly out of her depth and petrified. And Hitchcock shoots his scenes so we feel the same way.

Fontaine was not the first choice for this key role, since she was not yet an established star, unlike her elder sister Olivia de Havilland, who was also considered but proved unavailable.

Olivier, fresh off his success playing Heathcliff in “Wuthering Heights,” lobbied hard for his soon-to-be wife Vivien Leigh to get the part, but that didn’t work out either.

Thus he was bound to resent Fontaine, and treated her coldly on the set. Reportedly, Hitchcock told Joan that Olivier was not the only one who disliked her. Basically, the whole production was against her.

The director did this simply to boost her performance, which called for a mix of insecurity and fear bordering on terror. While cruel, his ruse succeeded.

Hollywood still boasted a robust British colony of actors, and many of them rounded out the cast: George Sanders, Gladys Cooper, Nigel Bruce, Leo G. Carroll, Reginald Denny, and the crusty, imposing C. Aubrey Smith.

Judith Anderson, who nearly steals the film playing Mrs. Danvers, the forbidding housekeeper still obsessed with the first Mrs. de Winter, actually hailed from Australia.

Screenwriters Robert E. Sherwood and Joan Harrison made Mrs. Danvers younger than in Du Maurier’s book, injecting a subtle note of sexual obsession. Hitchcock gave Anderson one key bit of direction that made her seem all the more terrifying: he told her not to blink.

The notoriously hands-on producer Selznick was perhaps Hitchcock’s biggest challenge. Viewing himself as a creative partner, Selznick would pore over the dailies and write lengthy memos with various suggestions, mainly relating to performances and story continuity. Hitch ignored virtually all of them.

The director was accustomed to a degree of autonomy back in Britain, and was stunned at first by Selznick’s intrusiveness. Thankfully, the producer was often distracted at this juncture, as he was overseeing perhaps the most anticipated release in movie history — for “Gone With the Wind.”

Hitch was also shrewd enough to know how to control the final outcome of his film. In those days of the fabled “studio system,” the word “auteur” had yet to be coined. Directors handed off their pictures when shooting wrapped; they did not see them through the editing process.

Fearing what Selznick might do in post-production, Hitch edited his movie in the camera, shooting just what he intended be used, and depriving his producer of lots of takes and shot variations to play with. His meticulous advance planning of every shot and angle served him well here, as it would on so many other films to come.

“Rebecca” was a hit on release. In the future, if Hitch shot in England it would be by choice, not necessity. Beyond its Best Picture win at the Oscars, the film also took home the statuette for George Barnes’s moody cinematography. In addition, Olivier, Fontaine, Anderson were all nominated, as were Sherwood and Harrison for their note-perfect script.

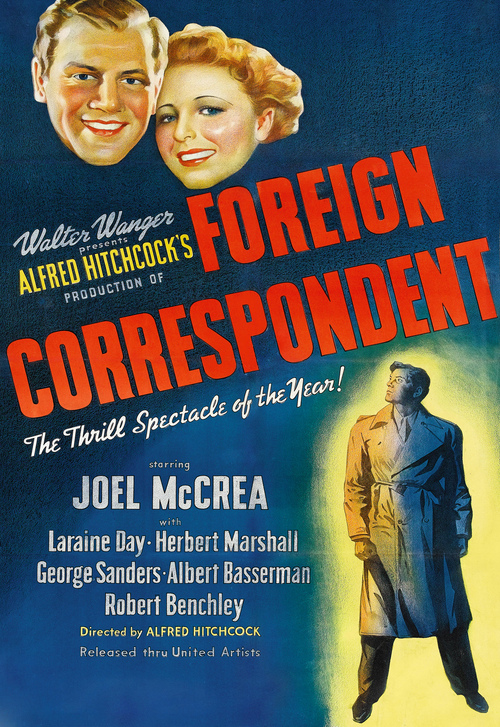

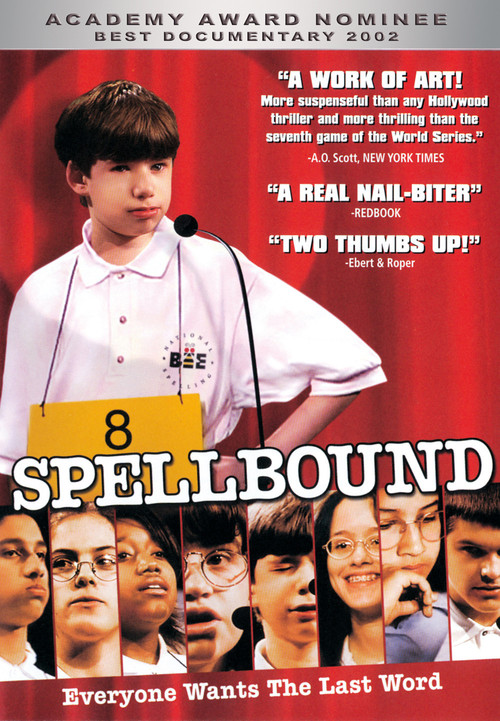

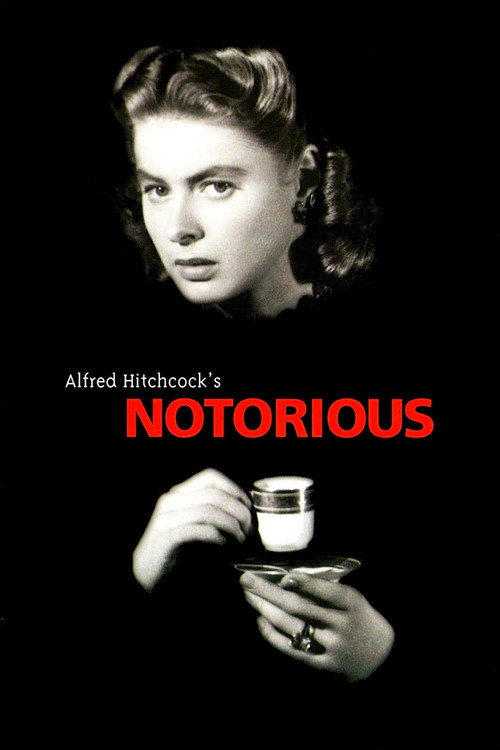

As the years passed, the Oscars were increasingly unkind to Hitchcock, making him pay for his commercial success. All four Hitchcock movies nominated for Best Picture happened between 1940-45 (for “Rebecca,” “Foreign Correspondent,” “Suspicion,” and “Spellbound”), along with three Best Director nods. Over the rest of his career, he’d earn only two more nominations for Best Director, and he never won a competitive Oscar.

By the 1950s, the conventional wisdom was that Hitchcock could only make one kind of picture, and that this lack of versatility made him somehow unworthy compared to contemporaries John Huston, Howard Hawks, John Ford and William Wyler.

When the Academy finally woke up and awarded the Master of Suspense the Irving Thalberg Award for lifetime achievement in 1968, it was too late. Hitchcock accepted the award and gave the shorted acceptance speech ever: a simple “Thank you.”

We respond “No, thank you!” to the man Entertainment Weekly cited as the greatest film director of all time in 1996.

And if you want to see the movie that announced this genius to America and the world eighty years ago, catch the hypnotic, ever fabulous “Rebecca.”

More: Hitchcock — The Story Behind the Scariest Man in Hollywood