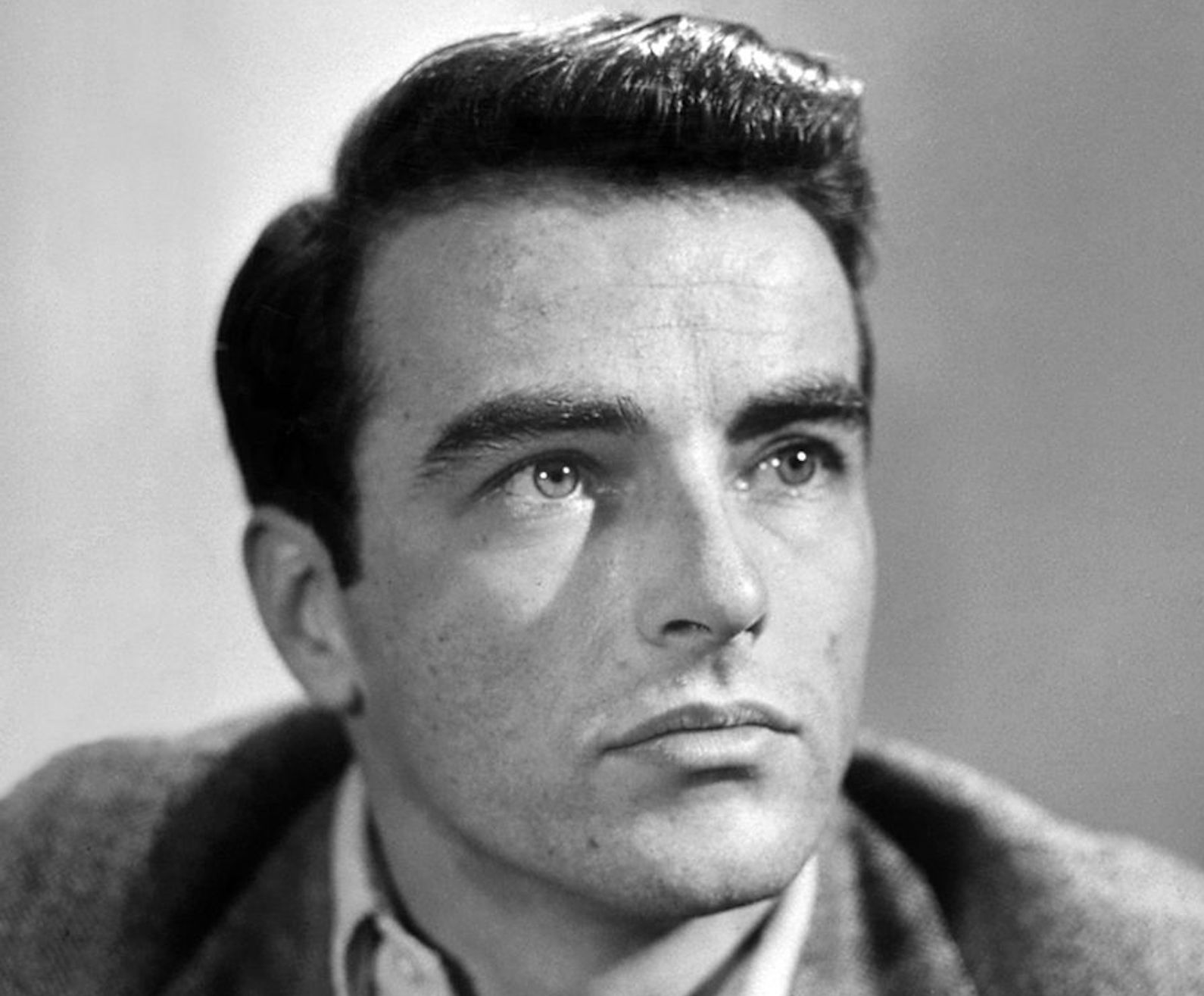

By the age of thirty, Montgomery Clift seemed to have everything: youth, beauty, talent, and the prospect of a lucrative film career with limitless possibilities.

Along with his friend and colleague Marlon Brando, Clift was the most visible and gifted of a new generation of movie star who’d been trained in “the Method” at Lee Strasberg’s Actor’s Studio. The Studio’s fundamental goal was to help actors inhabit their characters more fully in order to achieve greater realism and intensity in their performances.

Yet Monty, as he was known, could never fully enjoy his success. Professionally, he struggled continually with reconciling the deadly serious business of being a great actor with the crasser, more commercial considerations of Hollywood. Temperamentally, he was sensitive, introspective, and somewhat melancholy — the very traits that defined many of his roles. And his closeted homosexuality was an ongoing source of guilt and conflict. At the same time, he was enormously driven and dedicated to his craft, and could appear arrogant in demanding as much of his fellow players as himself.

He had a few very close friends, including Elizabeth Taylor, with whom he starred in “A Place in the Sun.” She adored him and worried about him, with good reason. First, though much in demand throughout most of the fifties, Monty was notoriously picky about which parts he accepted, which, in Liz’s view, undermined his ability to reach his full potential. (Monty would end up turning down “Sunset Boulevard,” “High Noon” and “East of Eden”). Ironically, this last movie would launch the young actor who most resembled Clift: James Dean.

Beyond this, Taylor was well aware of Monty’s inner demons and fragile health (he suffered from dysentery and colitis for much of his life). She observed first-hand his increasing reliance on pills and alcohol as the years went by, and felt powerless to alter his self-destructive course.

Edward Montgomery Clift was the product of an upper-middle class family from Omaha who lost all their money in the Depression. Reportedly, his banker father was bigoted and often abusive; much later, it’s claimed that in scenes requiring rage or anger, Monty would dredge up his deep-seated resentment towards his Dad. His mother, by most accounts, was a tireless social climber and snob.

Unlike his two siblings, Monty always struggled in school, but found his calling in the theater at an early age. No doubt this colorful world of make-believe also served as a refuge and escape from his home life. He made his Broadway debut at age 15, and by the time he moved to Hollywood ten years later, he was an acting veteran.

Monty always knew how to make an entrance. He resolved not to sign any studio contracts before performing in at least two films and (hopefully) earning a degree of success. As he later related it: “I told them I wanted to choose my scripts and my directors myself. ‘But sweetheart,’ they said, ‘you’re going to make a lot of mistakes.’ And I told them, ‘You don’t understand; I want to be free to do so.’” As it happened, he made few mistakes at the outset, and stardom came swiftly.

In his screen debut, Monty played John Wayne’s adopted son in Howard Hawks’ classic Western, “Red River.” Critics and audiences alike were taken with this stunningly handsome young man who stands up to the larger-than-life Duke. (Clift would get the chance to play opposite Wayne one more time, but declined the role of “Dude” in “Rio Bravo” that went to his friend Dean Martin. The politically liberal Monty didn’t want to work again with the far-right Duke, or the equally conservative Walter Brennan).

Though “Red River” was technically Clift’s first film, shot in 1946, its release was delayed due to litigation brought by Howard Hughes, who claimed the storyline was too close to his production of “The Outlaw” (1943). So Monty’s second film- Fred Zinnemann’s “The Search” (1948) actually came out first.

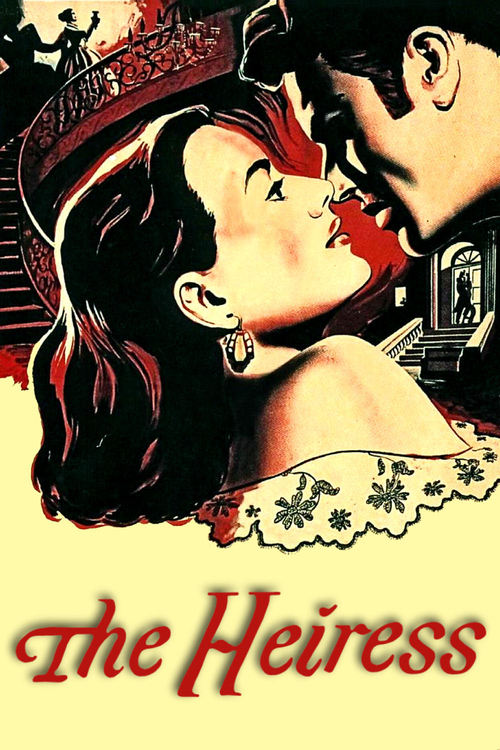

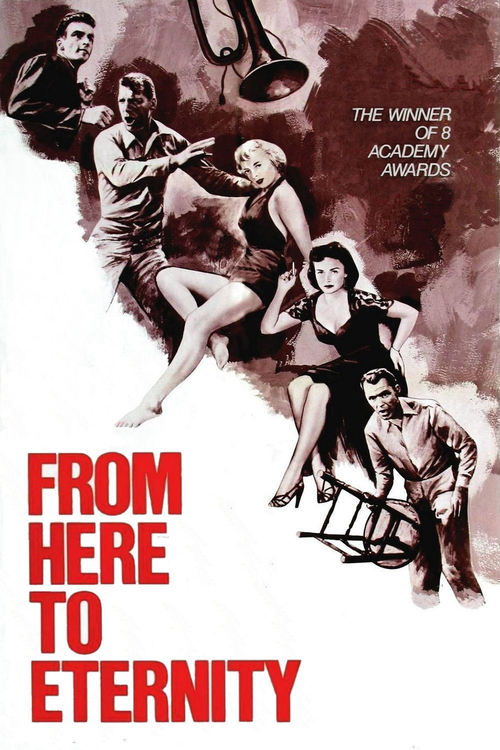

Here Clift is a soldier who helps a boy find his mother in a crumbling post-War Berlin. This showcase part won him his first Oscar nod. (He’d be nominated twice more over the next five years for “A Place in the Sun” and “From Here to Eternity,” which reunited him with director Zinnemann).

One story demonstrates just how respected Clift was in the industry at the time. Burt Lancaster, an even bigger star who got first billing on “Eternity,” was so nervous to play his first scene with Monty that he was literally shaking. Lancaster was a natural performer who’d never been “Method”-trained and was somewhat intimidated by the stars who had, most notably Clift and Brando.

In 1956, Clift was reunited with Liz Taylor for “Raintree County,” a period romance set during the Civil War. One night, after dinner at Taylor’s house, Clift fell asleep at the wheel driving home and smashed his car into a telephone pole. Though Clift would survive, the accident necessitated plastic surgery on his face, which permanently changed his appearance. The intense physical and psychological pain he experienced led to an uptick in Clift’s consumption of alcohol and addictive pain medications. A friend would refer to the following decade as “the longest suicide in Hollywood history.”

Over time, the abuse took a heavy toll. Both his career and personal life suffered as Monty’s behavior became increasingly erratic. On the set of “The Misfits” (1961), Marilyn Monroe, who had only a year to live herself, famously commented that Clift was the only person she knew who was worse-off than she was.

Still, his raw talent never left him, and that same year Clift would earn his fourth and final Oscar nomination (this one for Supporting Actor) playing a mentally disabled man sterilized by the Nazis in “Judgment at Nuremberg.” Though Monty’s difficulty in remembering lines by this point forced director Stanley Kramer to let him improvise, the resulting scene is one of the most affecting in the whole film.

By the mid-sixties, Clift’s health was steadily deteriorating, his film career all but dead. Elizabeth Taylor rescued her friend once again by demanding he co-star in her upcoming film, “Reflections in a Golden Eye.” But before production could begin, Clift died in New York City of a massive heart attack in July, 1966. He was just 45. (Fittingly, Brando would fill in for Monty in “Reflections,” but the film still sank at the box office).

Clift knew that more and more, both the industry and the press thought him eccentric and unpredictable. They found it exceedingly difficult to control — or pigeon-hole — him. For Monty, it was all about maintaining a modicum of artistic integrity. This became virtually his only lifeline. “Look, I’m not odd,” he once said. “I’m just trying to be an actor; not a movie star, an actor.”

Montgomery Clift always breaks your heart. You can always sense his pain and vulnerability on the screen. Like Liz Taylor, you want to help him, but he’s just out of reach. And then you consider the waste, the lost promise. He only completed 18 movies; had his demons not overtaken him, he could have left us an even richer legacy.

I feel this sadness most acutely when watching either “Red River” or “Judgment at Nuremberg.” Separated by less than fifteen years, these two outstanding movies bookend the career of a brilliant star destined to burn out way too soon.