There are just a few authentic geniuses in the history of cinema whose names and work must be remembered. High on that list is Jacques Tati.

Known for his portrayal of Monsieur Hulot, the bumbling innocent trying to navigate a bewildering modern world, Tati directed only six feature length films over a twenty-five year period. Ranked 46th on Entertainment Weekly’s list of the 50 Greatest Directors, Tati made by far the fewest films of any name on that list. But what films they were.

Descended from Russian nobility, Tati was born Jacques Tatischeff in France in 1907, and grew up in comfort. His father owned a thriving, high-end framing business, and ultimately expected his only son to take over.

After military service, Jacques moved to London for an internship and discovered rugby. The sport became an outlet for his natural athleticism and inspired his nascent comic gifts. Tati discovered he had an uncanny knack for imitating sporting movements in a slightly exaggerated way, cracking up his fellow players.

In the early thirties, Jacques did something totally counterintuitive, abandoning any idea of following in his father’s footsteps to pursue a risky career as a comic actor on the stage. He developed an act called “Impressions Sportives,” which built off the highly physical mimes of athletes he’d improvised for his friends.

Soon enough, he was gaining notice on the music hall circuit and also honing his unique gift in a series of short films. Tati was briefly conscripted back in the Army when war broke out in 1939, but returned to his increasingly steady cabaret work when the Armistice between France and Germany was signed in 1940.

After conceiving a daughter, Helga, with dancer Herta Schiel in 1942, Tati broke off that relationship and returned to Paris, where, in 1944, he married Micheline Winter. That marriage would endure and produce two children, Sophie and Pierre, both of whom would end up working in the film industry.

The following year, director Claude Autant-Lara cast him in his romantic fantasy, “Sylvie et Le Fantome.” The experience made Tati decide to make his own films. He and producer Fred Orain founded a production company, and their first release was 1947’s “L’Ecole Des Facteurs” (“School for Postmen”), a short which had a positive reception.

Tati would then extend the premise of “Facteurs” to his first feature-length release, “Jour de Fete” (1949). Here Tati plays a postman in a small French village who tries to apply American methods to make his mail delivery more efficient. The delightful “Jour” was a hit with critics and public alike.

While most directors would seek to leverage their newfound success by cranking out another film quickly, Tati chose to take his time. He always believed that the high standard he set for himself could not be rushed. Eventually, his unyielding perfectionism would come back to bite him.

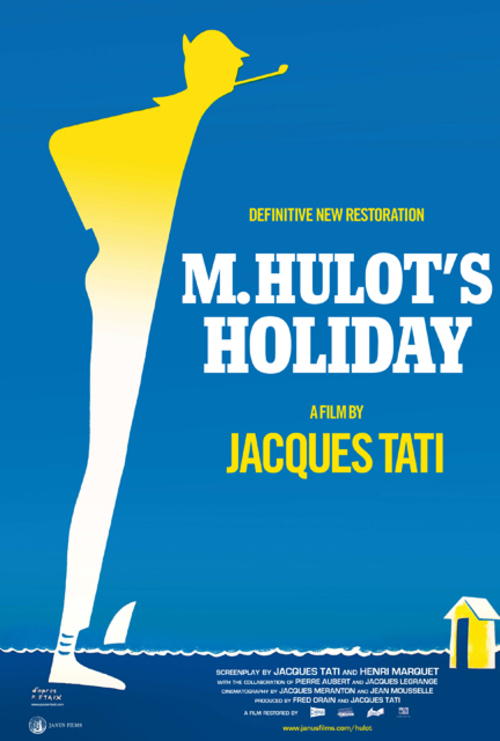

It would take four more years before the world witnessed the birth of Tati’s alter-ego Monsieur Hulot, but it was worth the wait. In “Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday” (1953), the title character, a gentle, befuddled fellow, gets in a series of scrapes and adventures while on a summer beach holiday. Tati satirizes French social and class conventions in depicting Hulot’s fellow vacationers.

In “Holiday,” the director’s flair for highly expressive physical comedy is even more in evidence. Hulot’s awkward gait and halting motions speak volumes about man’s ability to get lost or hamstrung in the big, confusing world he’s created. Without any need for dialogue, which Tati used sparingly as sound effects, our hearts go out to this endearing, quirky character.

Both critics and the public adored the film, which earned an Oscar nod for Best Original Screenplay. Tati was now breaking through internationally.

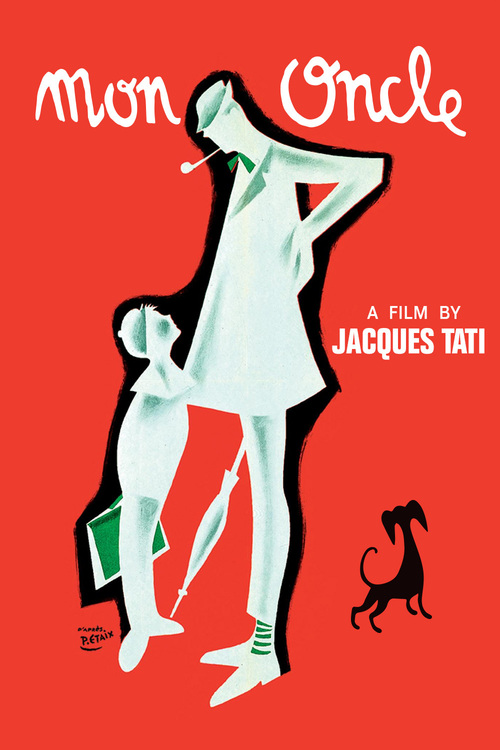

His follow-up came five years later with “Mon Oncle” (1958). This time, he shot in color, and set poor Hulot against all the mechanized gadgetry of contemporary life. Much of the action takes place at his sister’s home, equipped with all the modern conveniences, including a large fish-shaped fountain where water spurts from the mouth of the fish whenever company arrives. The infectious “Mon Oncle” would go on to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

Arriving in Los Angeles to attend the ceremony, Tati was asked by the Academy if they could offer him anything special during his visit. Tati wanted only to meet Stan Laurel, Buster Keaton, and silent film director Mack Sennett, and this was arranged. After their encounter, Keaton affirmed that Tati was carrying on the best traditions of silent comedy.

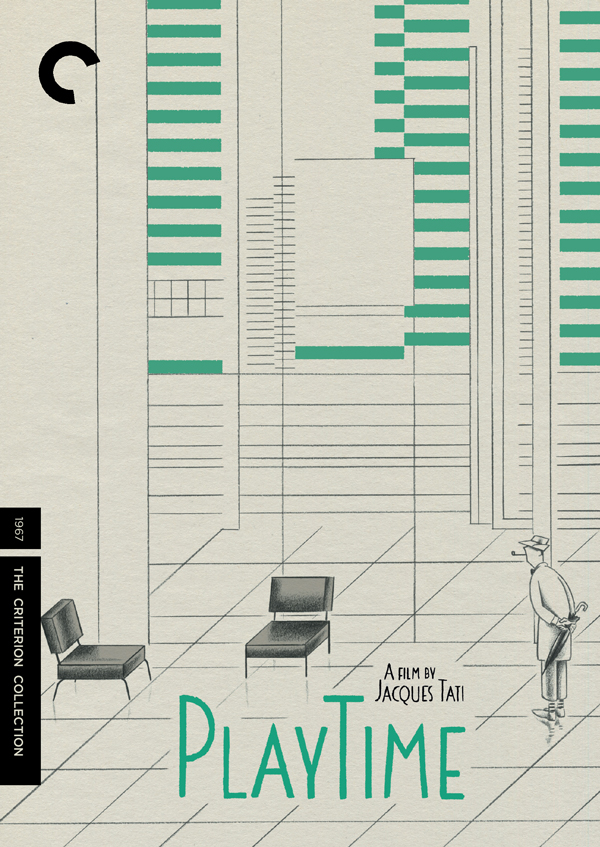

For his next release, Tati resolved to paint on a larger canvas. Whereas “Mon Oncle” had been set in a provincial town, his next project would be set in Paris. It would take on a bigger theme, lampooning our futile attempts to impose order on society through modern processes and technology.

The film, eventually called “Playtime” (1967), took a full six years to finish; the shooting alone extended three years. It would become the most expensive French film ever made up to that point.

Tati was insistent that “Playtime” be shot on expensive 70MM. film so that the action in both the foreground and background could be seen. Much as he eschewed dialogue, he also hated close-ups. He once said that he much preferred conveying human behavior through the legs than the eyes.

“Playtime” featured many expansive crowd scenes, and Tati personally choreographed every move with his actors, most of whom were non-professional. This took a lot of time, and the director never hesitated to shoot multiple takes.

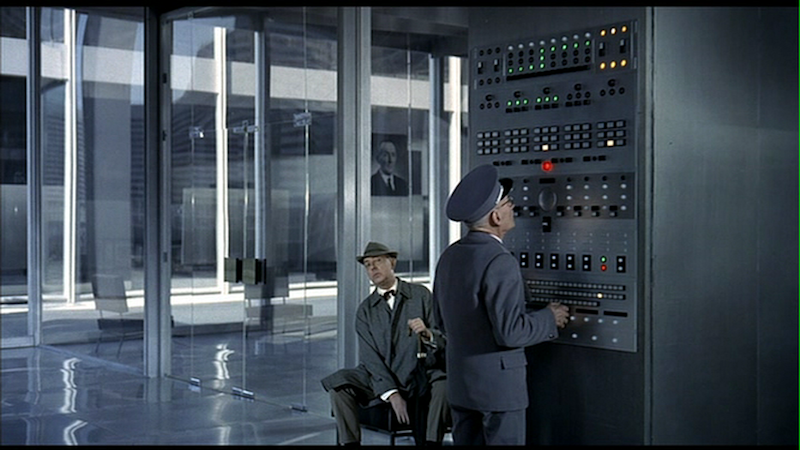

Perhaps his biggest challenge was how to portray a futuristic Paris. At first, Tati hoped to be able to film on location, with Orly Airport high on his list. However, he quickly realized that these public places could not be taken over long enough to capture all the intricate choreography he envisioned.

He then decided to lease land outside the city where the production built a city of its own, featuring one real building and several facades rendered in glass and steel. Once this elaborate set, dubbed “Tativille,” was erected a violent storm blew through and damaged it. This expense, combined with ongoing production delays, put Tati heavily in debt.

After all this, “Playtime” turned out to be a major commercial disappointment. Critics and historians have advanced various theories for its failure: first, there was less of Hulot in this film than in prior outings. Tati was tiring of playing the same character, and wanted instead to make a “film about everybody”. “Playtime” mainly focused on a bunch of American tourists exploring a rather cold, antiseptic Paris.

“Playtime” also had even less of a storyline than other Tati films; it felt more like a series of ingenious visual sequences flowing into each other. Finally, 1967 audiences found “Playtime” curiously dated, perhaps not surprising since it had been conceived a full six years before.

Due to the poor reception it received, “Playtime” was not even picked up for American distribution. The film would not be seen in the States for another five years. Making matters worse, Tati had refused to make any 35 MM. prints, so many smaller theaters could not have run the film even if they’d wanted to.

In the wake of this disaster, Tati filed for personal bankruptcy, and disbanded his production company. Most tragically, he would eventually lose the rights to all his films because of “Playtime,” ironically the title many today consider his masterpiece.

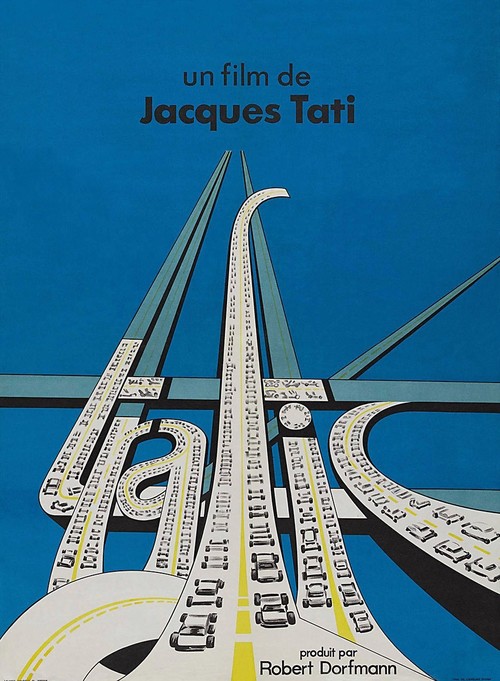

Still Tati was intent on rebounding. He set up a new production company and reprised Hulot once more in the modest but charming “Trafic” (1971). His last film would be 1974’s “Parade,” an undervalued work where Tati does his mime act alongside other circus performers.

Jacques Tati always took his time, but as the years progressed, time closed in on him. With several projects left unrealized, he died of a pulmonary embolism in November, 1982. He was 75.

Though Tati himself would never know it, his story had a happy ending. Several years after his death, his children Sophie and Pierre started working on regaining the rights to their father’s film legacy. They soon prevailed, and later Sophie led the charge in establishing “Les Films de Mon Oncle,” which served to protect and promote the Tati oeuvre. Thanks to all this work, a quick trip to Amazon allows you to purchase Criterion Collection’s comprehensive Tati set on Bluray.

In addition, our hero was reborn in Sylvain Chomet’s “The Illusionist” (2010). This animated film from the makers of “The Triplets of Belleville” was based on a never-produced Tati story; the title character is strikingly reminiscent of the director and his alter-ego. It is a loving tribute, well worth seeing.

On Tati’s death, one newspaper headline read: “Goodbye Monsieur Hulot. In death we cry, in life we did not help.” While that may be true, in the end his body of work survived. So wherever he is, Jacques Tati must be smiling, knowing that new generations of viewers can discover the enduring magic of his creation, Monsieur Hulot.

There’s no better time to start than now.