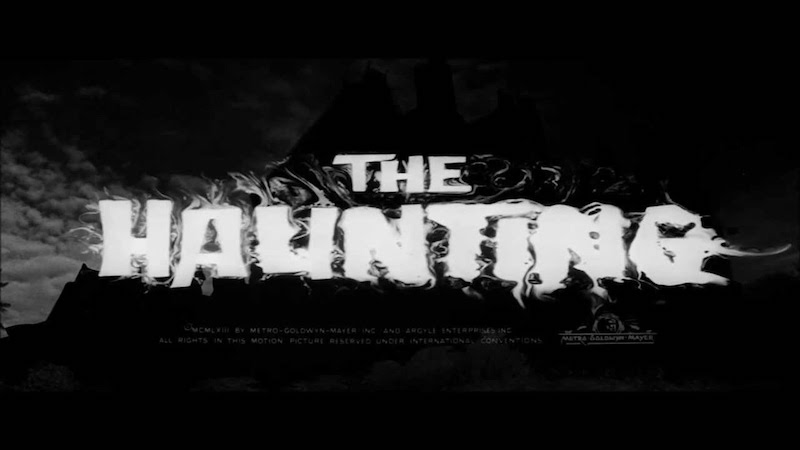

I first saw what I still consider the quintessential haunted house movie, Robert Wise’s “The Haunting,” when I was about 11.

Back then there was a weekly movie program on television called “Creature Features,” and through it my brother and I had quickly become aficionados of horror movies. Or so we thought.

We had consumed most of the Universal classics from the thirties and forties, and even shivered through 1959’s campy “House on Haunted Hill,” starring the ubiquitous Vincent Price. We thought we were ready for anything. We were not ready for “The Haunting.”

This eerie, shudder inducing exercise in psychological horror was in a whole different league from anything we’d seen up to that point. When it was over, we were both drained, shell shocked, traumatized.

Just how did this masterpiece of terror come to be? Well, it started innocently enough.

Veteran director Robert Wise had been hard at work completing “West Side Story” (1961) when he picked up Shirley Jackson’s new novel, “The Haunting of Hill House,” about a group of people who undergo a paranormal experiment by staying in a supposedly haunted house.

The story centers on one visitor in particular, Eleanor “Nell” Vance, a spinster approaching middle age whose emotional fragility makes her particularly vulnerable to the spirits occupying the house.

Wise found the book disturbing and saw a movie in it. He decided he wanted to make it as a tribute to his mentor Val Lewton, who’d produced 1944’s “Curse of the Cat People,” Wise’s first directorial effort. He contacted screenwriter Nelson Gidding, who had collaborated with him five years earlier on the the Oscar-winning “I Want to Live!”

Gidding read the book and initially advanced the intriguing theory that Nell was actually having a nervous breakdown and all the action was happening inside her own head.

When he met Jackson to discuss the screenplay, she told him this was not the case. Though she liked the idea of emphasizing Nell’s mental illness, she assured him that the supernatural occurrences were happening externally, to all the characters.

With that important detail straightened out, Wise cut a deal with the British arm of MGM to shoot the film in the U.K with a lean budget of $1.1 million. It would have to be a black-and-white production, which Wise intended anyway.

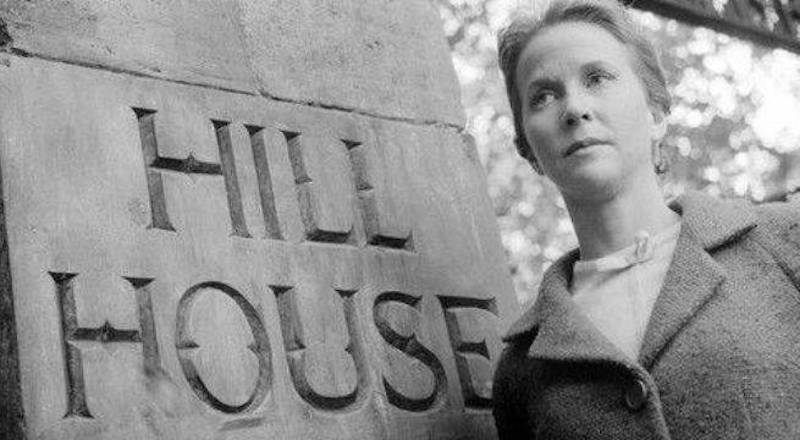

At this point in her career, Julie Harris was already fast becoming the First Lady of the American stage, specializing in complex, often vulnerable characters. Wise had seen her perform, and thought her perfect for Nell.

When approached, Harris readily accepted the part, since she found both the character and the subject of paranormal activity interesting. Wise had his Nell.

Claire Bloom was then tapped to play Theodora, the beautiful psychic who also happens to be a lesbian. Her fellow Brit Richard Johnson won the role of Dr. John Markway, the scientist overseeing the experiment who becomes Nell’s protector. Finally, Russ Tamblyn signed on as Luke, the nephew of the house’s current owner, who decides to tag along on this dubious expedition and soon regrets it. (Tamblyn had just worked with Wise playing Riff in “West Side Story”).

In keeping with the times, screenwriter Gidding had to portray Theo’s growing attraction to Nell subtly. The dark, impossibly sexy Bloom, outfitted in mod Mary Quant outfits, conveys it all with furtive, smoldering glances, along with a few instances of physical contact, including one memorable scene where she and Harris hold each other in bed as the ghosts pound on their door.

Wise knew the exterior shots of Hill House would be key to ratcheting up the tension about what might happen inside, and visited a number of old manor houses before settling on the imposing Ettington Park in Warwickshire.

To create the claustrophobic mood Wise wanted, the interior scenes would be shot on sets which included ceilings. (Traditionally most sets don’t have them).

Wise was not only a master editor, but a highly skilled cameraman. He recognized straight off that playing with odd angles, unusual panning and tracking shots and a constantly moving camera would accentuate the dread and sense of dislocation within the house.

Wise would later say this was among the most enjoyable films he ever made, partly because he got to experiment with shots and techniques he would never have considered for any standard drama.

Example: to make Eddington Park appear more ominous, he used infrared film which, in his words, “brought out the striations in the stone” and made it “more of a monster house.” Numerous other tricks and effects, both in and out of the camera, kept Wise and his team engaged.

For the actors, it was by most accounts a slightly awkward production. Julie Harris was experiencing a depression and felt cut off from the rest of the cast. They in turn were on their guard with her.

Ironically, her state of mind could only have helped her portray a woman who feels gradually isolated from her compatriots as the spirits in the house try to draw her away.

It may even be that there was some method (acting) to her madness, as after the shoot wrapped she and Claire Bloom quickly made up and became friends.

Still, Harris’s remoteness on set, combined with the bright lighting and heavy, ornate, rococo furniture featured in most every scene, made it a sober experience for the actors. On the plus side, everybody loved the director, who was unfailingly gracious, calm, but also very much in charge.

Wise knew that sound design would be critical to the film’s success. He had his technicians actually record creaks and noises in an old empty house which he then manipulated to maximum effect, adding in the tears, laughter and echoing, indistinct voices of the ghosts themselves.

Wise then played the pre-recorded sound effects on the set, so that the frightening noises we hear, the actors were also experiencing as the scenes were shot.

“The Haunting” was released in the fall of 1963, and initially received only mixed reviews. Some critics faulted the incoherence of the story, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times commenting acidly that the film “makes more goose pimples than sense.”

However, word-of-mouth confirmed what Wise already knew to be true: the movie worked. Audiences were petrified.

The film’s reputation has grown steadily over the years. Both Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese are huge fans, with Spielberg citing it as a “formative experience” and Scorsese rating it the scariest film of all time. “The Haunting” is also ranked number 13 on The Guardian’s list of top horror films of all time.

“The Haunting” was remade to lesser effect by Jan de Bont in 1999, with Lilli Taylor, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Liam Neeson in the Harris, Bloom and Johnson roles.

It was also reimagined as a Netflix series in 2018, reclaiming the title of Shirley Jackson’s original book. The reviews this time out have been extremely positive. Yet no matter how unnerved I become watching this newest iteration, it won’t seem quite as intense as the first time I saw the Robert Wise original.

Cowering in my bedroom at night with the bathroom light left on, I felt the fear of the unknown, that mysterious, unseen, malevolent force just behind the door. And I’m still scared, deliciously so, to this day.

Those of you casting about for ideal Halloween fare should definitely check out “The Haunting.” And by the way, if you’re planning to take your kids out trick-or-treating, steer clear of Hill House!