One of the more fascinating aspects of cinema history lies in identifying those films (and filmmakers) whose true quality and contribution only get recognized well after the fact. This is a somewhat rarer phenomenon than releases which are wildly popular in their time, but like a product cheaply made, corrode quickly as the years pass.

Falling decidedly into the former camp is the work of director Howard Hawks. Over a forty-plus year career, it’s astonishing that this brilliant director was Oscar-nominated only once. Sometimes the Academy gets it wrong. This was one of those times.

In his day, it was widely felt that Hawks was a solid craftsman and technician who know how to churn out entertaining, commercial pictures. He did not strive for the cinematic poetry the way his friend and colleague John Ford did. Yet of course, making an outstanding commercial movie is no less an accomplishment then crafting a great art film.

Probably Hawks’s own down-to-earth perspective on movies only reinforced this perception: he once said that good movies are made up of “…at least three good scenes and no bad ones.” He also defined a good director as “someone who doesn’t annoy you.” At first, these observations may sound flip and simplistic, until you begin to discern the wisdom behind them.

Hawks’s reticence was in keeping with his own view of himself as a man’s man — a man of action. In 1896, he was the first son born into an extremely wealthy family in the Midwest; his maternal grandfather, C.K. Howard, had founded the prosperous Goshen Milling Company in Wisconsin. Grandpa Howard doted on his eldest grandson, forgave his indifferent grades in school, and bought him a racing car and flying lessons to indulge Howard’s early (and lifelong) love for daredevil pursuits.

Howard’s family re-located to Southern California in 1910, and several years later, Howard was off to Cornell, where he’d end up graduating with a degree in mechanical engineering. On summer breaks from college, he was back with the family on the West Coast, and it was at this point that the quickly evolving, much ballyhooed movie business beckoned.

It was 1916. One day Hawks found himself racing his car against a young man named Victor Fleming who’d later direct two of the most famous films of all time in the same year, “Gone With The Wind” and “The Wizard Of Oz.” Fleming, seven years Howard’s senior, already had a job in pictures as a cinematographer. Starting as a prop boy, Hawks managed to impress no less a personage than Douglas Fairbanks on his handy set work, and Howard sensed he was on his way.

After serving stateside in the First World War, Hawks could not wait to get back to Hollywood. Over the next few years, the young man learned his craft, alternately writing, editing, and producing. He also initiated a wealth of contacts in the industry. (His family money came in handy when he floated a loan to Jack Warner!)

Howard wanted to direct, and his friend Irving Thalberg hired him as a story editor at MGM in 1924 with the promise that he’d let him helm a picture in a year’s time. When Thalberg eventually balked, Hawks quit and went to Fox.

There, he’d direct eight pictures over the next three years: six silents, and two “talkies.” It proved an excellent training ground, but by the end of this period, Hawks’s relations with the studio had soured. He exited again, still determined to make a bigger name for himself in the new phenomenon of talking pictures.

His opportunity came quickly. In 1930, another rich, prominent friend (and fellow aviator) named Howard Hughes asked him to direct a movie based on real-life gangster Al Capone. When finally released in 1932 after protracted wrangling with the censors, “Scarface: The Shame Of The Nation” was a monster hit. From that point on, Howard Hawks could sit securely in that director’s chair.

Looking at his best films, you can isolate two basic categories: his comedies, and his action/adventure pictures. In his best comedies, the female characters were usually front and center. In a pre-feminist age, these “Hawksian women” were every bit the match of their male counterparts, either dominating their men or foiling their attempts to finagle them into something.

Conversely, his more serious films often concerned male characters and camaraderie: men following a professional code of conduct for some greater good. Though often secondary, the female characters in these movies were usually able to keep up and play in a man’s world.

Beyond Hawks’s own magic touch, what all these outings share is a good script. Hawks once said revealingly: “I’m such a coward that unless I get a good writer, I don’t want to make a picture.” Of course, that’s not cowardice: it’s brains.

Also to his credit (and to the benefit of his films) was that in an age of studio control, Hawks stayed a free agent for most of his career. Still, this director was undervalued in the industry all those years he was doing his best work.

Finally, in Paris during the fifties, the young critics at “Cahiers Du Cinema” made the world wake up to the enduring significance of the Hawks legacy. These writers, many of whom became directors in their own right, saw the man’s genius, and proclaimed it. Then-in 1975, just two years before his death, Howard Hawks received an Honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement. Though it’s gratifying the Academy finally snapped to attention, the acknowledgement was way overdue.

Hawks’s work would go on to influence future generations of directors, including Robert Altman (who adopted Hawks’s technique of fast, overlapping dialogue) and Brian de Palma (who remade “Scarface” and dedicated it to Hawks and original screenwriter Ben Hecht).

The movies that follow constitute the very best of Howard Hawks. Even a cursory glance at these classic titles should reinforce the enormity of this man’s contribution to the medium he so loved.

Scarface: The Shame Of THE Nation (1932)

Paul Muni plays a brutal, ruthless gangster who rises to head the Chicago underworld. But thankfully, his descent is just as swift. Al Capone — and Prohibition — were still very much alive when this old chestnut was released.

Twentieth Century (1934)

John Barrymore is a washed-up Broadway producer desperate to get former leading lady Carole Lombard back into the fold. When he learns she’s on-board the Twentieth Century Limited with him, he sees his chance.

Bringing Up Baby (1938)

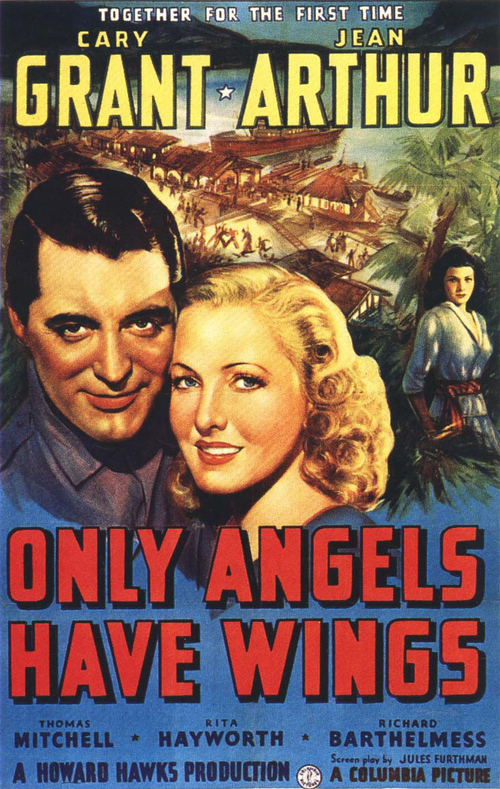

Cary Grant plays a nerdy paleontologist, Katharine Hepburn a daffy heiress saddled with a pet leopard. When she falls for him at first sight, his previously well-ordered life becomes one long mishap.

His Girl Friday (1940)

Cary’s back as a sneaky, ruthless editor who’s about to lose his best reporter (Rosalind Russell) to marriage. He uses every lowdown trick to foil her plans. She’s on to him, but still… does she really want to leave the newspaper biz?

Sergeant York (1941)

Gary Cooper portrays the real-life World War One soldier Alvin York, a simple country boy whose superb marksmanship and incredible daring made him a hero to millions back home. Coop got the Oscar for this.

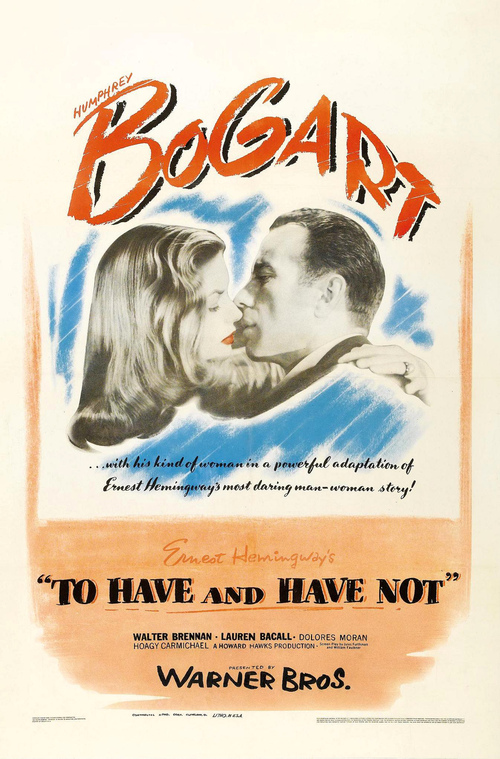

The Big Sleep (1946)

Bogie puts his indelible stamp on Raymond Chandler’s private eye character Philip Marlowe in this dense, twisty mystery. Lauren Bacall is the rich girl whose younger sister is mixed up with some highly unsavory characters.

Red River (1948)

John Wayne plays a tough, driven hombre who’s staking everything he has on an ambitious cattle drive north. He pushes eveyone mercilessly along the way, including adopted son Montogomery Clift, who finally rebels.

Rio Bravo (1959)

The Duke returns as a Sheriff holding the brother of a powerful bad guy in jail. As a large gang approaches to bust the brother out, Wayne’s got only three friends to rely on: a drunk, an old-timer and a kid. Will he still prevail?