As most of you know, I spend my life being picky about movies. There are just a few actors I’ll watch in almost anything. Jean Gabin makes that very short list.

Some reading this may have forgotten him, or never even heard of him. His heyday, after all, was nearly eighty years ago, and he’s been gone for over forty. Yet in his prime, no one could touch him. Gabin was France’s answer to Tracy, Bogart, and Cagney (take your pick), and he matched them all in sheer talent and charisma.

He was by far the most famous and revered French film actor before the Second World War intervened, as recognizable here as in his native France. Much later, after a career dry-spell, he found a way to reinvent himself and stay busy for the last twenty years of his life.

In 1904, he was born Jean-Alexis Moncorge just north of Paris, the last of seven children. His parents were both music hall entertainers. He showed his contrarian spirit early on by starting out as a laborer rather than entering show business.

Soon enough, young Jean changed his mind, and eventually managed to get a small part with the Folies Bergeres. In those early days, he would sing in the style of the wildly popular Maurice Chevalier.

Gabin made his film debut in 1928, just before the advent of talking pictures. Over the next few years, he would play supporting roles in over a dozen films, gradually gaining the notice of prominent producers and directors.

His first breakthrough came in 1934 when director Julien Duvivier tapped him for a now-forgotten film called “Marie Chapdelaine.” Later that year, Gabin found himself cast opposite Josephine Baker, the charismatic black performer who was the rage of Paris, in “Zouzou.”

Jean had wanted stardom all along, and hadn’t been shy about pursuing it. Reminiscing about his early career, he said: “I understood immediately that to get success I had to make for the front door, not for the back one. And the front door was the door of (early stage megastar) Mistinguett’s dressing room.”

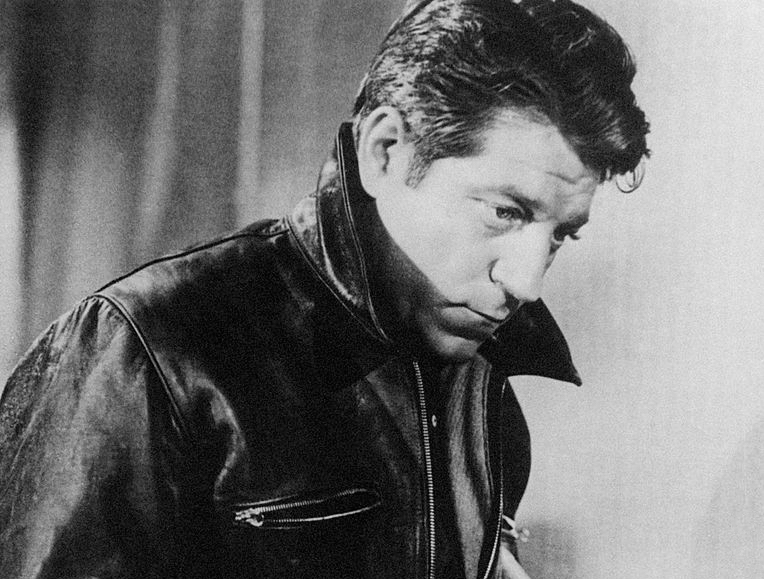

From the outset it was clear that this actor had a particular gift for film. Though not conventionally handsome, his face was enormously expressive and projected vulnerability beneath a surface toughness. Men respected him, and women adored him.

Gabin also understood the importance of underplaying to the camera, and excelled at it. One actress working with him commented on one big scene where she was making an impassioned speech, and Gabin was in the frame, just listening. Watching the rushes, she realized to her awe and frustration that all eyes would still be on him.

As of 1935, his rise seemed inexorable. First, Duvivier signed him up for two more pictures; the following year brought the actor’s first collaboration with Jean Renoir in “The Lower Depths.” Finally, in 1937, Duvivier and Renoir would cast Jean in two more films that would make him a star of the first rank.

In the first, Duvivier’s “Pepe Le Moko,” Gabin plays the title character, an elusive gentleman thief who hides out in Algiers’s impenetrable Casbah, and risks capture for the love of a noblewoman. “Pepe” cemented Gabin’s credentials as a romantic hero, while also inspiring the creation of Warner Brothers’ amorous skunk, Pepe Le Pew. In the second picture, Renoir’s “Grand Illusion,” Jean portrays an enlisted soldier captured by the Germans during World War One; this role established his macho, anti-hero, working class identity.

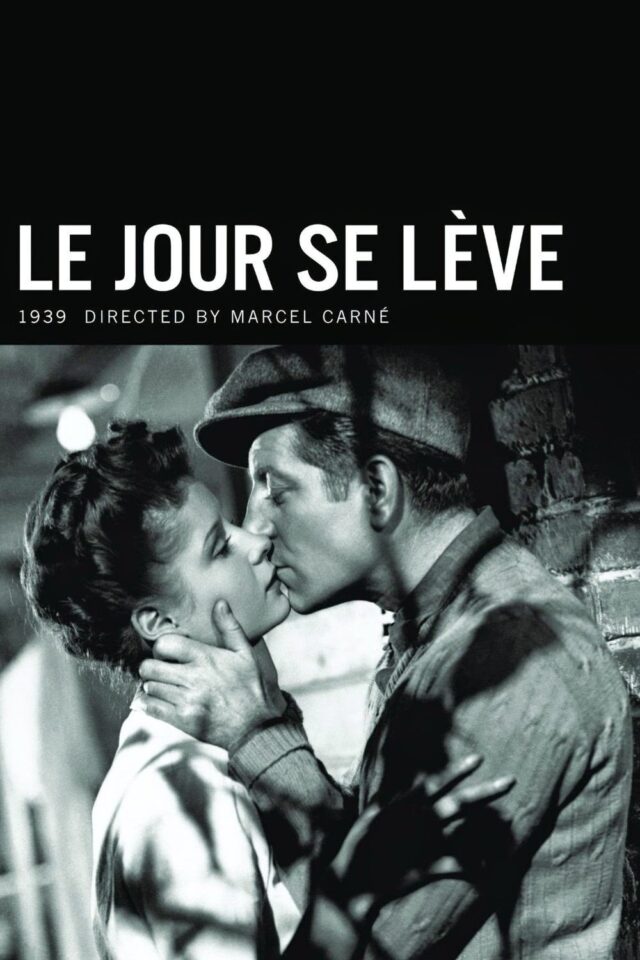

Gabin would add three more enduring classics to his filmography over the next two years: Marcel Carne’s “Quai de Brumes” (1938, a.k.a, “Port of Shadows”), Renoir’s “La Bête Humaine” (1938), and Carne’s “Le Jour Se Lève” (1939).

In 1940, the actor escaped the French Occupation by moving to Hollywood, where he hoped to build on his white-hot career streak. The industry saw dollar signs and gave him a hero’s welcome.

But all did not go as planned. Gabin disliked all the phony glamour of Tinseltown, and felt guilty about leaving his home and countrymen under the Nazi boot. Working at RKO, he gained a well-earned reputation for being demanding and difficult, and this did not serve him well when his first stateside release, “Moontide” (1942), failed at the box-office.

Both his directing mentors Duvivier and Renoir had also moved to Hollywood at this time, and like Gabin, neither found the inspiration to match their prior successes. Duvivier and Gabin would collaborate on 1944’s “The Impostor,” Gabin’s second American release, which also tanked.

Gabin’s saving grace over this difficult period was Marlene Dietrich. They had met by chance in New York soon after his arrival, and though both were technically married, sparks had flown. They began a six-year, on-and-off affair that extended through the war. Dietrich would later cite Gabin as the love of her life.

Jean had managed to alienate the RKO brass permanently when he refused to make a film he’d previously committed to unless Dietrich was cast opposite him. The studio ultimately fired him when he refused to back down. Gabin then decided it was time to get into the war.

He joined De Gaulle’s Free French Forces, and served with distinction in North Africa. The German-born Dietrich also enlisted on the Allied side, due to her anti-Fascist sentiments and a desire to be close to Jean. After the war ended, they were together for a time in Paris, but ultimately, Gabin was unwilling to leave his beloved hometown. He also wanted to get a divorce, remarry and start a family. When Dietrich wavered, he ended the relationship abruptly, breaking her heart.

In 1949, Gabin wed model Dominique Fournier, nearly fifteen years his junior, who also bore more than a passing resemblance to Marlene. Their union would endure, and produce three children.

Though settled domestically, Gabin’s film career had failed to reignite after the war. By all accounts, he continued to be challenging to work with. But now the success that had justified his mercurial personality eluded him.

Also, his appearance had changed during the war. His hair was gray, and he had put on weight. Jean was now middle-aged, and looked it. He could no longer play the romantic hero convincingly, and he seemed irrevocably linked to an earlier, bygone time.

Yet the intense drive that had first brought him fame did not desert him, and he was still every bit the actor he’d always been. He kept at it, performing in films and on-stage. He took the work he was offered.

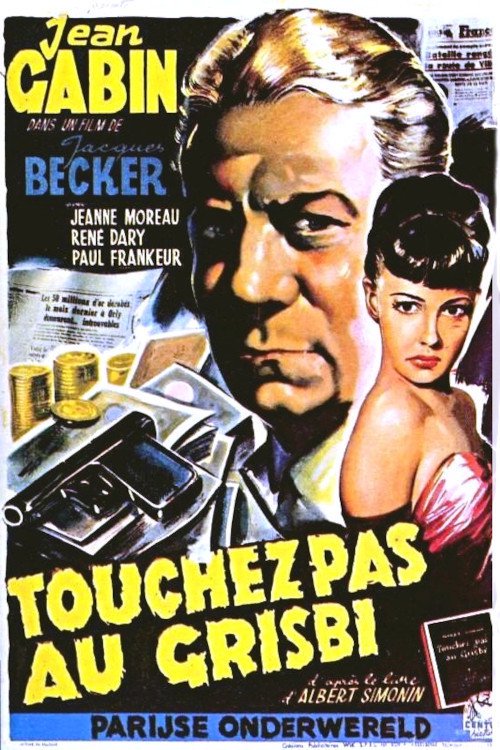

His comeback finally happened in 1954 with Jacques Becker’s “Touchez Pas Au Grisbi,” a superb, noir-tinged gangster film. Looking older and wiser, Jean scores as Max, a longtime master thief who lands in trouble when he attempts one final heist before retiring. The film holds up beautifully, and though it features a young Jeanne Moreau and Lino Ventura in his film debut, it is all Gabin’s show.

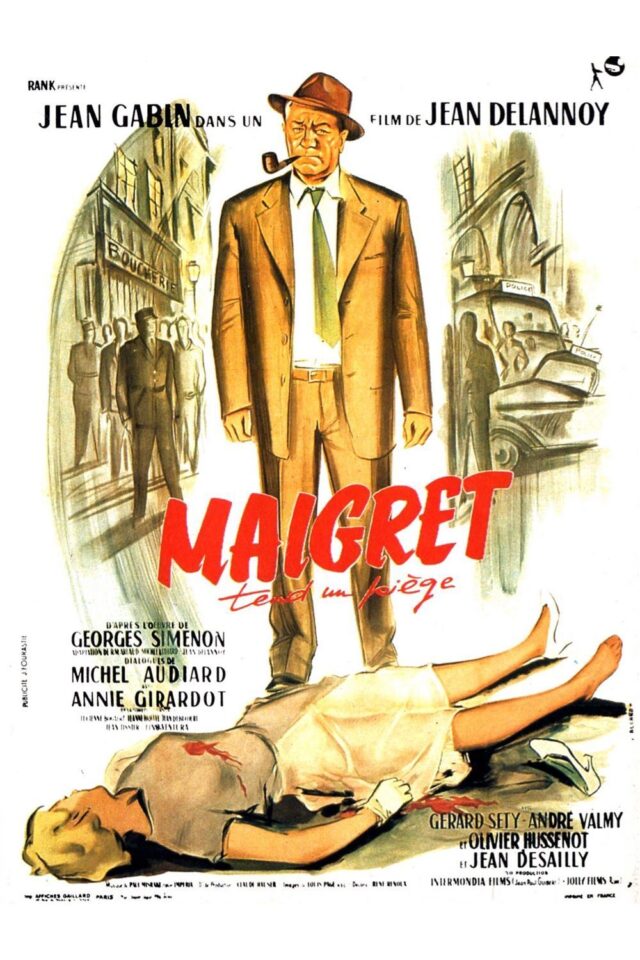

The actor would go on to play an assortment of aging crime bosses and weary policemen (notably Georges Simenon’s Inspector Maigret) over the next two decades. In the end, Gabin starred or appeared in a staggering 95 movies. Finally achieving financial security in these later years, he bought a farm in Normandy where he raised trotting horses and found a measure of peace between film projects.

Jean Gabin died of leukemia on November 15, 1976 in a hospital near Paris. He was 72. Though Gabin could be aloof, impatient and temperamental, his complex character and enormous talent clearly fueled his best performances and films. These we are deeply grateful for, and hold onto dearly.

Adieu, Lieutenant Marechal, Inspector Maigret, Pepe, Max and so many others. Adieu Jean Gabin.

More: Gallic Gangsters: Best French Crime Movies of the ’50s and ’60s