Why, one has to ask, is it not pure megalomania whenever directors direct themselves? Simply put, this is a breed of actor (and director) who understands the vision so completely that the need to control every element, even their own performances, overrides all doubt.

Of course, this could look quite a lot like megalomania, or it could simply be pure genius. Or perhaps a bit of both.

For many auteurs, it feels perfectly natural. Orson Welles started out with the Big Bang of “Citizen Kane,” his first feature film — with credits for directing, producing, co-writing, and starring — crafting what many critics agree is the best movie of all time.

Welles was no one-trick pony, and the list of films he directed and also starred in includes several of the form’s most enduring classics, such as “The Stranger,” “Lady From Shanghai” and “Touch of Evil.”

Other prolific practitioners are well known: chief among them Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Laurence Olivier, Woody Allen, Clint Eastwood and Kenneth Branagh. The signature on their films is distinct; the subjects fit perfectly with their directing styles, and the characters each of them play would be unimaginable in the hands of any other actor.

We still wonder who yells “Cut” at the end of each take, and what the meetings between leading man and director look like. Ponder that while you marvel at the incredible movies made by directors who direct themselves.

Movie: “Steamboat Bill Jr.” (1928)

Actor-Director: Buster Keaton

Role: William “Steamboat Bill” Canfield Jr.

Why It Works: If you had to come up with an unimpeachable rationale for directing and starring in your own movie, Buster Keaton’s ouevre would provide it. His films ran on the inventive, dangerous stunts he planned and executed so meticulously. Here, Keaton performs one of his most famous feats of precision timing, the “window stunt,” in which a façade falls on Bill Jr., the attic window perfectly centered as the building drops onto him. Keaton would make one more film before losing creative control for good.

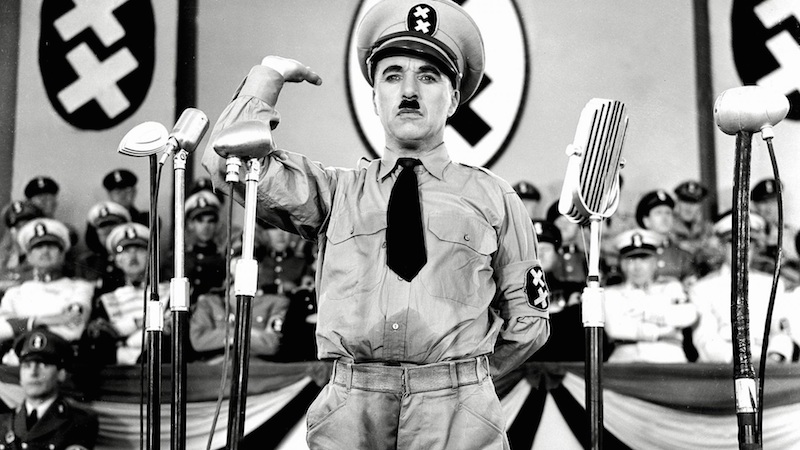

Movie: “The Great Dictator” (1940)

Actor/Director: Charlie Chaplin

Roles: “The Jewish Barber” and “Adenoid Hynkel”

Why It Works: Not only did Chaplin write, direct, produce and star in “The Great Dictator,” he actually plays two characters: the oppressor Hynkel and the oppressed barber. But wait, there’s more! All of this was undertaken for Chaplin’s first actual talkie, conceived at the late date of 1940. Later, Chaplin said that had he known the reality of the concentration camps, he would never have made the film. “The Great Dictator” is a satire for all time.

Movie: “The Stranger” (1946)

Actor/Director: Orson Welles

Roles: Nazi war criminal Franz Kindler; prep school instructor Professor Charles Rankin

Why It Works: As a Nazi fugitive hiding behind the persona of a small town academic, Welles makes a convincing split personality. Between his two acted roles, and those of star and director, there were actually four Orson Welleses on set. That’s a lot of auteur in one place, particularly if you’ve also got Edward G. Robinson on hand! Although John Huston was initially going to be hired as the director, producer Sam Spiegel let Welles direct on strict conditions, including the stipulation that any costs over budget would have to be paid out of Welles’ own pocket. Luckily, “The Stranger” was Welles’ biggest commercial hit.

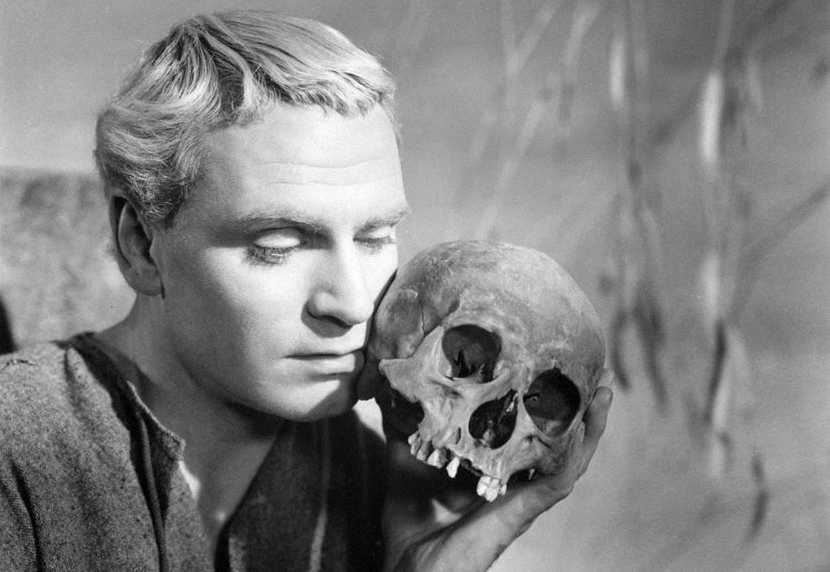

Movie: “Hamlet” (1948)

Actor-Director: Laurence Olivier

Role: Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

Why It Works: Olivier’s grasp of Shakespeare allowed him to make “whacking great” cuts to the original play that focused in on the psychological drama at the heart of the piece. It was the first time a leading man directed himself to a Best Actor Oscar, a record that held until 1998, when Roberto Begnini won for “Life Is Beautiful.” This was arguably Sir Larry’s greatest on-screen accomplishment.

Movie: “Sleeper” (1973)

Actor-Director: Woody Allen

Role: Miles Monroe, health food-store owner, jazz musician, and cryopreserved science experiment

Why It Works: In his fifth film, Allen merges his neurotic voice, incisive cultural commentary and slapstick comedy in an act of alchemy that he would find impossible to explain, let alone hand over to another director. Or actor. The movie’s sheer screwball inventiveness is often compared to that of Laurel and Hardy or Buster Keaton — high praise! But as it turned out, the movie won a Hugo Award for achievement in science fiction. Go figure.

Movie: “Henry V” (1989)

Actor-Director: Kenneth Branagh

Role: Henry V, King of England

Why It Works: Like Olivier, Branagh knows his Shakespeare well enough to edit, borrow from other plays, and make sixteenth century English understandable and accessible. Unlike Olivier, who also filmed “Henry V,” Branagh directed a movie with realism in mind (read: mud and blood vs. pristine sound stages), and stirred us into true brotherhood with his rousing “St. Crispin’s Day” speech. “We happy few,” indeed.

Movie: “The Unforgiven” (1992)

Actor-Director: Clint Eastwood

Role: Aging outlaw and paid killer, William Munny. He’s on one last job: to avenge a mutilated prostitute.

Why It Works: Eastwood’s last Western (to-date), “The Unforgiven,” pays tribute to his late directing mentors Don Siegel (“The Shootist”) and Sergio Leone. Eastwood sat on the project for nearly twenty years, waiting to be old enough to play the world-weary lead. The pay-off? Best Picture and Best Director Oscar wins, and a place on the United States National Film Registry for “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” movies.

Movie: “Fireworks” (1997)

Actor-Director: Takeshi Kitano

Role: Nishi, a violent and impulsive retired Japanese police detective, is facing a personal life crisis. He’s caring for his terminally ill wife, as well as nursing guilt over his partner’s paralysis. Nishi feels responsible since it happened on the job and he wasn’t there.

Why It Works: In the guise of a Japanese Charles Bronson, Kitano triumphs here both stylistically and emotionally, with his central character believably shifting between the extremes of brutality and tenderness. Kitano the Actor uses his face and body to convey the abrupt shifts in mood Kitano the Director was looking for.