This once-famous name may be unfamiliar to millennials, but even those with the remotest interest in film should discover him and his astounding body of work.

Among the top directors who have credited him as a direct influence on their work: Ingmar Bergman (who described him as “the best director in the world”), Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, Elia Kazan, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg.

Asked to name his three favorite directors, Orson Welles replied: “John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.” A neophyte director in Hollywood about to make his first film, Welles screened Ford’s “Stagecoach” repeatedly, then made “Citizen Kane.”

“I’m John Ford, and I make Westerns” was the simple, direct way he introduced himself at one famous meeting of the Directors’ Guild in the early fifties, where he stood up to the reactionary Cecil B. De Mille in condemning McCarthyism.

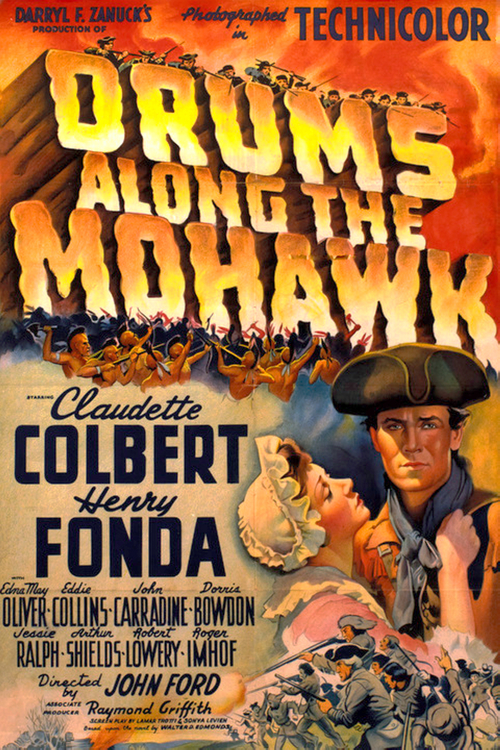

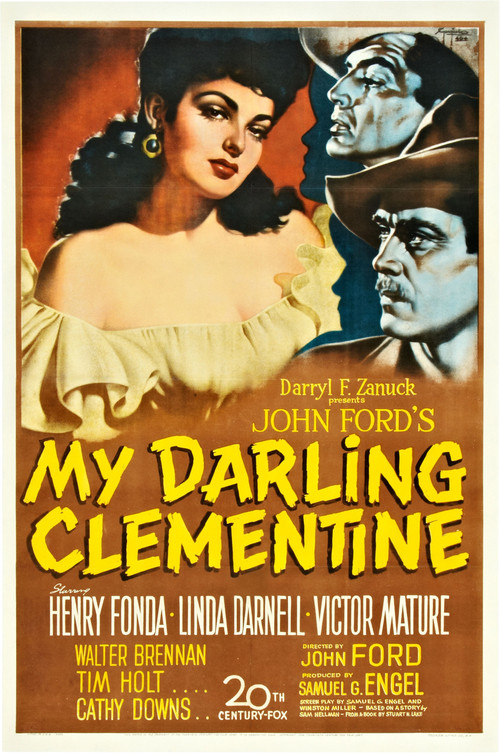

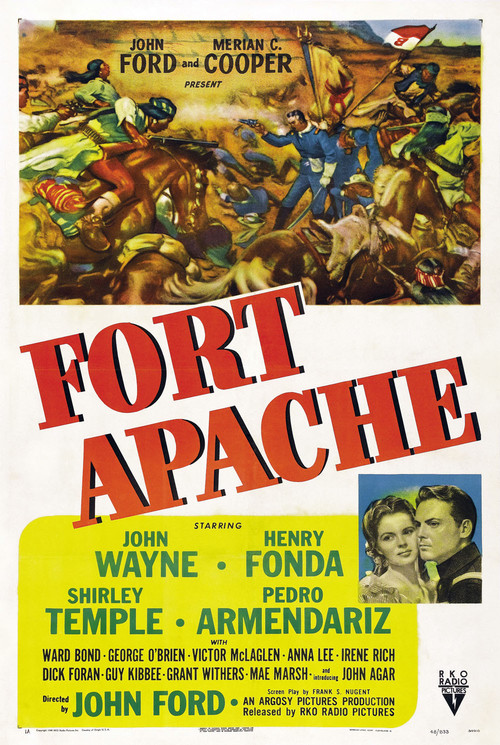

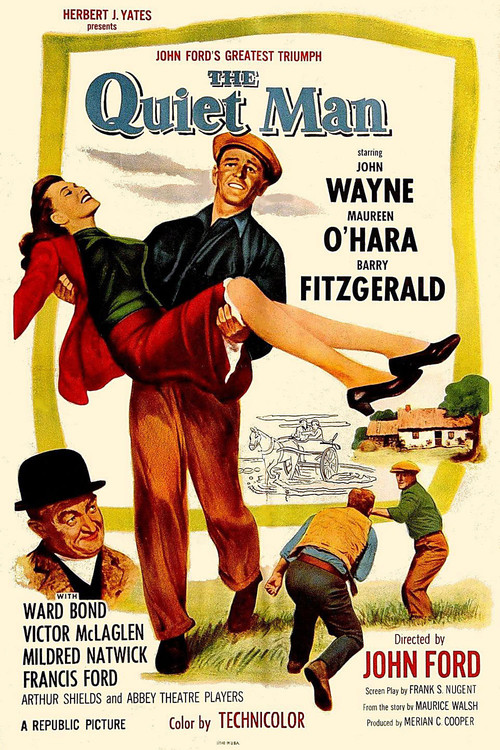

In fact, he did make Westerns, but a whole lot more. In fact, all his Oscars were for non-Westerns. The only Ford Western even nominated was 1939’s “Stagecoach,” the film that finally made John Wayne a star. Incredibly, the Ford film now considered by many the greatest Western of all time, “The Searchers” (1956), did not earn a single nomination. (Westerns, like comedies, were considered pure entertainment, not “serious” enough to warrant Oscar consideration).

Ford once said, “I like making movies but I don’t like talking about them.” Beyond reflecting his own enigmatic character, this may be why so many are unaware of his most notable achievements.

Though he rarely attended the Oscars, he still holds the record for Best Director wins; he took home four. Ford was also the first to win Best Director Oscars over two consecutive years, for 1940’s “The Grapes of Wrath,” and 1941’s “How Green Was My Valley.” (Joseph Mankiewicz would achieve the same distinction a decade later, for 1949’s “A Letter to Three Wives,” and the following year, “All About Eve”).

He was also one of the first directors to have more than one movie nominated for Best Picture in a single year. In 1940, both “The Grapes of Wrath” and “The Long Voyage Home” made the top list. Both lost out to Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rebecca,” the only Hitchcock film to win the top award.

Ford was particularly proud of the two additional Oscars he won for his documentary work during World War Two. Ford’s Naval service put him in harm’s way frequently. Filming one battle, he got a little too close to the action and was wounded in the arm by shrapnel. Later, General Eisenhower assigned him the delicate, difficult task of filming the liberation of the Nazi death camps. Eventually promoted to Commander in active service, he became a Rear Admiral in the Naval Reserve.

Throughout his career, Ford’s approach to filmmaking was highly distinctive: his movies celebrated the striving, pioneering spirit of America, and the key virtues that defined the national character: freedom, integrity, courage, perseverance. He gloried in our country’s majestic, untamed open spaces. He tended to prefer a stationary camera to a moving one, and long shots to close-ups. (Most Ford Westerns included at least one breathtaking sequence where processions of humanity were juxtaposed against rugged exteriors in Monument Valley). He always kept expository scenes and dialogue to a minimum. He was highly efficient, eschewing numerous takes. He tried to shoot just what he wanted to use, cutting “in the camera” to avoid others fiddling with his work in the editing room.

Actor Pat O’Brien captured Ford’s approach best: “John Ford, the old master, is the orderly type. Working for him is like being part of a ballet. He hardly ever moves the camera, but composes his shots like a master painter, a Rembrandt or Degas. The actor becomes part of the scene. Ford lets the action swirl past his lens. But the reality of his seamen, miners, dust-bowlers, horse soldiers, or western heroes, when he is at his best, is a literature that the screen rarely gets. Working for him one feels a special pride.”

Ford the man was a mass of contradictions: on set, he was autocratic and extremely tough on his actors, frequently humiliating them publicly. Yet he was also intensely loyal, building his own stock company of players and technicians who’d come back and endure his abuse time and again because they knew they were working with a genius and creating something special. A devout Catholic, he married a divorcee and frequently strayed. Sober and disciplined when making a film, he would often go on benders when production wrapped.

His terse tough-guy image also masked a sensitive interior he did all he could to hide. An oft-told story occurred during the Depression, when Ford was approached by an older, out-of-work actor who desperately needed money for his wife’s operation. Rather than show sympathy, Ford angrily turned on him and stalked off. Soon after, the man was surprised to receive an extremely generous check from Ford, who had also paid and arranged for a specialist to be flown in for the operation.

Ford’s older brother Francis explained it this way: “Any moment, if that old actor had kept talking, people would have realized what a softy Jack is. He couldn’t have stood through that sad story without breaking down. He’s built this whole legend of toughness around himself to protect his softness.”

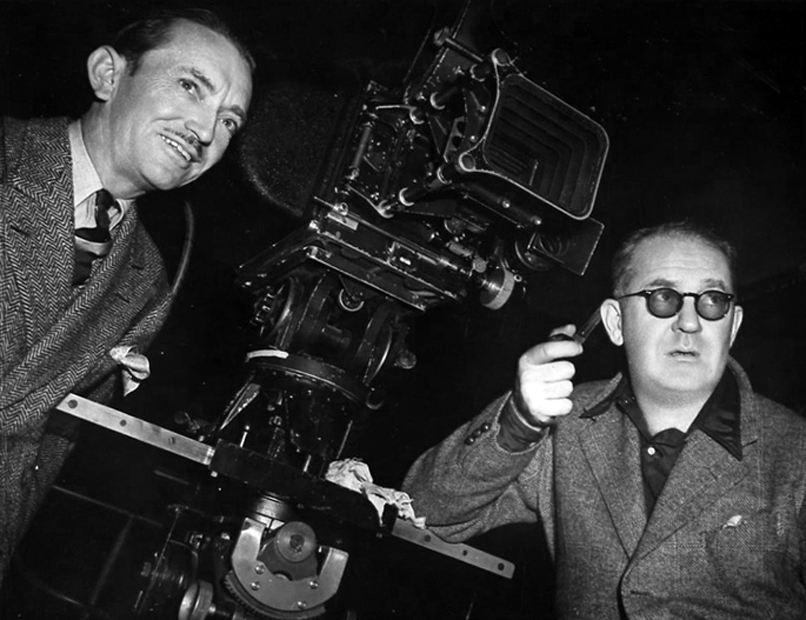

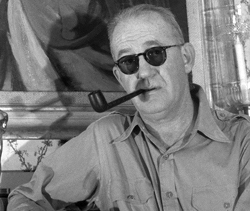

However, Jack Ford did let his humanity show through a variety of eccentricities: he would chew through handkerchiefs during takes, insisted on having music played on set, and always broke for tea in the afternoons. He wore dark glasses at all times, and later an eye patch. Though labeled a “man’s man,” he was priggish when it came to the use of bad language; particularly in front of a woman, this was a firing offense. As meticulous a craftsman as he was, he was notoriously untidy, and drove a beat-up old car.

The youngest of a family of six surviving children (five more had died in infancy), John Ford was born in 1894 to Irish immigrants who’d settled near Portland, Maine. His birth name was John Martin Feeney. In 1914, he decided to follow his older brother Francis to the promised land of Hollywood, where the burgeoning silent film industry was beginning to migrate at the time.

Francis, a dozen years Jack’s senior, was already making a name for himself as an actor and director. He hired his younger brother as an assistant, stuntman and occasional player. Within a couple of years, Jack was directing his own films. He did a series of highly successful Westerns starring Harry Carey, Sr. starting in 1917. Decades later, Carey’s son, Harry, Jr., would become part of Ford’s stock company.

By the time he broke through with the Western epic “The Iron Horse” (1924), he had changed his name from Jack to John Ford, and handily surpassed his older brother’s success in films. As the years went by and Ford’s success grew, he would cast Francis in a succession of small parts, often uncredited. True to the younger brother’s contradictory nature, this act seemed kind and cruel all at once.

As Ford entered his sixth decade in the business, it was increasingly clear his time had passed. His last great film, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” was released in 1962. After this, a combination of poor health and shifting public taste slowed him down considerably.

Fittingly, John Ford was the first recipient of the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1973. President Nixon attended the ceremony and bestowed the nation’s highest civilian honor on the ailing director, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Several months later, John Ford succumbed to stomach cancer at age 79.

John Wayne gave the eulogy at Ford’s funeral. The two men had always had a complicated relationship. Ford often ridiculed Wayne, once referring to him as a “big idiot.” He’d also never forgiven the flag-waving actor for ducking military service in World War Two.

Still, over the years, the director had come to respect Wayne’s talent and appreciate his unwavering loyalty. Over a quarter century, they had worked on 14 pictures together. Wayne fully recognized that Ford had made his career, and humbled himself accordingly in his presence.

Movingly, the Duke described his last visit with his mentor:

“I got word that he wanted to see me at his home in Palm Springs, and when I got there, he said, ‘Hi Duke, down for the death watch?’ ‘Hell no,’ I said, ‘you’ll bury us all.’ But he looked so weak. We used to be a triumvirate — Ford and me and a guy named Ward Bond. The day I went to Palm Springs, Ford said, ‘Duke, do you ever think of Ward?’ ‘All the time,’ I said. ‘Well, let’s have a drink to Ward,’ he said. So I got out the brandy, gave him a sip and took one for myself. ‘All right, Duke,” he said finally, ‘I think I’ll rest for a while.’ I went home, and that was Pappy Ford’s last day.”

Nearly half a century after his death, we’re still toasting the life and legacy of John Ford.