His name is seldom invoked today, but if you compiled any list of innovators who’d actually changed the shape of movies, it would have to include Saul Bass.

Bass transformed what opening credits sequences could mean and do for a film. Before World War II, a movie’s credits most always consisted of a studio logo followed by a series of title cards, all set to music. It was predictable and informational. Perhaps a period picture might earn some clever art design, but that’s about it.

Bass changed all that in the early fifties. He recognized that opening credits could do so much more than just list the names of cast and crew. Employing a range of techniques over time, he created a series of arresting designs and sequences that helped establish the mood and theme of the story to come. With Saul Bass on-board, a credits sequence became a distinctive, memorable element of any film.

As he himself described it: “My initial thoughts about what a title can do was to set mood and the prime underlying core of the film’s story, to express the story in some metaphorical way. I saw the title as a way of conditioning the audience, so that when the film actually began, viewers would already have an emotional resonance with it.” Way back when, this was a revolutionary idea.

Bass was born in the Bronx in 1920, and after high school, studied at Manhattan’s Arts Students League and Brooklyn College. He ended up in Hollywood designing print ads for movies like 1949’s “Champion.”

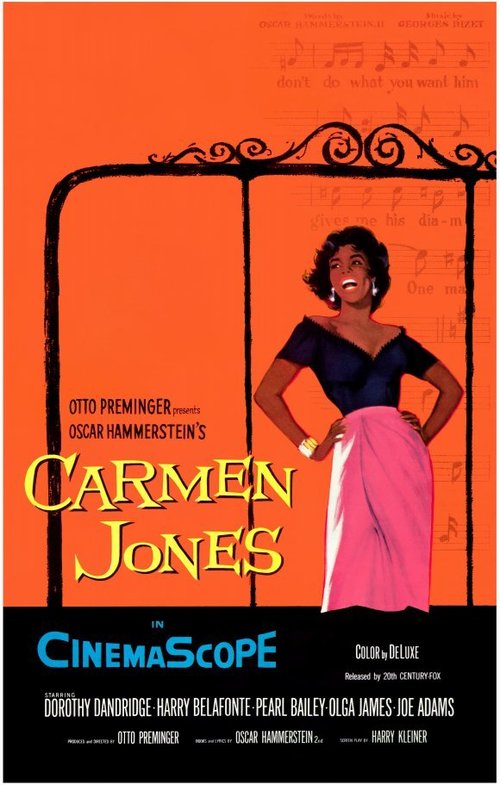

Bass first met director Otto Preminger in 1953, while working on a poster for Preminger’s ‘The Moon is Blue.” Preminger saw something in Bass, re-hiring him the following year for “Carmen Jones” and asking him to do not just the poster but the title sequence as well.

Next, Preminger had Bass conceive the opening sequence for his scorching film about drug addiction, “The Man with the Golden Arm” (1955). Its use of a fractured arm as metaphor for a broken man was both stark and powerful.

Seemingly overnight, Saul’s services were in demand. The artist would go on to work with such luminaries as Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Billy Wilder, and later Martin Scorsese.

His brilliant work for the Master on three particular films — “Vertigo,” “North by Northwest,” and “Psycho” — would be enough to guarantee Bass immortality, but he also played an integral role in conceiving what may be the most memorable Hitchcock sequence of all time — the shower scene in “Psycho.”

The director asked Saul to conceive every cut in this intricate sequence, and lay them all out on a storyboard. Though historians have debated how much credit he actually deserves for the final product, this terrifying moment of genius was certainly a collaborative effort.

Meanwhile, that same year, Stanley Kubrick not only had Bass design the titles for his epic “Spartacus,” but also conceive and choreograph the massive battle scene that is one of the film’s highlights.

By this time, Bass had a valued partner, both personally and professionally. In 1955, he had fortuitously hired Elaine Makatura, a talented young artist. Their successful business partnership soon turned romantic, and the two wed several years later. The union would endure and produce two sons.

In the late sixties, it appeared that Bass’s time had passed. “An increasing number of directors now sought to open their own films in ambitious ways rather than hire someone else to do it”, he explained. “Whatever the reasons, the result was ‘Fade Out.’ We did not worry about it: we had too many other interesting projects to get on with. Equally, because we still loved the process of making titles, we were happy to take it up again when asked. ‘Fade In’.”

Fortunately, as gifted graphic designers, Saul and Elaine Bass had another business to fall back on: creating corporate logos. Some of their major clients included AT&T, Continental, Kleenex, and General Foods. Their high-profile work in this field was even more lucrative than the movie sequences and posters they created.

The prolific duo also became filmmakers in their own right: first directing a series of short films, two of which were Oscar-nominated, and then one full-length feature, “Phase IV” (1974), which won critical praise but never caught on with the public.

In the mid-eighties, top directors like Scorsese, James L. Brooks and Penny Marshall, who’d grown up admiring the Bass’s work, decided they wanted to use them. Saul and Elaine were brought on to do the opening title sequences for such memorable pictures as “Broadcast News” (1987), “Big” (1988), and “The Age of Innocence” (1993).

Perhaps the finest work from their later period happens in “Goodfellas” (1990). No one who’s seen it will forget that instant when Ray Liotta slams down the trunk of the car as we hear his character, Henry Hill, proclaim in voiceover, “For as far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.” Then a freeze frame, and cue to Tony Bennett’s “Rags to Riches.” It sets up perfectly all we’re about to see.

“Goodfellas” author Nicholas Pileggi paid eloquent tribute to Saul and Elaine when he said: “You write a book of 300 to 400 pages and then you boil it down to a script of maybe 100 to 150 pages. Eventually you have the pleasure of seeing that the Basses have knocked you right out of the ballpark. They have boiled it down to four minutes flat.”

Soon after finishing work on Scorsese’s “Casino” (1995), Saul Bass succumbed to cancer at age 75, and the industry lost an authentic pioneer. Elaine, his beloved partner of forty years, survives him. Their legacy remains extremely influential, inspiring all the directors and designers who followed them.

We movie fans should also honor their contribution. Thank you, Saul and Elaine Bass, for giving us us so many great beginnings.