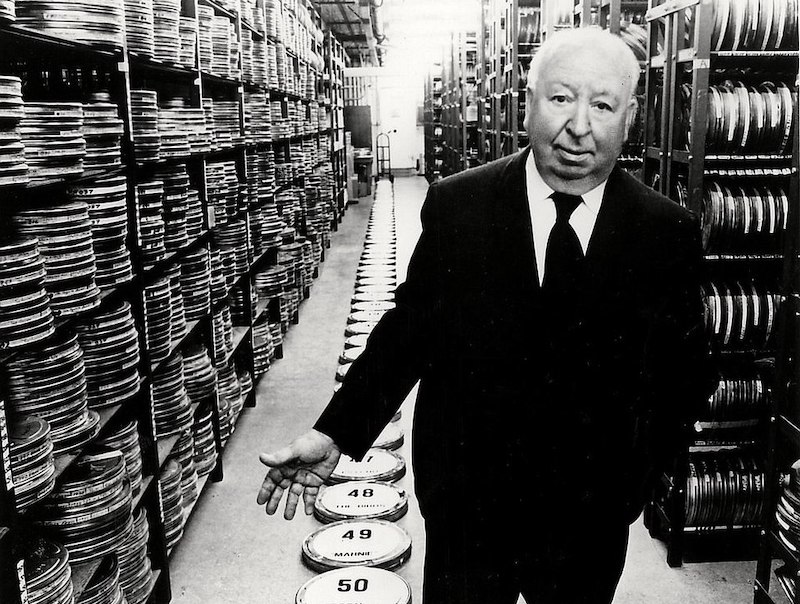

I think I can safely claim that Alfred Hitchcock’s name and work endure like no other director of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Today, many moviegoers in their teens and twenties may look blankly at you if you mention legendary helmers like John Ford, George Cukor, or Billy Wilder. Yet more than likely, they’ll know the name Hitchcock, and will have seen at least one of his pictures.

Along with five Oscar nominations for Best Director, he received numerous other awards over his long career, culminating in a 1980 knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II. And over three decades after his death, the accolades keep coming. As recently as 2012, Sight & Sound magazine’s critics’ poll named Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” (1958) the greatest movie of all time, toppling “Citizen Kane” (1941) from the number one spot. Not only do Hitchcock’s movies stay evergreen, they seem to get better with age. (Much as I admire “Vertigo,” my favorite Hitchcock outing is 1946’s “Notorious” starring Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant, the director’s favorite leading man. See it if you haven’t.)

Specializing in suspense, he spent his career figuring out more inventive ways to keep us unsettled, off-balance, and on the edge of our seats. Now and then he’d give us a comedy or a courtroom drama, but Hitch was at his most inspired when a character could be stabbed, strangled, or left dangling from a rooftop. “Fear isn’t so difficult to understand,” he once said. “After all, weren’t we all frightened as children? Nothing has changed since Little Red Riding Hood faced the big bad wolf. What frightens us today is exactly the same sort of thing that frightened us yesterday. It’s just a different wolf.”

Hitchcock himself received the biggest fright of his life in childhood, when after getting into some minor mischief, his father asked a policeman to lock five-year-old Alfred in a cell. The idea was to give the boy a taste of what it would feel like to be punished for a crime. Hitch’s dad, a London greengrocer, may not have won any “Father of The Year” awards, but he did manage to give his son a lifelong dread of the police. In fact, Hitchcock never drove a car for fear of being pulled over by the cops.

Hitchcock’s interests in drawing and photography led to his working in the U.K.’s growing film industry, where his first job was designing title cards for silent movies. He quickly climbed the ladder from assistant director to director. In 1926 he helmed “The Lodger,” a film widely acknowledged as the origin of the modern thriller. Hitchcock’s transition from silents to talkies led to such classics as “The 39 Steps” (1935) and “The Lady Vanishes” (1938). He was just getting started.

With the war in Europe underway, Hitchcock was lured to America by the famous independent producer David O. Selznick, who’d just finished a little movie called “Gone With The Wind.” For Selznick, he filmed “Rebecca” (1940), which won the Academy Award for Best Picture the same year as his underrated “Foreign Correspondent” was nominated. This double-whammy success convinced Hitchcock to stay stateside, where he flourished.

By the late 1940s, he’d grown tired of producers like Selznick offering their “suggestions,” so he began producing his own films. The Hitchcock style was already fully formed by then, including his habit of placing himself in funny cameos, and his way of stretching out the suspense until it was almost unbearable. As Hitchcock once put it, “There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it.”

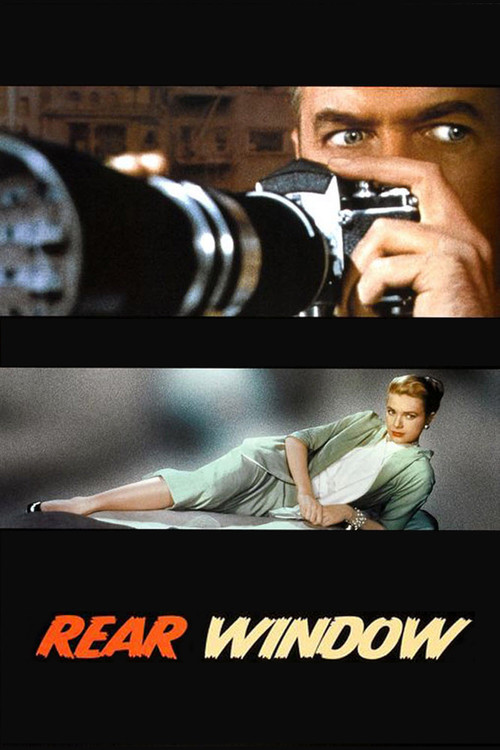

He also preferred actresses with a particular hair color, but not because they had more fun. “Blondes make the best victims,” he said. “They’re like virgin snow that shows up the bloody footprints.”

Gallows humor aside, Hitchcock’s movies included enough psychological undertones to satisfy Sigmund Freud, and enough visual style to influence a slew of contemporary directors from Martin Scorsese to Steven Spielberg. And Brian De Palma? He should pay royalties to Hitchcock’s family for the number of times he borrowed from “the Master.”

One reason Hitchcock continues to fascinate us is that he created scenes and set-pieces that stay in one’s mind like a nightmare. When you think of Hitchcock, you think of people being pushed out of moving trains, attacked by flocks of birds, stabbed to death in a shower, or hanging from Mount Rushmore. You don’t forget these moments. Ever.

Hitchcock was also that rare director who approached filmmaking as an art, pulling inspiration from German and French cinema, while at the same time making movies for the masses. “Some films are slices of life,” he acknowledged. “Mine are slices of cake.” Between the years 1954-1964, there was almost always a Hitchcock title among the year’s top-ten earners.

Hitchcock also knew how to change with the times. He embraced each new technology that came along, including the peculiar invention of television. Largely through TV (and those movie cameos), he became the first “on-air” celebrity director, whose face and form were instantly recognizable to the public.

But it wasn’t just emerging media that Hitchcock utilized to his benefit. As film censorship started loosening up in the sixties, Hitch took full advantage, turning up the dial on all the perversion and mayhem. By the time he released “Frenzy” (1972), a grim film about a rapist-murderer terrorizing London, Hitchcock was merrily creating some of the nastiest, most disturbing scenes of his entire filmography.

As for “Hitchcock the man,” biographers have spent decades depicting him as a complex, troubled individual who developed unhealthy obsessions with many of his leading ladies. He was also saddled with the reputation of disrespecting actors, an accusation he strongly denied.

Yes, he could be difficult, but what genius isn’t? The truth remains that Hitchcock inspired great loyalty and respect from many of his actors, including Cary Grant, James Stewart, and Grace Kelly. One must also consider that Hitchcock’s wife Alma, a film editor and screenwriter, remained at his side as a frequent collaborator for 53 years.

We feature nineteen Hitchcock films on our site. We believe they’re all great. We hope on the occasion of his birthday you’ll watch a few, and get reacquainted with his brilliance behind the camera. Even if you’ve seen most of these titles before, watch them again. Like most excellent movies, they benefit from repeat viewings.

Incredibly, Alfred Hitchcock never won a Best Director Oscar in competition, but the Academy eventually presented him with the Irving Thalberg Memorial Award in 1968. As if to pay back the snub, the man who had given us so many memorable quotes over the years responded with the shortest acceptance speech on record — a simple “Thank you.”

No, Hitch. Thank you!

For More: Hitch, “Lifeboat,” and the Actress Who Wouldn’t Wear Panties