Ever since I first saw “The Awful Truth” on New Years’ Day, 1985 at New York’s Cinema Village Theater, I have been a vocal champion of this timeless screwball classic from 1937. Even with a crushing hangover, my (then-future) wife and I were convulsed, and I knew I had found a film I would return to for the rest of my life.

I asked myself then why I hadn’t seen it sooner, and in the three decades since, have often wondered why this title is not as well-known as two later Cary Grant entries, 1940’s “The Philadelphia Story” and “His Girl Friday.” In my estimation, “Truth” is every bit as good.

Now that the esteemed Criterion Collection has released a blu-ray of this gem, those of you trying to remember if you’ve seen “The Awful Truth” should go out and buy it posthaste.

“Truth” is among our best tales of “re-marriage,” whereby a husband and wife who’ve split but truly belong together end up that way after much intrigue and hilarity. (Both the “Philadelphia Story” and “His Girl Friday” fall into this category as well).

Here the affluent Jerry and Lucy Warriner (Cary and Irene Dunne) drift apart, decide to separate, then spend the rest of the movie trying to subvert each other’s plans for a new life. All the while, we have little doubt as to the eventual outcome; these two misguided souls are clearly meant for each other.

In addition to her suave, handsome voice coach (Alexander D’Arcy) who initially raises Jerry’s suspicions, Lucy brings another man into her life, Dan Leeson (Ralph Bellamy), a rich Oklahoma oilman who lives just next door with his highly protective battle axe of a mother (Esther Dale). While gentle and good-natured, Dan is also the consummate rube, and Jerry delights in subtly ridiculing him at every turn.

Later, Jerry falls for stiff, humorless socialite Barbara Vance (Molly Lamont), and in one of the film’s best scenes, Lucy gets her revenge, destroying his prospects by imitating Jerry’s louche sister at a formal Vance family dinner. (Jerry, of course, doesn’t even have a sister).

Amidst all the cutting dialogue and inspired set pieces, we have Mr. Smith, played by Skippy. Some may consider Lassie our greatest canine star, but my vote goes to Skippy, who also played Asta in “The Thin Man” (1934) and George in “Bringing Up Baby” (1938), yet another Cary screwball farce directed by Howard Hawks. This gifted wire-haired terrier steals every scene he’s in.

Beyond its brilliance as a romantic comedy, “Truth” is widely credited as the film that established Cary Grant’s witty, urbane, fast-talking image. Though it would sustain the actor’s career over three more decades, it was in fact completely manufactured, far from the reality of his own grim, impoverished upbringing as Archie Leach in Bristol, England.

Though Grant never acknowledged it, “Truth” director Leo McCarey claimed a lot of the star’s persona was modelled directly on him. Eight years Grant’s senior, by 1937 McCarey was already a Hollywood legend with an unmatched flair for comedy, having actually discovered Laurel and Hardy and directed the Marx Brothers’ most inspired film, “Duck Soup” (1933).

Grant respected McCarey’s position in the industry, and also admired the director’s natural wit and casual elegance. He also resembled the darkly handsome McCarey, and from their first meeting, began absorbing his style and mannerisms. Doubtless the Cary Grant character we all loved was a composite of several human beings, but more than likely a big chunk of it was shaped by Leo McCarey on this production.

Grant was not yet a full-fledged star when he began this picture, but he was on the cusp. He was actually second-billed to Irene Dunne, a more established name and six years his senior. This awareness made him particularly nervous about how the finished film would be received.

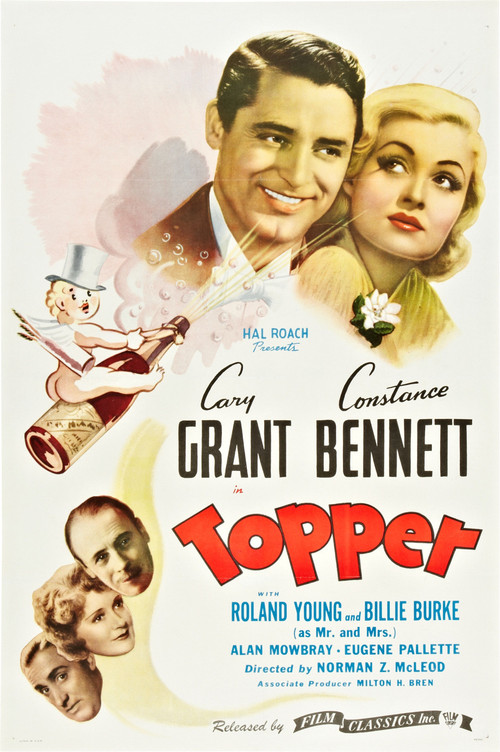

McCarey’s distinctive approach to filmmaking did little to soothe Cary’s anxiety. Harkening back to his early days doing silent film comedies for Hal Roach, McCarey was never married to a script. For him, words on paper simply served as a jumping off point for near-constant improvisation.

McCarey would often come on the set and first play the piano for inspiration. Then he’d get an idea and ask the actors to try out different bits of business that seemingly came out of nowhere. Grant reluctantly went with it, but became increasingly panicked as time passed. He had no clue what movie they were making, and sensed complete disaster.

Cary finally went to the studio bosses and begged to be taken off the picture. Failing that, he asked to switch roles with Bellamy so he’d have less screen time. Given a firm “no” for an answer, Grant returned to the set, resigned but still deeply apprehensive.

Of course he needn’t have worried. The wonder of “The Awful Truth” is that even with all that improvisation, the finished film is so beautifully constructed. There is not one scene that feels off or extraneous. It comes off as a meticulously choreographed comic ballet.

Credit also goes to co-star Irene Dunne, thoroughly winning on her own, and exuding genuine chemistry with Grant. She and Cary would make two more films together, neither as good: “My Favorite Wife” (1940) and “Penny Serenade” (1941).

And then there’s Ralph Bellamy. It’s both thankless and challenging to play the comic foil opposite Cary Grant, but Bellamy aced it, not once but twice — in “Truth,” and three years later, in the aforementioned “His Girl Friday,” playing Rosalind Russell’s clueless fiancé.

Both Dunne and Bellamy were Oscar-nominated for their performances here, though Grant was overlooked by the Academy, as he would be too often over the coming years. In addition, the film was nominated for Best Picture, Director, and Screenplay.

Only McCarey walked away with a statuette, but later stated rather sourly that he’d won it for the wrong movie. He had also directed “Make Way for Tomorrow” that same year, a superb but exceedingly sad drama about two elderly people who fall on hard times and are let down by their grown children. (“Make Way,” incidentally, became the basis for Yasujiro Ozu’s 1953 classic, “Tokyo Story”).

It’s striking that even the director of “The Awful Truth” would downplay the genius of his own creation. Today, this delightful, sophisticated romp remains beloved by buffs but still deserves a wider audience. So — to all those who somehow missed it, take some time out to enjoy the kind of sophisticated comedy they really don’t make anymore. At long last, see “The Awful Truth.”

More: 15 Rare Photos That Prove Cary Grant Was the King of Class