During the bleakest days of the Great Depression, screwball comedies gave struggling Americans vital relief and escape. These films skewered the upper class, which seemed only fitting, while simultaneously giving audiences the vicarious thrill of experiencing life on easy street, among high society.

These movies were script driven, propelled as much by rapid fire verbal interchange as pratfalls. They gave their audience credit for brains and taste. It was a different sort of comedy for a very different time.

High up on my personal list of top screwballs is Gregory La Cava’s sublime “My Man Godfrey” from 1936. Based on a novella called 1101 Park Ave, “Godfrey” contains more overt social commentary than most other films of its type.

Played by William Powell, the title character is a so-called “forgotten man,” a hobo found at the city dump by the Bullocks, a loony socialite family on a scavenger hunt. Impulsively, the family hires him to be the next in a long succession of butlers.

It’s soon evident that Godfrey is not who or what he seems. He’s a man wise beyond his years, who’s known hardship but also understands the corrosive effects of wealth since (we eventually discover) he’s from that world himself.

In his new role, Godfrey is more a keeper at an asylum than a butler, forced to treat his employees as children. And what children the Bullocks are, with the possible exception of the eternally frustrated patriarch, played by the rotund, gravelly voiced Eugene Pallette.

Alice Brady portrays his ditzy wife, who is equipped with a so-called protégé (Mischa Auer) with no assigned duties except to recite poetry on occasion and eat the family out of house and home.

The two Bullock daughters could not be more different: The conniving and entitled Cornelia (Gail Patrick) takes an instant dislike to Godfrey, while the flighty Irene (Carole Lombard) falls head over heels in love with him.

While at first Godfrey’s presence throws the whole family dynamic out of whack, in the end he will impart some valuable life lessons to the Bullocks — and to us all.

Hollywood veteran La Cava started out his career as an animator, working for Walter Lantz, creator of “Woody Woodpecker.” His career extended from silent days through the late 40s, and he would receive back to back Oscar nods for best director, for “Godfrey” and 1937’s “Stage Door.”

From the start, William Powell was La Cava’s choice for Godfrey, which meant that Universal Studios would have to borrow him from MGM. Best remembered for his role as Nick Charles in “The Thin Man” series, his witty, urbane quality made him ideal for the part.

For the key role of Irene, two names were floated at first: Constance Bennett and Miriam Hopkins. However, Powell insisted that his former wife Carole Lombard be cast instead. (The two had divorced amicably three years before).

Powell later explained that the chemistry between the more formal, grounded Godfrey and the daffy Irene was not unlike their own failed marriage. He knew there was no one else who could do Irene equal justice. He was right.

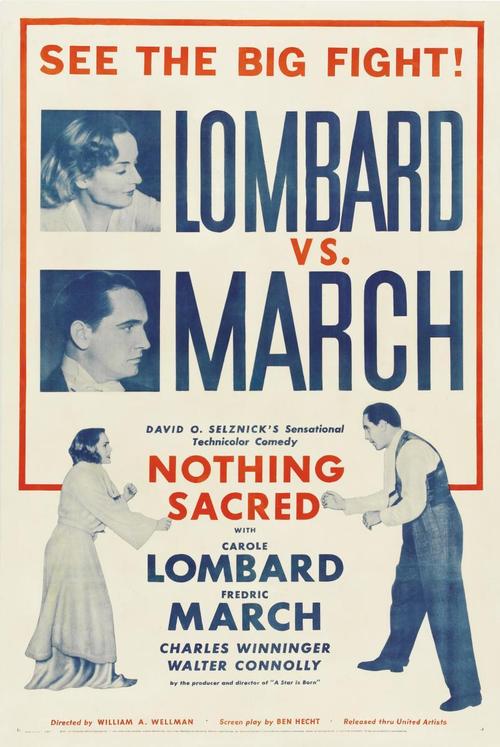

Of all the comediennes who graced the screwballs, none was more talented or captivating than Lombard. Two other movies prove it: 1934’s “Twentieth Century,” and 1942’s “To Be or Not To Be,” sadly her last film. Soon after, she died in a plane crash while selling war bonds. (Her second husband, Clark Gable, would never get over this tragedy).

Everybody in Hollywood loved Carole because she was incredibly funny and down-to-earth. Often she would unconsciously insert expletives when delivering her lines, forcing retakes. She always managed to break any tension on the set when this happened.

Overall, production went smoothly. However, early on La Cava and Powell had a difference of opinion over how Godfrey should be played, and after shooting one day they decided to resolve the issue over a bottle of scotch.

The next morning, La Cava arrived on the set and was handed a telegram from his star: “We may have found Godfrey last night, but we lost Powell. See you tomorrow.”

On release, “My Man Godfrey” was a big hit for Universal. Unfortunately its success came too late to prevent a major restructuring at the studio. Universal founder Carl Laemmle found himself out of a job after 25 years at the helm.

At the 1937 Academy Awards, “Godfrey” was nominated for six Oscars, including a richly deserved nod for Morrie Ryskind’s screenplay. It became the first film to receive four acting nominations, for Powell, Lombard, the wonderful Alice Brady as Mrs. Bullock, and Mischa Auer as protégé Carlo. (This was in fact the year supporting actor and actress categories were first introduced).

One Academy oversight lay in not citing the film’s stunning cinematography. As Roger Ebert put it: “God, but this film is beautiful. The cinematography by Ted Tetzlaff is a shimmering argument for everything I’ve ever tried to say in praise of black and white.”

Over eighty years after its release, “My Man Godfrey” still serves us — its audience — very, very well. Just watch it and see.

More: Gone Too Soon — Why the Sudden Death of Carole Lombard Still Hurts