As a kid, my favorite screen actor was Spencer Tracy. Like his close friend Bogart, the Ohio-born Tracy was not leading-man handsome, but became a star by projecting a unique and very human quality that viewers could readily access and admire: an everyman’s solidity masking an underlying sensitivity. He was known in Hollywood as the foremost “actor’s actor”— the player other actors measured themselves against. It’s easy to see why.

Tracy the man was a somewhat depressive, solitary human being, and a severe alcoholic whose binge drinking in the early days of his career was legendary. As a devout Catholic, he was consumed by self-loathing and guilt over the birth of a deaf son and his lapsed first marriage. Though linked to Katharine Hepburn for the last quarter century of his life, he would never actually divorce his first wife, Louise.

In real life, he could be gentle, kind, and amusing, but also cruel, remote, and impatient. He was a soul turned inward, largely unknowable. On-screen, he was something quite different: strong, familiar, reassuring, carrying his share of pain and loss with simple nobility. Though intensely serious about his craft, he made it all look so easy.

I never saw anyone with the same control and command of a scene. Today we’re accustomed to method acting, first practiced by Brando, Dean, and Clift, where technique is virtually invisible: rather than act, you become the part. By contrast, with Tracy you could see the technique, but it was executed with such mastery and subtlety that the effect was completely natural and seemingly spontaneous.

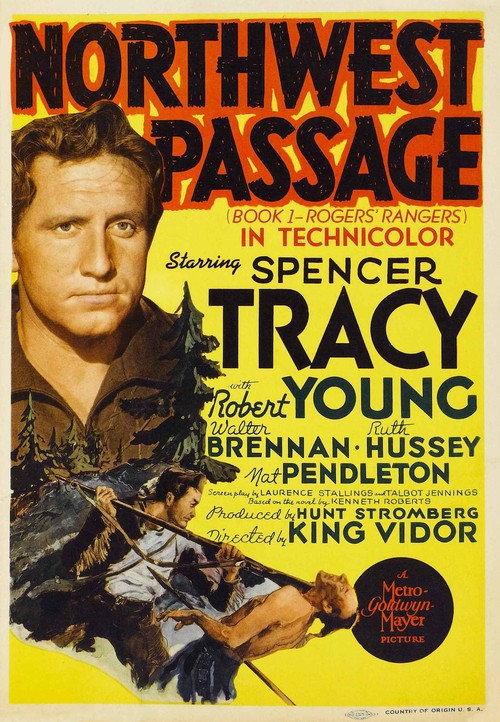

Some film historians claim that Tracy did his best work in the thirties, and two back-to-back “Best Actor” Oscars would seem to support this: first, for his portrayal of Portugese fisherman Manuel in “Captains Courageous” (1937), next for his stolid turn as Father Flanagan, a priest who uses tough love to save troubled kids, in “Boys’ Town” (1938). Though the latter film that hasn’t aged all that well, Tracy’s superb performance still shines through.

From that same period, Fritz Lang’s “Fury” (1936) shows the young Tracy at his most intense as the victim of small-town vigilante justice, transformed by rank injustice from good guy to a boiling cauldron of resentment. “Fury” remains potent viewing. That same year, he showed he could also play screwball comedy, rounding out an inspired foursome with fellow MGM players William Powell, Myrna Loy, and Jean Harlow in the delightful “Libeled Lady.” Tracy plays a frantic editor who hires Powell to save his paper from a ruinous libel suit. His professional problems cause him to leave his betrothed (Harlow) stranded at the altar-repeatedly! It’s inspired hilarity, all the way.

The forties, of course, would bring the first Tracy-Hepburn teaming (in George Stevens’ sublime “Woman Of The Year”), and with it one of the more fascinating and successful examples of on-screen chemistry. This unlikely pair, soon a couple in real life, would go on to make eight more pictures, some of them outstanding (in particular, 1949’s “Adam’s Rib”), all of them interesting just for their shared presence.

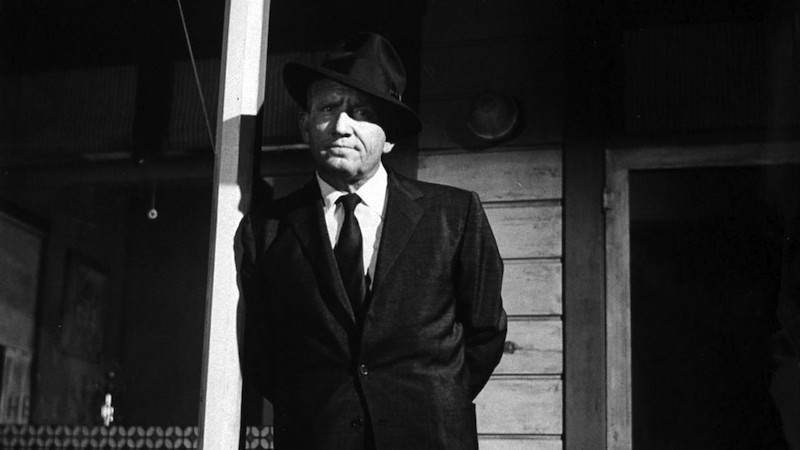

Three of my own favorite Tracy roles occurred later in his career, from the mid-fifties to early sixties. Tracy had lived hard and aged prematurely: he looked sixty at fifty, seventy at sixty. To my eye, the white hair, craggy lines, and cantankerousness only added gravitas to his already impressive authority.

John Sturges’ suspenseful “Bad Day At Black Rock” (1955) features the quintessential Tracy character: John J. Macreedy, a one-armed World War 2 veteran who arrives at a desolate western town to award a posthumous medal to the family of the young Japanese-American soldier who saved his life. His simple mission ends up exposing a nasty secret that some town citizens (Robert Ryan, Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine) want to stay buried. It becomes virtually one man against the whole town, but true to form, our hero hangs in there, even with just one arm.

Three years later, Tracy would portray Henry Drummond, a character based on famed lawyer Clarence Darrow, in “Inherit The Wind” (1958), a vivid dramatization of the landmark Scopes Monkey Trial of the 1920’s, in which a teacher was arrested for advancing Darwin’s theory of evolution in the classroom. Tracy’s deft performance is matched by Fredric March’s virtuoso turn as Matthew Brady (modeled on presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan). Just sit back, pretend you’re sitting in that humid courtroom, and watch these two old pros at work. (Also check out Gene Kelly in one of his only serious, non-dancing roles as a cynical journalist based on H.L. Mencken).

My final pick is Stanley Kramer’s long but brilliant “Judgment At Nuremberg” (1961), where this time Tracy presides over a courtroom, specifically the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals. The movie features Maximilian Schell as the impassioned prosecutor (the part netted him an Oscar), as well as two other players whose tragic characters would poignantly mirror the consuming sadness in their real lives: Montgomery Clift and Judy Garland.

Still, it is Tracy himself who towers over the film as Chief Judge Dan Haywood (inspired by Judge Robert Jackson, who presided at Nuremberg). In his weathered, strong face, we see America — and the freedoms it fought for — upheld and vindicated. Tracy’s closing speech is a stunner — well worth the wait.

After “Nuremberg”, Spence lived six more years in increasingly fragile health and died just after shooting his ninth and last film with Hepburn, Stanley Kramer’s “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner?”(1967), about a white couple whose daughter brings home a black fiancé (Sidney Poitier). Tracy was in such bad health, the studio wouldn’t insure him; Kramer risked everything he had to cast him. But it paid off: though his illness clearly shows, Tracy’s still the best thing in the picture, and his concluding speech where he weighs in on his daughter’s choice is for the ages.

Spencer Tracy may not be an enduring icon like Wayne or Bogart, nor was he a classic matinee idol like Gable or Grant. He was just a blocky, plain-speaking, forthright man of Irish descent, from America’s heartland…and also, just possibly the greatest screen actor of his day.