What it’s about

Shane (Ladd), a lone rider with a mysterious past, alights at the Starrett family homestead, where he meets Joe (Heflin), his wife Marion (Arthur) and son Joey (De Wilde). He offers to do manual labor for room and board. Though he wants to forget his violent past and be left alone, ultimately Shane must use the gun he'd foresworn to help Starrett repel a gang working for the ruthless Ryker (Meyer), who wants his land. When his underlings fail to dislodge Starrett, Ryker hires gunman Jack Wilson (Palance), and a final confrontation is at hand.

Why we love it

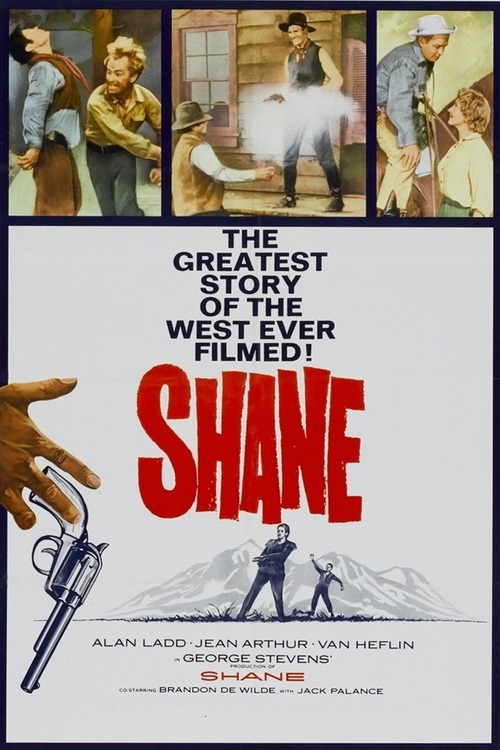

One of the finest Westerns ever made, George Stevens's “Shane” features a smart, lean script by A.B. Guthrie, Jr. that's by turns heartwarming and pulse-pounding, and stunning, Oscar-winning color cinematography by Loyal Griggs. Veteran helmer Stevens coaxes superb performances from the whole cast, particularly young De Wilde and a snake-like Palance. Note: this was Arthur's swan-song, and she's great as usual. Come back, Shane!