I’ve always loved Italy and most all things Italian: the country, the language, the food, and most of all, the people. I’ve always perceived the Italian national character as refreshingly open, romantic and passionate, with all human frailties and contradictions laid right out in the open. To me the Italians seem fabulously, enviably, alive.

Accurate or not, I’ve gained this perspective as much through watching Italian movies as through playing tourist. The great gift of international cinema is the exposure it provides to the rhythms and flavors of other cultures. Yet in experiencing those fascinating qualities which distinguish one nationality from another, we’re also reminded that ultimately we all confront the same challenges — at the very least, to survive; and if fortunate, to be happy and fulfilled, to love and be loved.

When most Americans think of classic Italian cinema, one name comes to mind: Fellini. From the mid-fifties on, Federico Fellini’s gift for visual poetry (executed on an increasingly grand, sometimes overblown scale) would elevate him to the status of acknowledged genius and world-wide icon for filmmaker as artist.

However, three older directors paved the way for him, and some of their early films, though markedly different in style and approach, easily equal the best of the younger man’s work. Their names are Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica, and Luchino Visconti. All three were born around the turn of the century, almost a full generation before Fellini, and each played a crucial part in reinventing their national cinema in the ashes of post-war Italy.

First, a priceless quote from a 1972 interview with de Sica where he recounts the birth of what became known as neo-realist film: “Do you know how was born the neo-realist style? After the war, we have no studio, no negative, nothing. And a newspaperman ask me: ‘What picture do you make? And I say: ‘I don’t know. Maybe the boys.’ Because I watch the boys on the street, the shoeshine boys. And they steal some money for a horse. And I look in Rome and find someone to give me money to make this picture. And I look at a man, a colleague of mine, Roberto Rossellini. And I sit on the steps and I ask Roberto, ‘What you do there?’ And he says: ‘A lady will maybe give me some money to make a picture about a priest in Rome during the liberation. And you Vittorio?’ And I say: ‘I don’t know, maybe about shoeshine.’ He says: ‘Ah, good luck.’”

This priceless memory of a seemingly casual conversation belies how pure creativity, born of dire circumstance and stripped of artifice, unwittingly created a revolutionary kind of film. With no money for sets, these directors shot on-location amidst the rubble of Rome, to a large extent without professional actors. Viewed today, the films are undeniably stark, without stylization or adornments of any kind. They feel very much like real life at its lowest ebb being captured on film. And the effect on audiences remains unusually potent.

Rossellini’s film “Open City” (1945) is my personal favorite. The story of a destitute pregnant woman and parish priest each struggling to survive in war-torn Rome during the Nazi occupation, the movie portrays the raw courage of the partisans who defy the Nazis’ oppression, risking certain death. Without the benefit of money, Rossellini creates a towering work that pays poignant tribute to the dignity of the human spirit when confronted with unthinkable cruelty and injustice.

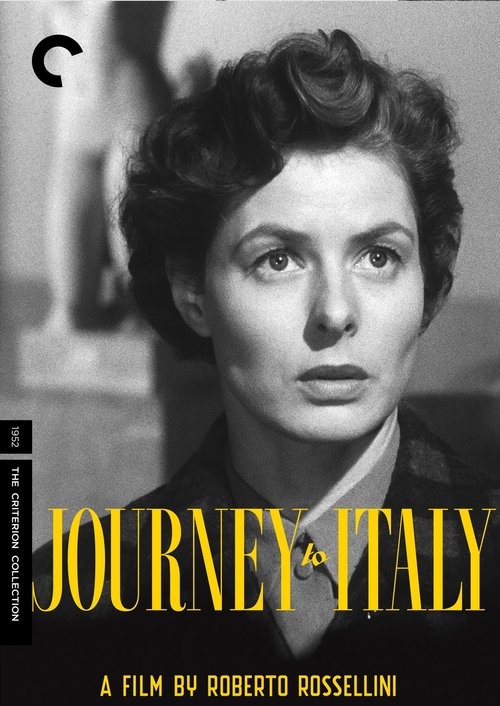

Over the next four years, Rossellini would complete his neo-realist trilogy — with “Open City” followed by “Paisan” (1946), and “Germany Year Zero” (1948). Both approximate but don’t quite equal the power of his first masterpiece. (Interestingly, a young man named Federico Fellini collaborated on the writing of the first two of these films).

Rossellini’s contemporary, De Sica, would also direct three early neo-realist classics: “Shoeshine” (1946), “Bicycle Thieves” (1948), and “Umberto D.” (1952). “Shoeshine” is an affecting first effort, but there’s a reason why “Bicycle Thieves” is undoubtedly the most famous of the three films; quite simply, this movie breaks your heart. A man who depends on his bicycle for his livelihood sees it stolen out from under him, and with his adoring and impressionable son in tow, scours Rome to retrieve it. Finally, at his wits’ end, he resorts to the theft of another bike to put bread on his table. “Thieves” speaks eloquently to the ultimate cruelty of grinding poverty, its heartless capacity to rob a poor man of the last thing he has to hold on to — his pride.

“Umberto D.” is every bit as powerful. The title character is an aging pensioner struggling to make ends meet in inflationary post-war Italy, who receives threats of eviction from his cold, uncaring landlady. Umberto can only rely on his one remaining friend, a small dog named Flike. What in less skillful hands could have been gooey melodrama becomes instead a wrenchingly honest tale about a forgotten, marginalized human being. “Umberto D.” remains a monumental achievement.

The final director we profile, Luchino Visconti, was a mass of contradictions. Born an aristocrat into one of Italy’s oldest families, as a young man he would become a communist. He’d move from his beginnings in film to directing in the opulent world of theatre and opera, then move back to motion pictures with lush, colorful period dramas that reflected a bold, sumptuous style and exacting sense of period.

Back in the forties, still under the nose of fascist censors, he directed “Ossessione” (1943), an unauthorized adaptation of James M. Cain’s “The Postman Always Rings Twice,” which would first be made in America just three years later. Often mistakenly referred to as the first neo-realist film, it is in fact more of a melodrama with earthy, sensual overtones. Still, “Ossessione” stacks up admirably to later versions of the story made stateside.

Visconti’s contribution to neo-realism actually comes down to one extraordinary film, made five years later: the Marxist-leaning “La Terra Trema,” about a family of fishermen in a Sicilian coastal village who dare to rebel against the ruthless wholesalers who give them a pittance for their back-breaking labor. Their brave efforts to go it alone backfire on them, and there are no happy endings. Incredibly (given the result), there was not one trained actor in the cast. The hard drudgery of the villagers’ lives is depicted in near-documentary style, with an effect that transcends traditional drama. Long but infinitely rewarding, “La Terra Trema” is must viewing for any serious film fan.

Rossellini, and in particular DeSica and Visconti, would all go on to do more films in the fifties and beyond, right alongside their gifted acolyte Fellini. Still, these early post-war films stand apart from everything that came after, purely for what they represent. At a sad and seminal juncture in Italy’s long history, its most talented filmmakers found the inspiration to record the moment for posterity with unflinching truth and tenderness. In doing so, they created cinematic art of the highest order.