Here’s a story of success plucked from adversity: the story of Hollywood’s response to the Great Depression.

The movie industry’s triumph in the 1930s lay in giving the public what it wanted to see. Its product was therapeutic diversion for millions of Americans who needed to get away from their troubles. By providing this crucial relief, American film reached a pinnacle of influence, at a time when most other industries were struggling mightily.

At the time of the 1929 crash, Hollywood was in transition: Sound was here to stay, but still in its early stages. There’d been huge investments made to convert shooting sets and theatres to sound. Movie careers had ended — and been launched — overnight. Hollywood urgently needed to recoup their conversion investment, and market this new form, even as the country faced unprecedented hardship. They had to catch up with their new technology fast, creating a cinema of sight and sound, images and words.

Fortunately the industry had some key advantages: first, their only big competition was radio (theatre, too, but it was more expensive). The studio system was also in place, so all the major players had stars, directors, writers and producers under contract; they even owned the theatres themselves. This created enormous efficiencies compared to today’s complicated, unwieldy system. The result: the studios were able to turn around product quickly and reasonably, and make it timely.

It was also relatively cheap to see a movie then – 10-25 cents. Hollywood’s strategy: for that dime or quarter, give the public more than ever. With every visit to the theatre, a viewer would get another plate for their plate set, and a string of entertainment: newsreels, cartoons, “B” pictures/serials, and “A” pictures.

For their “A” productions, the majors wanted intelligent stories, often literary adaptations, and glamorous stars, both to attract a desirable demographic and add prestige to the industry. The studios hired the best writers and actors from the Broadway stage. They then perfected a sophisticated marketing and publicity machine around these new stars. They programmed their lives, controlled and cultivated their images, tracked how they were doing with their public. And as a result, the movie business became one of the few to actually benefit from the depression.

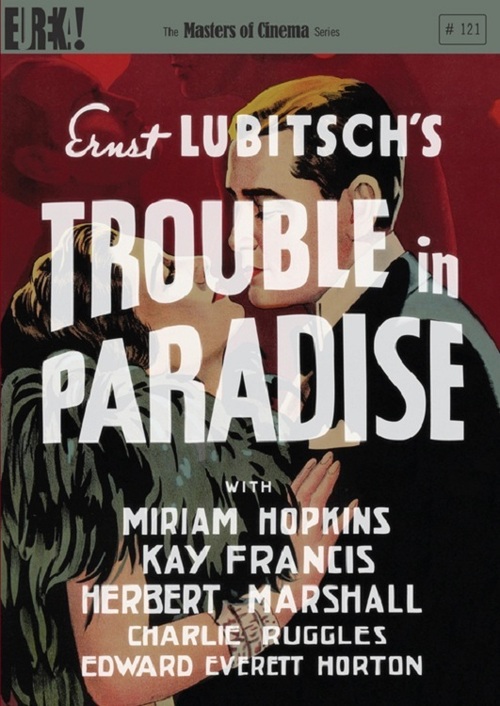

The “A” pictures of the day spanned a variety of genres, but it was the comedies and musicals that provided crucial escape for weary, impoverished audiences. There were several consistent threads in depression-era comedies: the public wanted to laugh at the rich, so characterizations were usually either stuffy or buffoonish, reflecting the populist sentiments of the New Deal. Still, it was the rich the public wanted to see portrayed. They enjoyed drinking in the rarefied atmosphere of the upper classes; it reassured them that real wealth still existed.

Like comedy, musicals were a natural for these viewers, especially as advances in sound technology allowed greater range of motion for the performers. No one made more of such advances than famed choreographer Busby Berkeley, who did, among other memorable pictures, “42nd Street” (1933).

Berkeley created immense, intricate set pieces featuring dozens of showgirls, shooting them from above and other unusual angles to achieve a kaleidoscopic, surreal effect. If you haven’t seen one of these, you’re missing out.

In 1932, Fred Astaire, a dancer who’d become a star on Broadway, came out to Hollywood for a screen test. The now famous verdict from his first audition: “Balding. Can’t act. Can’t sing. Can dance a little.”

Fred’s second film of 1933, “Flying Down to Rio” proved that assessment wrong, for it was here that he was first paired with Ginger Rogers. Though just supporting players, Fred and Ginger danced, and that was all the public saw or wanted to see. As one wag would later point out, he gave her class, and she gave him sex.

Not literally of course. In fact, Astaire’s exacting professionalism caused Ginger to suffer bloody ankles, and all too frequently, a bruised ego. She always had to fight the nagging suspicion that when they danced, all eyes were on him. So, they were cordial but never devoted friends off-screen.

Still their fame joined them at the hip, and over time, the duo would make a total of eleven movies together. Though the plots are wafer-thin, the dialogue is priceless, and the dance sequences incomparable.

Moving on to the comedic realm, the four Marx Brothers (Groucho, Chico, Harpo, and Zeppo) had already conquered vaudeville and Broadway when they made their first film, “The Cocoanuts,” in 1929. Their zany, anarchic humor was perfect for the time, since these inspired clowns were always ruffling the feathers of high society.

After a string of indelible comedies at Paramount, the brothers (sans Zeppo) moved to Hollywood’s most successful studio, MGM, in 1935, under the mentorship of Irving Thalberg. There they made two classics, “A Night at the Opera” (1935) and “A Day at the Races” (1937). After the latter film, with Thalberg dead of a heart attack at age 37, the Marxes lost direction and made only a few more films of lesser quality. Only Groucho remained in the spotlight with his game show, “You Bet Your Life,” first on radio, then TV.

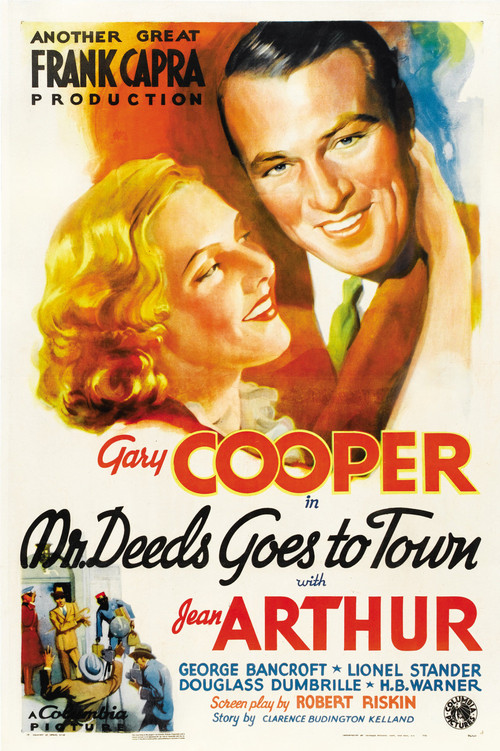

Now, we enter the madcap, magical world of screwball comedy. 1934’s “It Happened One Night” was made at Columbia, one of the lesser, Poverty Row studios, but its director was a young up-and-comer named Frank Capra.

Back then, studios used to loan out their stars for hefty fees, and MGM offered up Clark Gable to star in this one. Gable, whose career was on the rise, didn’t want to do it, but had no choice. If he refused, the studio could suspend him (stars had virtually no rights then). Happy ending: it turned out that Gable would win his only Oscar for this inspired comedy. In fact, “Happened” was the first film ever to sweep the Oscars in all major categories.

The film begins with heiress Claudette Colbert escaping the prospect of a loveless marriage, and traveling incognito around the country with little money. She meets reporter Gable on the road, who soon discovers her identity. Thinking he’ll hand his paper a big scoop, he reconsiders when he starts having feelings for her. After a few misunderstandings and missed opportunities, it all turns out right in the end.

“My Man Godfrey” from 1936 may be the screwball comedy with the most overt social message. Its star, William Powell, is one prominent example of an actor whose career was transformed by sound. In the silent era, he was mainly relegated to playing villains due to his slightly exotic look. When sound came in, his mellifluous speaking voice and urbane manner made him a leading man in his early forties.

In this picture, Powell plays Godfrey, a down and out “forgotten man” picked up at the city dump by daffy heiress Carole Lombard as part of a society ball scavenger hunt. It turns out this heiress is not only daffy, she’s daffy about Godfrey, and soon our beleaguered hero has become the butler for her wildly dysfunctional family, which includes an exasperated father, a dizzy mother, her shiftless protégé, and a cold, calculating sister, who can’t stand the new hired help. How will Godfrey, who is not precisely what he seems, parlay this odd situation into something that benefits all those other forgotten men living at the city dump? It’s a lot of fun finding out.

Today, not everyone realizes that urbane leading man Cary Grant actually built his career on screwball comedy. Under his original name, Archie Leach, he’d trained in his native England as a tumbler and acrobat, developing a flexible and fine-tuned physicality that would serve him well on-screen. 1937 was a pivotal year for him, as the public discovered his natural affinity for comedy in two enduring classics: “Topper” and “The Awful Truth.” Then, in 1938 Cary starred opposite Katharine Hepburn in director Howard Hawks’s “Bringing Up Baby” (which tanked on release but has since attained classic status).

Kate plays another flighty heiress, who meets handsome paleontologist Cary on a golf course and immediately falls for him. Unfortunately, she has a knack for causing accidents, and Cary becomes her latest victim. Through a ridiculous mishap, this earnest young scientist is forced to abandon a philanthropist named Peabody on the links, from whom he’s trying to extract a sizable research grant. This highly reasonable scientist never truly recovers his reason from that point on.

Cary would go on to do many more comedies (including another personal favorite, 1940’s “His Girl Friday“), as well as dramatic leads. He would make several suspense classics with Alfred Hitchcock, and alongside Bogart and Duke Wayne, become one of the top movie stars of his day.

Throughout the 1930s and right up to the Second World War, the movie business was at the peeak of its influence. That would only begin to change when the studios were forced to give up ownership of their theaters in 1948, which is also when that funny box started turning up as furniture in everyone’s living room, broadcasting a free new phenomenon called television. And thus began the gradual sunset of what is commonly known as Hollywood’s Golden Age.