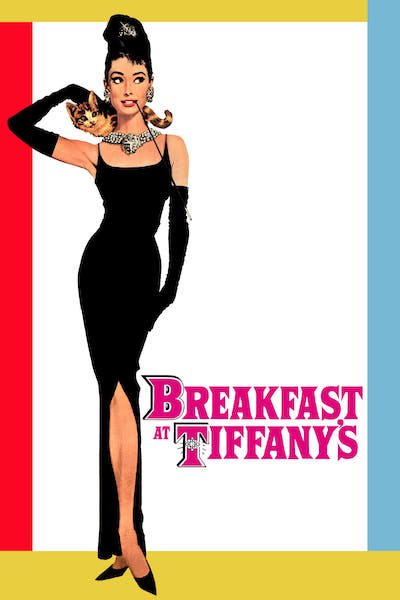

In an age when fewer young people exhibit interest or knowledge about classic films made before 1970, I am always amazed at the staying power of Audrey Hepburn, particularly among women.

In an age when fewer young people exhibit interest or knowledge about classic films made before 1970, I am always amazed at the staying power of Audrey Hepburn, particularly among women.

They discern in her qualities of grace, style, and class that are sadly of another age but still resonate today. She has become a sort of ideal for how a woman looks and behaves at her very best. If the antiquated term “chic” is ever uttered these days, chances are Hepburn’s name appears in the same sentence.

And the film most responsible for her exalted standing is undoubtedly 1961’s “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” When women in their twenties think of Hepburn, most often they picture Holly Golightly in her little black Givenchy dress.

When Hepburn first signed on, she could hardly have guessed that this would become her most iconic role. In fact, she approached the whole project with trepidation. As she described it, she felt she was an introvert being asked to play an extrovert for the first time.

Truman Capote had written the novella on which the film was based, and always envisioned Marilyn Monroe as Holly. After showing some initial interest, Monroe was convinced by her acting coach Lee Strasberg that playing a “party girl” would not be good for her career.

She decided to pass. So did Shirley MacLaine and Kim Novak. When Hepburn finally came on the scene, Capote was not happy, convinced she was totally wrong for the part.

He had a point. Hepburn’s image was virtually the opposite of Monroe’s. While Marilyn was a sexy, earthy working class girl you could believe came out of nowhere, the chronically slender Hepburn exuded a cultivated, patrician nobility. Could she actually play a glorified call girl transplanted to the big city from a tiny town in Texas?

Hepburn knew just how Capote felt about her, and his presence on set only made her more nervous, contributing to weight loss she didn’t need during production.

Production was not always smooth. For instance, the memorable opening scene with Hepburn gazing in Tiffany’s window was shot very early on a Sunday morning. Still, word of what was happening quickly spread, and crowd control became an issue.

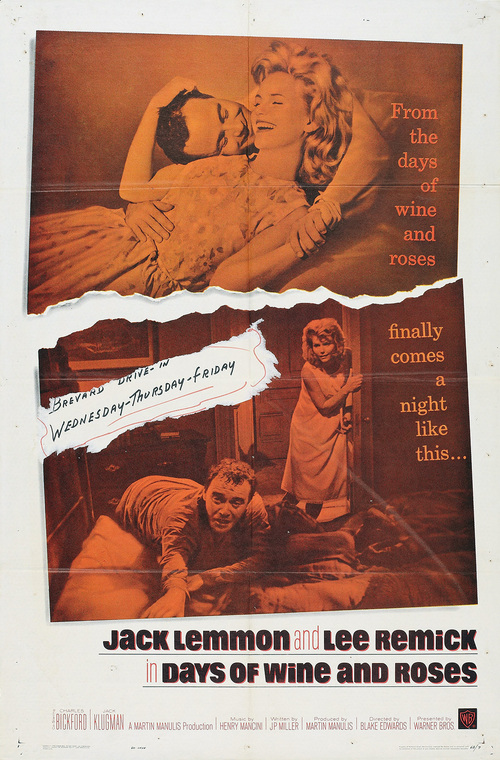

Unnerved by all the gawkers, Hepburn flubbed a few takes. Worse, the scene called on her to nibble on a pastry during the scene, and she hated pastries. She was well on her way to indigestion before director Blake Edwards finally got the shot.

However uneasy she may have been initially, underneath the dazzling smile and impeccable manners lay a steely determination. A thoroughgoing professional, Hepburn was going to do whatever it took to bring Holly Golightly to vibrant life. She knew that her performance would make or break the whole film.

By stretching herself in this part, Hepburn extended her range at just the right moment. The Audrey Hepburn of the fifties was a gamine — an exquisite, often shy young beauty. At the dawn of the sixties, “Breakfast” set her up for the more confident, human, and womanly roles she’d tackle over the remainder of her career.

Her approach was to make Holly an adorable but frustrating kook — an essentially lonely person, set adrift, who tells herself the key to happiness is discarding her old life, recreating herself, and finding a rich husband. True love is not even a consideration.

Enter Paul Varjak, a struggling writer and Holly’s new next door neighbor. What he and Holly share draws them together but also keeps them apart: a powerful emotional connection, and a shared poverty. Both of them are “kept” by other people. Paul is definitely not part of Holly’s plan.

Newcomer George Peppard was perfectly suited to play Paul. Throughout the film, he projects the serious, watchful, slightly restless quality of a novelist stuck in a situation that’s inhibiting his ability to work. He knows what he’s capable of, but he’s blocked.

It is the best thing Peppard would ever do on the big screen, and what few realize is that the part almost went to Steve McQueen, who, fortunately for George, was still committed to his TV series, “Wanted: Dead or Alive.”

Peppard and Hepburn got along, but the actor clashed with Blake Edwards and Patricia Neal, who plays Paul’s wealthy sponsor — and lover. Peppard was fanatical about his Method Acting training, which caused him to play scenes in line with his own understanding of the character. Simply put, he wouldn’t take direction. It hardly mattered in the end.

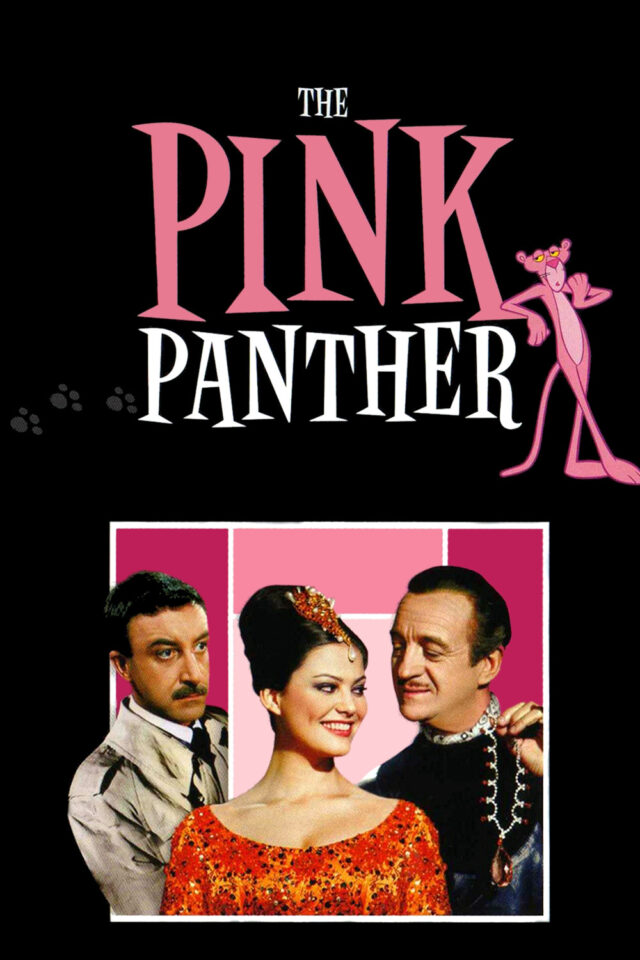

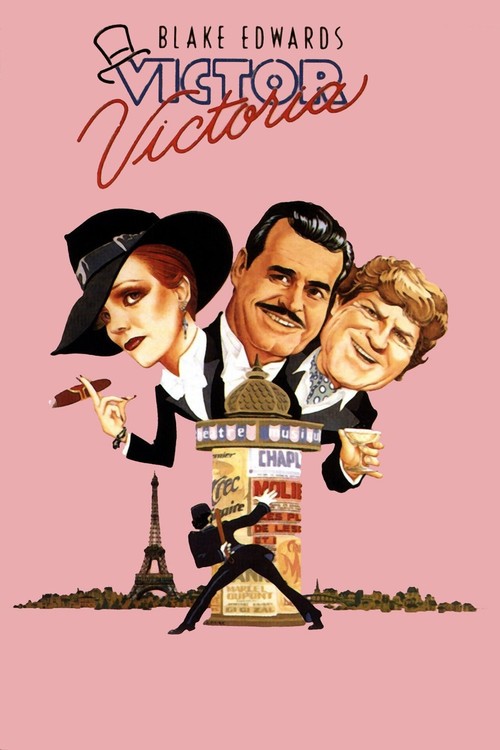

On-set frustrations aside, Blake Edwards got one other thing very right: hiring Henry Mancini to do the score. The two men had worked together three years before on Edwards’s TV show “Peter Gunn,” and Edwards quickly spotted this young composer’s brilliance.

When one thinks of movies where the score contributes significantly to the mood and spirit of the finished product, “Breakfast” has to make the short list. It also gave us “Moon River,” which the American Film Institute ranks as the fourth best movie song ever, after “Over the Rainbow,” “As Time Goes By,” and “Singin’ in the Rain.”

It’s ironic that after viewing an initial cut of the film, one studio executive commented: “Well, the first thing we can do is lose that song”. The producers and Hepburn replied in unison: “Over our dead bodies!”

At Oscar time, Hepburn was nominated, but it was Mancini who walked away with two Oscars: for Best Score, and, with Johnny Mercer, Best Song. Edwards and Hepburn, knowing a good thing when they heard it, would each tap Mancini to do the soundtrack for several more of their films.

“Breakfast” has one highly visible blemish: the misguided casting of Mickey Rooney as Holly’s Japanese landlord, Mr. Yunioshi. Producers suggested casting a Japanese actor, but Edwards insisted he wanted Rooney, who could give him the broad performance he was looking for. As attitudes about political correctness evolved over the years, both men would publicly express regret and apologize for causing offense.

One person Edwards didn’t need to apologize to was veteran actor Buddy Ebsen, hired for the small but crucial part of Doc Golightly, Holly’s first husband. He’d been almost set to retire from show business after a fallow period, but his appearance as Doc would reignite his career.

After seeing the movie, the producer of a new series called “The Beverly Hillbillies” was convinced that Ebsen would be ideal for the lead role of Jed Clampett, the father of a poor, rural family that moves to Beverly Hills when oil is discovered on their land.

Ebsen took the part, the show was a monster hit, and he would become a TV fixture, in that and other series, for over a quarter century.

So, why does “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” still exert such a hold over us? Several factors contribute: the film came out the month before JFK was elected President, and captures that brief feeling of optimism and possibility in the decade to come. Vietnam had yet to hit the headlines, and flower power was still years away.

It shows a Manhattan looking clean, bright, and colorful, with no sign of graffiti, crime, or homelessness. Thus it delivers a potent dose of nostalgia for an idealized, long-lost time and place.

Yet ultimately the film is a showcase for the looks, charm and talent of Audrey Hepburn in her prime, making a part she was terrified to play her very own. Then and now, we love her Holly, and we love her.