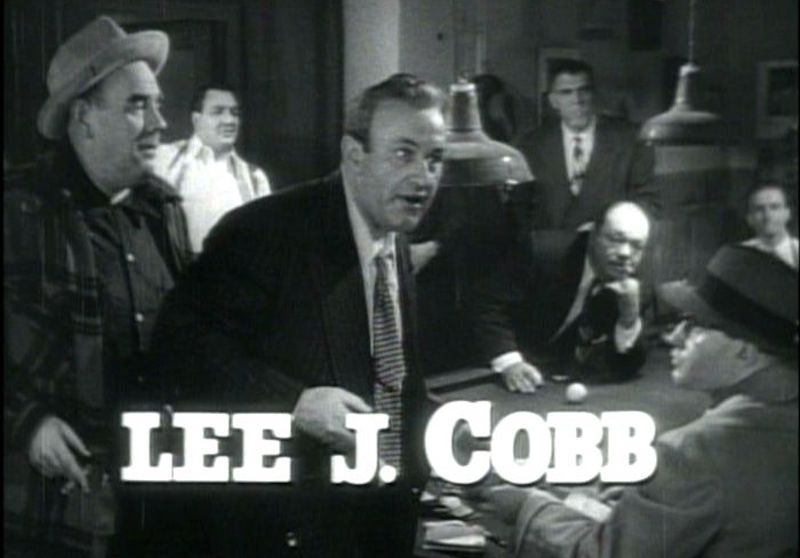

A close inspection of Lee J. Cobb’s film career, spanning nearly four decades, demonstrates what a versatile actor he was. Still, today he is best remembered for playing bitter, caustic, angry men.

When Cobb got angry on-screen, his intensity was frightening. Husky of body and voice, he excelled at playing intimidating men you didn’t want to cross. He was, in a word, volcanic.

Case in point: that pivotal scene in Elia Kazan’s “On the Waterfront” (1954) when former boxer Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) testifies against his character, mobster Johnny Friendly. The look on Friendly’s face when he gets fingered is one of towering, homicidal rage. No one could bring that off quite like Cobb.

He was born Leo Jacoby on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1911, the son of a typesetter for newspapers. He was a gifted violinist and harmonica player growing up, which fostered his love of performing. When a broken wrist derailed his future as a violin virtuoso, his highly practical mother encouraged him to get a degree in accounting.

Nothing doing. Even with an injured wrist, he could play the harmonica, and now he was also interested in acting. So, still in his teens, he set out for Hollywood with hopes of breaking into pictures. He found little success there, and soon found himself back home. Much to his mother’s satisfaction, a somewhat chastened Lee briefly took night classes in accounting, while pursuing acting jobs by day.

After a second Hollywood trip failed to spark any interest, Cobb landed back in New York again, where he resolved to focus on a Broadway career. Then, a break: at age 23, Cobb was admitted to the prestigious Group Theatre, a progressive training ground for the top emerging talents in the theater world — actors, directors, and writers. There he would first meet and collaborate with soon-to-be famous names like Elia Kazan, Clifford Odets, and John Garfield.

This recognition boosted Lee’s drive as he honed his craft in groundbreaking productions like Clifford Odets’ “Waiting For Lefty.” Two years later, he resolved to give Hollywood one more shot. This time, he would stay.

After doing a couple of forgettable Westerns, Lee used his Group Theatre connections to land a role in the screen adaptation of Odets’ play, “Golden Boy” (1939). The film was a prestige production and became a hit, introducing the public to a young actor named William Holden. Just seven years Holden’s senior, Cobb played his father.

Now the industry was finally ready to embrace him, and over the next decade, Lee appeared in 17 features, some of them enduring classics. After making “The Song of Bernadette” (1943), Cobb enlisted in the Army Air Corps for the duration of the war. In 1946, he was right back on screen, co-starring with Rex Harrison and Irene Dunne in “Anna and the King of Siam,” soon to be musicalized by Rodgers and Hammerstein as “The King and I.”

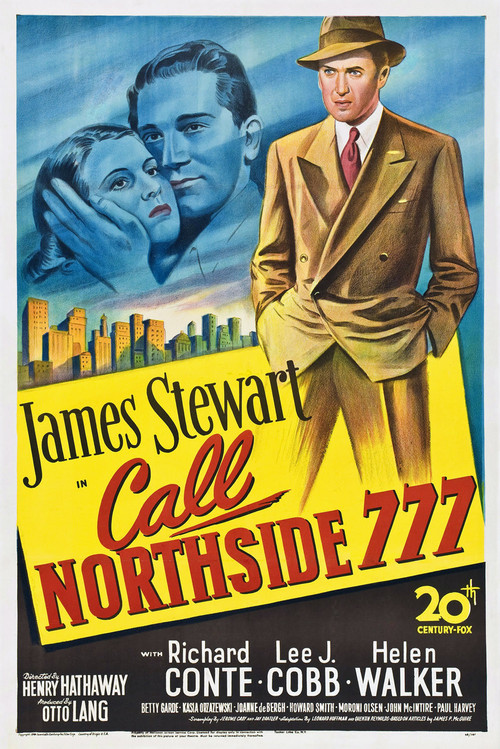

Then, in 1947, Cobb reunited with his old colleague Elia Kazan for the thriller “Boomerang” (1947), excelling as a dogged homicide detective.

Soon after, Kazan teamed up with a young playwright named Arthur Miller to produce a new play called “Death of a Salesman,” about a beaten down traveling salesman gradually descending into delusions and despair. Miller later said he always had Cobb in mind for the central character of Willy Loman, and predictably Kazan endorsed his choice.

Opening on Broadway in February, 1949, “Salesman” made history. It was a monster hit, an instant classic. Today it is widely considered one of the finest plays of the twentieth century.

By the time Cobb achieved this great success, America was entering one if its darkest periods, with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) aggressively investigating supposed Communist sympathizers in the movie industry. Those who refused to talk had their careers ruined.

Many Group Theatre alumni from the thirties were targeted, including Kazan, Odets, and John Garfield. Only Garfield refused to comply, and the stress brought on by his principled stand led to a fatal heart attack at the height of the uproar in 1952. Garfield was only 39.

Cobb at first resisted cooperating, but then, under enormous strain, his first wife Helen had a nervous breakdown and had to be institutionalized, precipitating a painful divorce. Fearing the loss of his livelihood and an inability to support his two children, Cobb finally agreed to cooperate and “name names” in 1953.

The next year came “Waterfront,” a huge success which won Oscars for Kazan, Schulberg and Brando, and earned Cobb his first nomination for Best Supporting Actor. (Featured players Rod Steiger and Karl Malden were also nominated).

Lee J. Cobb was now back on top professionally, but the ordeal of the past several years had taken its toll. In 1955, he suffered a serious heart attack. Still, he would not be sidelined for long.

1957, in particular, was a banner year for him. In the spring, Nunnally Johnson’s “The Three Faces of Eve,” about a young woman diagnosed with multiple personalities, was released to great acclaim. Importantly, the film allowed Cobb to play a relatively calm, thoughtful, intelligent character — a dedicated psychiatrist treating the title character (Joanne Woodward, in an Oscar winning turn).

Cobb then remarried over the summer. Second wife Mary Hirsch would bear him two more children, and their union would endure.

That fall brought director Sidney Lumet’s first feature, “12 Angry Men.” Focusing on jury deliberations which could lead to a murder conviction, among a stellar ensemble cast Lee was a standout as Juror Number 3. This brilliant, landmark film earned three Oscar nods, including Best Picture, and its stature has only grown in the decades since its release.

The following year, Cobb earned his second and last supporting actor Oscar nod for “The Brothers Karamazov,” starring Yul Brynner and Claire Bloom. (Though amazingly the film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, it received mixed reviews and has not aged particularly well).

In the last two decades of his life, Cobb stayed busy, bouncing between films, TV and the stage. Betraying where his own preferences lay, he once observed: “Theater is an actor’s medium; film is a director’s medium, and TV is nobody’s medium.”

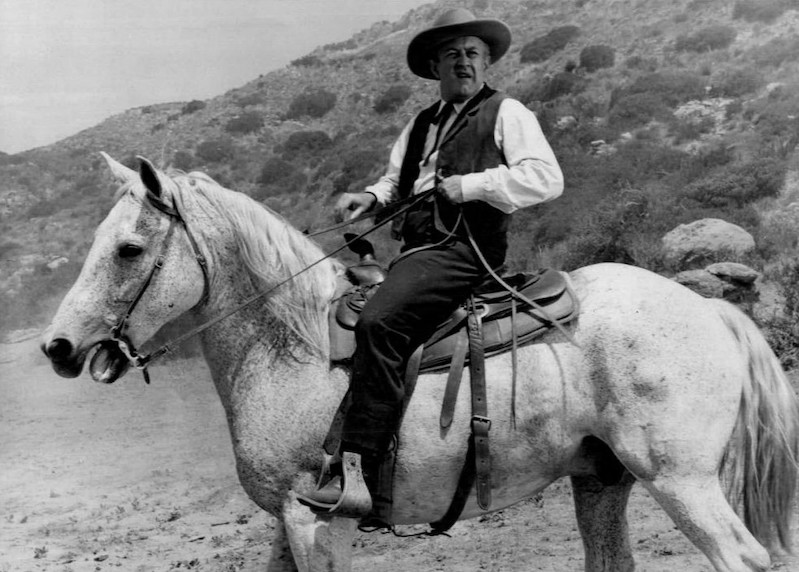

Still, TV paid a lot of bills, and beginning in 1962, Cobb signed up for a recurring role in the popular western series, “The Virginian.” He’d stay with the show until 1966.

Among his films during this period: “Exodus” (1960), “How the West Was Won” (1962), “Our Man Flint” (1966), and “Coogan’s Bluff” (1968), a police drama starring Clint Eastwood that would inspire the seventies TV series, “McCloud.”

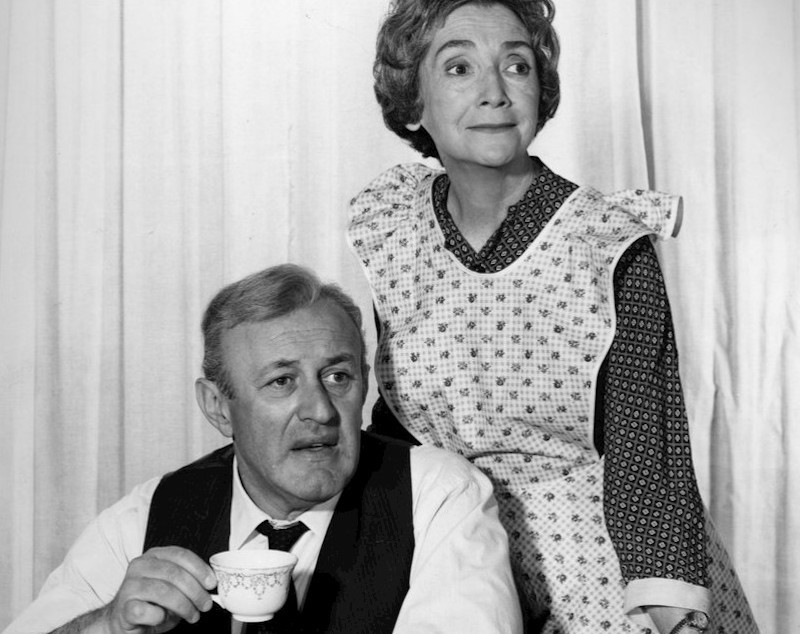

In 1966, the actor also returned to Willy Loman in a made-for-TV production of “Death of a Salesman.” Mildred Dunnock reprised her role as wife Linda, and the cast also featured George Segal, James Farentino, and a young Gene Wilder.

Two years later, he’d take on an even more challenging assignment: playing King Lear. Cobb, however, had never performed Shakespeare. It hardly mattered. Running for 72 performances, it sustained the longest run for the play in Broadway history. In his review, Times critic Clive Barnes commented that Cobb “…moves in with an interpretation that is non-heroic but humanly scaled with superb insight.”

Cobb would turn up in one more great film after this, playing a police investigator in William Friedkin’s 1973 shocker, “The Exorcist.” You don’t see that much of him, but when you do he makes every second count.

Lee J. Cobb suffered a fatal heart attack in Hollywood on February 11, 1976. He was just 64 and working right up to the end. On that otherwise unremarkable day, we lost a blazing talent who breathed life into Willy Loman, Johnny Friendly, Juror No. 3, King Lear, and so many others.

Though Cobb is irreplaceable, it’s a fitting tribute that another powerful actor, George C. Scott, would reinterpret three key parts that Cobb originated: Juror no. 3 in a 1997 TV remake of “12 Angry Men,” Lieutenant Kinderman in “The Exorcist III” from 1990, and on Broadway in 1975, Willy Loman.

Once, when asked to compare his two signature stage roles, Cobb responded: “If you must compare, [Willy] Loman is a half-beaker as against Lear’s full, overflowing beaker of poetry and emotion. The great difference is that in a production of Lear there is [a] challenge to continual growth. There is no such thing as perfection.”

Indeed perfection is elusive, in acting and in life, but watching Lee J. Cobb work his magic on stage or screen, you always knew he was going to come pretty damn close.