“Orson Welles lists ‘Citizen Kane’ as his best film, Alfred Hitchcock opts for ‘Shadow of a Doubt,’ and Sir Carol Reed chose ‘The Third Man’ — and I’m in all of them.”

Those are the words of Joseph Cotten, perhaps the finest screen actor never to be nominated for an Oscar. The more time passes, the more it feels like a serious oversight.

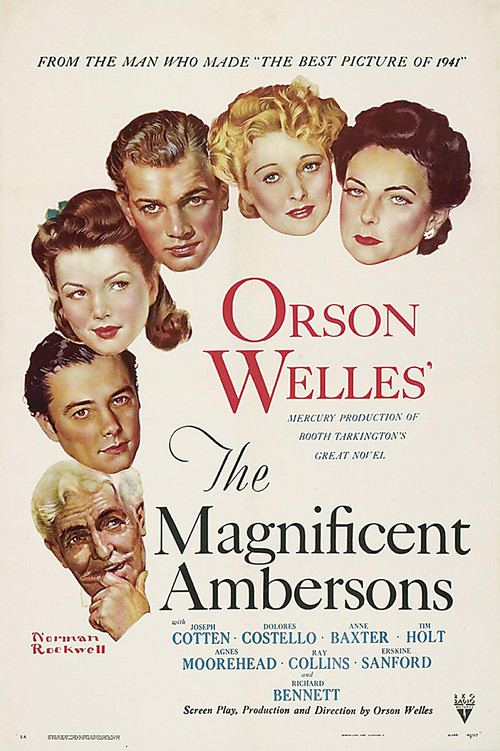

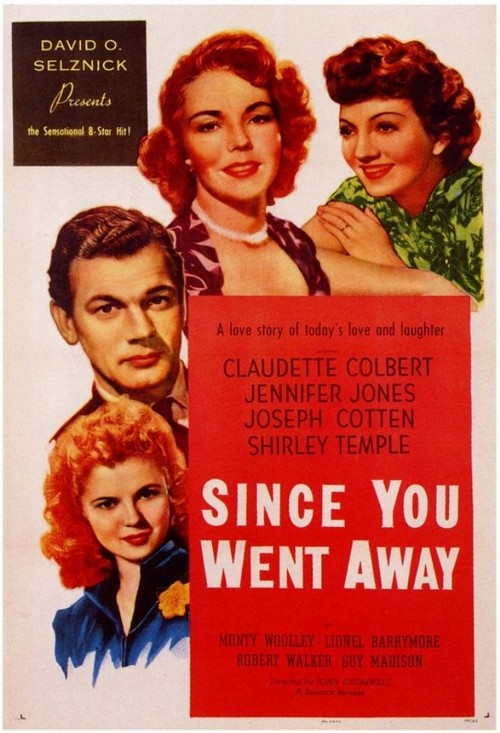

Consider this: along with close friend and colleague Orson Welles, he appeared in the top film selected for both the American and British Film Institutes: “Citizen Kane” (1941) for AFI, and “The Third Man” (1949) for BFI. Cotten also starred in four Academy Award nominees for Best Picture in just four years: “Citizen Kane,” “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942), “Gaslight” (1944) and “Since You Went Away” (1944).

Yet he himself was never nominated. Perhaps his measured demeanor and understated approach could be mistaken for blandness, but watch closely and his blazing talent shows through.

It didn’t help that Cotten himself tended to downplay his own abilities. Referring to his movie career, he once said: “I didn’t care about the movies really. I was tall. I could talk. It was easy to do.”

He was in fact an actor of great subtlety and skill. Critic Charles Champlin summed up his unique quality as follows: “The persisting core of Cotten’s work has been an elegant and unobtrusive craftsmanship which emphasized the role that Cotten was playing rather than the fact that Cotten was playing it.”

The eldest of three sons born into an old Virginia family, Jo (as he was always known) was drawn to performing early. At eighteen, instead of college, he ventured to Washington, DC to take voice and elocution lessons. In the mid-twenties, during the Florida boom, he moved to Miami, working a variety of jobs to support himself while working in regional theater.

But like all ambitious actors of the time, his eyes were set north to New York City, and Broadway. Finally, in 1930, Cotten was hired by famed producer David Belasco as an assistant stage manager. Soon after he understudied star Melvyn Douglas in “Tonight or Never.” Though he debuted on Broadway in 1932, it would take more time for him to break through.

Fortunately Jo had a good speaking voice, so was a natural for radio, as was another precocious, highly talented player ten years his junior named Orson Welles. The two men met in 1934, and quickly hit it off. It seemed inevitable they’d work together, and young Welles was hardly short of inspiration.

In 1936, under the auspices of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, he cast Cotten in “Horse Eats Hat,” a theatrical farce which drew a lot of attention. When Welles formed his Mercury Players the following year, Cotten became an inaugural member. He’d appear in several plays and radio programs under the Mercury banner.

All this increased exposure led to his big break: starring opposite Katharine Hepburn in the original production of “The Philadelphia Story” in 1939. He played C.K Dexter Haven, which Cary Grant would immortalize in the 1940 film version.

The following year, the 25-year-old Welles decided to conquer Hollywood, and negotiated a two picture deal with RKO. He had never directed or starred in a movie before. Now he’d do both, and cast his Mercury Players in his productions. Beyond Cotten, that group included Agnes Moorehead, Ray Collins, Everett Sloane, and Ruth Warrick.

Welles’s first film was, of course, “Citizen Kane,” with Cotten in the second lead as publisher Charles Foster Kane’s most trusted employee, Jed Leland. As controversial as that film was, it launched an incredible run for Cotten, particularly when (with Welles’s blessing) he signed a contract with famed producer David O. Selznick in 1943.

Over the next six years, he’d appear in a string of enduring classics. He’s unnerving as Teresa Wright’s psychopathic uncle in Hitchcock’s “Shadow of a Doubt”. He gallantly rescues Ingrid Bergman from the clutches of Charles Boyer in “Gaslight,” and becomes obsessed with an ethereal beauty (Jennifer Jones) in “Portrait of Jennie,” for which he won the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival.

Finally, and perhaps most memorably, he ventures to crumbling post-War Vienna and gets embroiled in some nasty black market intrigue in “The Third Man.” Many people still think of this as a Welles film, because the whole plot revolves around his character. Still, Welles has only a few minutes of screen time, while Cotten is in most every scene. It’s really his film.

Though he’d never again match the quality of his output in the forties, Joseph Cotten kept busy working in movies, television and theater over the next three decades. “I was in a lot of junk,” he said years later. “I get nervous when I don’t work.”

He lost his first wife of thirty years, Lenore Kipp, to leukemia in 1960. Later that same year, he married British actress Patricia Medina, and their union lasted till Cotten’s death in 1994, age 88. He had one stepdaughter from his first marriage, but never fathered kids of his own.

Over the years, Jo maintained his relationship with Orson Welles. Though there were tempestuous moments — inevitable with a volcanic personality like Welles’s — a core of affection and respect held between them.

Referring to Welles, Cotten said: “I still think he’s one of the greatest directors in the world. I don’t know why people regard him as a difficult man. He was the easiest, most inspired man I’ve ever worked with.”

When Cotten suffered a major stroke in the early eighties which necessitated speech therapy, the two men had extended conversations by phone, which heartened Jo and speeded his recovery.

In late 1985, Welles had just finished reading a draft of Cotten’s autobiography, eventually published as “Vanity Will Get You Somewhere.” Speaking to a friend, he referred to it as “gentle, witty and self-effacing, just like Jo.” The next day Welles died.

You may have forgotten Joseph Cotten, but you can’t forget his best films. For that, Jo, we thank you.