Ida Lupino is a largely forgotten name that deserves to be remembered.

She started as an ingenue in the thirties and through sheer pluck and determination, went on to become one of the only female directors in Hollywood. She was a trailblazer who found her own way to compete — and succeed — in a virtually all male world.

It’s still astonishing how few prominent female directors there are today, but it used to be even worse. Though pioneers like Lois Weber and Dorothy Arzner managed to penetrate this boys’ club early on in the silent period, their names and work are largely lost to history.

By the time Lupino came along, the studio system was in full swing, and for the most part, women were either actresses or stenographers. (There were a few screenwriters as well, like Frances Marion, Catherine Turney and Leigh Brackett; yet they were never as famous or prominent as some of their male colleagues).

Ida Lupino was born in England, and descended from a family with a long and rich show business tradition. Her mother Connie was a working actress, her father Stanley a successful music hall entertainer who encouraged both his daughters to perform, even building a working stage in their backyard when Ida was still very young.

Ida secretly wanted to be a writer, but felt considerable pressure from her family to act. An early stint at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA) followed by stage and screen work in England confirmed she had abundant talent.

She arrived in the States in 1933, age 15, and promptly set out for Hollywood. Applying lots of peroxide, she became a platinum blonde and was initially built up by Paramount Pictures as “the English Jean Harlow.” Shortly thereafter, she contracted polio, which laid her up for some time and made her resolve not to have her career depend solely on her physical appearance and abilities.

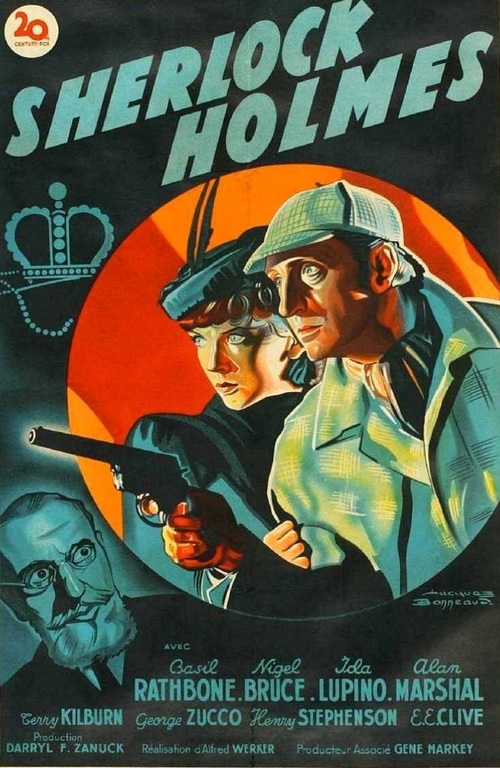

Once recovered, she worked fairly steadily throughout the thirties, without really breaking through. 1939, often considered Hollywood’s finest year, brought a turning point for her. She was memorable as the femme fatale in “The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes” and then delivered an impressive turn in the Ronald Colman film, “The Light That Failed,” directed by William Wellman.

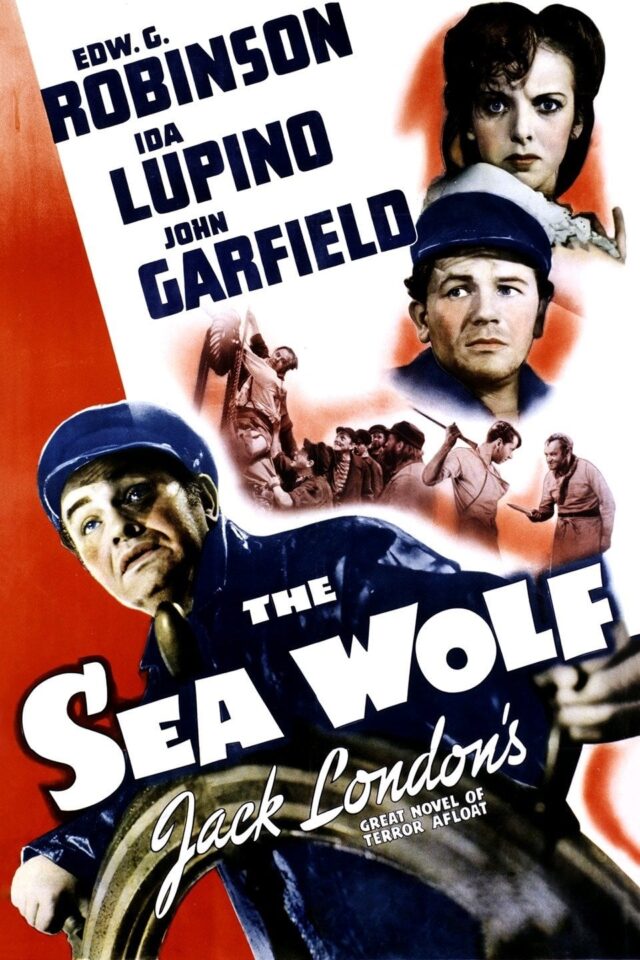

Warner Brothers then came calling, and it was at this studio that Lupino finally became a star. Over the next two years, she would appear in three classics back-to-back: “They Drive by Night,” “High Sierra,” and “The Sea Wolf.”

Ida Lupino had arrived, but as the decade wore on, she half-jokingly called herself “the poor man’s Bette Davis,” as she inevitably played the roles which the older, more established actress had rejected.

Lupino was always a trouper, but hated waiting between takes while, in her words, “others were doing all the interesting work.” Thus began her interest in directing.

As time went on, there were also several roles Ida refused to play, which infuriated Jack Warner and brought on suspension by the studio. During these fallow periods, she began visiting sets, watching the director and the crew work, and picking up techniques and advice which would serve her well later.

She finally left Warner Brothers in 1947, and soon after formed a production company with her second husband Collier Young (Lupino had been previously married to actor Louis Hayward). Their intention was to produce and direct a series of lean, low-budget independent films dealing with controversial social issues the major studios wouldn’t touch (including bigamy and rape).

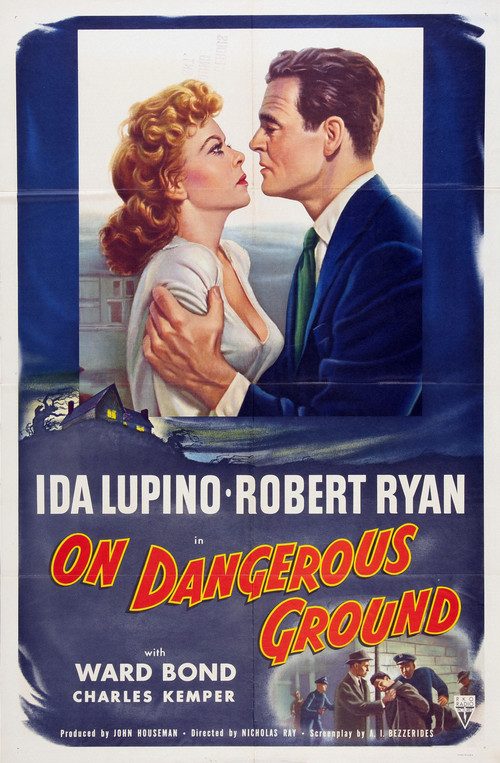

Ida helmed several of these pictures, shooting fast and cheap yet still creating quality work. In 1953, she became the first female ever to direct a film noir with the release of “The Hitch-Hiker.

For a twelve year period beginning in 1956, Ida would direct episodes of many classic TV programs, including The Donna Reed Show, 77 Sunset Strip, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Rifleman, The Untouchables, and Bewitched. She became the first person to both direct and star in Rod Serling’s hit series, The Twilight Zone, and the only woman to direct.

In 1951, she’d divorced Young to marry actor Howard Duff, and the couple had a daughter, Bridget. Lupino quit directing at 50, and retired from acting at 60, in 1978. Five years later, she divorced Duff.

In 1995, Ida Lupino died of a stroke while receiving treatment for colon cancer. She was 77.

For those unaware of her life and work, the titles below will introduce you to an extremely talented actress. The fact she was able to parlay her stardom into a directorial career speaks volumes about her shrewdness, perseverance and ample gifts behind the camera, as well as in front of it.

To have achieved this in the hyper-conservative 1950s is all the more extraordinary. Ida Lupino, actor, director, producer, we salute your remarkable achievements, and we will not forget.