I was lucky enough to know Gene Wilder. That’s not to boast but to affirm a tired old cliché: to know him was to love him.

I’ve encountered a number of movie luminaries over the years, and – no surprise — quite a few have exhibited “star attitude”— a somewhat defensive, wary posture that often comes with fame. However subtly it’s displayed, it’s unmistakable.

There was not a trace of that in Gene. For all the attitude he had, he could have been your favorite uncle or that special teacher you stayed in touch with. He was surprisingly reserved, but once comfortable with you, that trademark twinkle shone through. His keen wit and intelligence made him excellent company, and unlike some actors, he listened as intently as he spoke.

Gene was a resident of Stamford, Connecticut in his later years, and I met him because I was involved in bringing back an historic cinema there, The Avon. We reached out to him in 2004 hoping he might support our efforts.

Rather than hide from us behind his executive assistant, he readily agreed. Over the years, he’d serve on our Advisory Board and make several appearances at the theater, which brought out big crowds and gave the Avon much needed publicity.

His innate shyness meant these public appearances were not necessarily a pleasure for him. He did it because he cared about his community, movies, and movie theaters. And he knew that this was how he could be most helpful.

My favorite Gene Wilder memory happened at a weekend matinee screening of “Willy Wonka and The Chocolate Factory” (1971). This was not Gene’s favorite of his films, and had not done particularly well on release, but it had become a cult hit after years of TV airings and eventually, a release on home video.

It was a lovely late morning, and we were both standing outside the theater, when in the distance we spied several noisy packs of excited children approaching us. Comically clenching his teeth, Gene leaned towards me in mock apprehension and said in a stage whisper, “Oh, my God. They’re coming. Here they come. Oh God.”

When the rapturous kids finally caught up with their hero, Gene beamed and channeled Willy Wonka. It seemed he’d done a few of these events before.

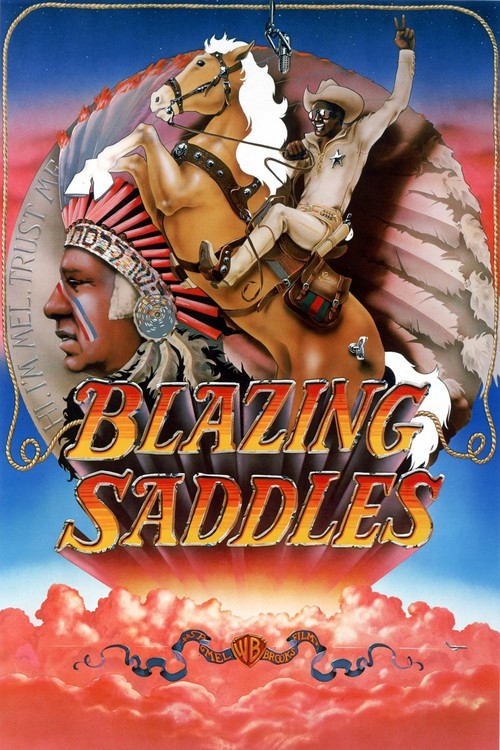

His favorite movie, by far, was “Young Frankenstein” (1974). It had started out as his idea, his project. Arriving on the set of “Blazing Saddles” the prior year, he’d immediately approached Mel Brooks and said, “I have an idea, and I want it to be your next picture.”

When Gene laid out the Frankenstein idea, Mel raised the concern that the story had already been done to death, with sequel after sequel produced at Universal in the ‘30s, and Britain’s Hammer Films taking up the mantle again in the ‘60s. But Gene was not to be deterred, and finally convinced his colleague and partner to come in on the project. He and Gene would collaborate on the screenplay, while Brooks would direct.

There was one condition: Mel could not appear in the film. Wisely, Gene recognized Mel’s proclivity for “breaking the fourth wall” and Wilder did not want this to happen with “Young Frankenstein.” He wanted it to be a reverent spoof of those classic Universal pictures. Both men agreed that to achieve that goal, any studio would have to approve their shooting in black and white. After Columbia Pictures balked at this, the filmmakers moved over to Twentieth Century-Fox.

The casting came together (Marty Feldman, Peter Boyle, Kenneth Mars), with one small hitch: Madeleine Kahn was originally slated to play Freddie Frankenstein’s assistant, but decided she rather take on the role of his fiancée. This put Mel in an awkward position with Teri Garr, then a relative unknown, who’d been cast as the bride-to-be. Now only the role of the assistant was open, but would she be right for it?

“Come back tomorrow and give me a good German accent, and you’re in,” Mel told her. Teri didn’t wait, but executed a perfect one on the spot, and the part was hers. (Garr later said that she simply imitated Cher’s German wig maker, whom she’d met while working on The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour two years prior).

There is a superstition in Hollywood that happy sets usually produce indifferent movies. If that’s even true, “Young Frankenstein” was a notable exception. It was the happiest set that Gene would ever experience; often he had to do numerous re-takes of scenes simply because he could not keep his composure. Mel Brooks claimed that no one wanted it to end, that in fact new scenes were developed just so the production could continue.

Perhaps as a result, the first cut was too long and decidedly uneven. Thus began a process of tightening the film and removing all but the funniest bits. The movie would eventually clock in at 106 minutes of sustained hilarity. (Thankfully, Gene Hackman’s unbilled cameo as the blind man who drives away the monster made the final cut. Hackman, who’d appeared with Gene in “Bonnie and Clyde,” told his friend over a set of tennis that he’d love to try a comedy, and Gene snapped him up.)

Both critics and the public loved the finished picture. In The New York Times, Vincent Canby stated that “although it hasn't as many roof-raising boffs as ‘Blazing Saddles,’ it is funnier over the long run because it is more disciplined. The anarchy is controlled.”

A young Roger Ebert echoed that sentiment: “‘Young Frankenstein’ is as funny as we expect a Mel Brooks comedy to be, but it’s more than that: It shows artistic growth and a more sure-handed control of the material by a director who once seemed willing to do literally anything for a laugh. It’s more confident and less breathless.”

This subtler, more assured comic approach was really what Gene brought to the movie, and to his credit, Mel Brooks knew it and acknowledged it.

Right now we are all missing Freddie Frankenstein, and Willy Wonka, and gunslinger Jim from “Blazing Saddles.” Then, of course, there’s my own personal favorite (other than Freddie): Leopold Bloom in “The Producers” (1967), the role that made Gene a star and earned him his first and only Oscar nod for acting.

I always go back to one scene in that movie: Leo screams “I’m hysterical!”, and Zero Mostel’s Max Bialystock throws water on him. Leo says: “I’m wet! I’m wet! I’m hysterical and I’m wet!” Bialystock slaps him. “I’m in pain! I’m wet! And I’m still hysterical!” It’s one of the funniest moments in comedy, and really, it’s all Gene.

Aside from those memorable roles, I’m also thinking about the quiet, gracious man who helped us bring back the Avon Theatre in Stamford, and who stood with me that sunny morning and made me laugh as an unruly horde of kids approached.

Goodbye, Gene, and thanks.

More: Why 1974 Was Mel Brooks' Best Year