Gloria Grahame never quite became a star in Hollywood, but she sure left her mark.

If you’re a fan of film noir, you know her already. This shadowy world of double-and triple-crosses was where she thrived. Still, even casual fans of older films will remember that face, that voice, that look.

To say she was sexy understates it; Gloria Grahame was positively dangerous. Her heavy lidded eyes, husky voice, and perfect figure posed a triple threat to any man with blood pumping in his veins. She summarized her own impact by saying, “It wasn’t the way I looked at a man; it was the thought behind it.”

Her off-screen life was filled with as much drama as anything that happened on-screen. Yet though she had plenty of “peaks and valleys” in her life (her words), she was a trouper, who worked right up to her death.

Acting came to her naturally, and early. Born in Los Angeles to an architect father and former actress turned acting teacher, she studied under her mother from childhood. By her teens, it was clear Gloria had considerable talent, and she was so smitten with performing that she didn't even bother to graduate from Hollywood High.

Instead, she went on-stage, and several years later, was spotted in a Broadway play by Louis B. Mayer, who signed her to a standard MGM contract in 1944. Gifted as she was, MGM did not quite know what to do with her: her beauty was unconventional, and her overtly sensual mien did not fit the wholesome image of the classic mid-forties ingénue.

She played the first role we all remember her for when she was on loan-out to Columbia: the flirtatious Violet Bick, who holds a candle for Jimmy Stewart’s George Bailey in the perennial classic, “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946). As with many Grahame performances to come, her part isn’t a major one, but still she stands out. You can’t help but remember her.

MGM finally sold her contract to RKO, and her new studio seemed to know just how to use her. Right out of the gate, Gloria’s performance as a dance hall girl in the early noir “Crossfire” (1947), won her an Oscar nod for Best Supporting Actress.

Chiefly remembered as the first movie to address anti-Semitism (months before the better-known “Gentleman’s Agreement”), the film also won an Oscar nomination for co-star Robert Ryan, and paired Gloria with relative-by-marriage Robert Mitchum, whose brother had married her sister.

Grahame gave perhaps her meatiest performance in Nicholas Ray’s dark drama, “In a Lonely Place” (1950), starring Humphrey Bogart. (Grahame was married to Ray at the time). Bogie plays Dixon Steele, a screenwriter with a notorious temper who’s suspected of murdering a hat-check girl he’d invited home the night before. Gloria is his comely neighbor Laurel Gray, who, for reasons we don’t fully understand, furnishes him with a very convenient alibi. Romance blooms, but will it last? And is Dixon really innocent?

Other great films followed, including the tingling “Sudden Fear” (1952), and that same year, Robert Wise’s excoriating drama about the cutthroat movie business, “The Bad and the Beautiful.” For the latter film, Gloria received another Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, and this time she won.

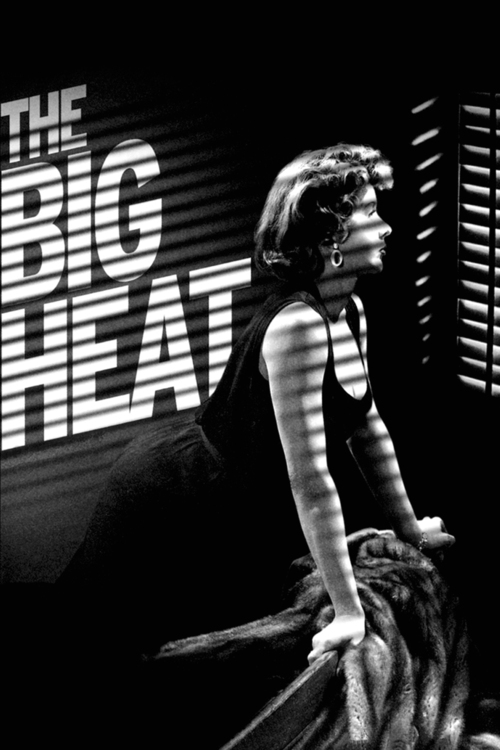

Now on a roll, she’d execute her most memorable turn the following year in one of the all-time best noirs, Fritz Lang’s “The Big Heat.” Gloria plays Debby Marsh, a gangster’s moll who gets too close to vengeful detective Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford). To teach her a lesson, her thuggish boyfriend Vince Stone (Lee Marvin) throws a pot of scalding coffee in her face. The scene is indelible, as is the film.

Two years later, Grahame’s luck started to run out. She was miscast as Ado Annie in the musical “Oklahoma!,” and was reported to be extremely difficult on the set. Then and now, unless you’re a bona fide star who can draw big box office, murmurs about being hard to work with can be poisonous.

Gloria’s personal issues didn’t help. She’d always been obsessed with her appearance, convinced her thin upper lip was a serious drawback. This resulted in several plastic surgery operations that eventually caused nerve damage, affecting her speech.

In addition, Grahame’s notorious fourth and final marriage would trigger a tremendous scandal. In 1951, second husband Nick Ray arrived home to find Gloria in bed with his fourteen-year old son Tony, from his first marriage. Not surprisingly, that ended the marriage. Then, after divorcing her third husband, writer/producer Cy Howard, in 1957, Gloria became seriously involved again with her former stepson. The two would marry in 1960.

This shocking development became tabloid fodder, and caused both her second and third husbands to seek custody of the children they shared with her (twelve-year old Timothy with Ray, and four-year old Paulette with Howard). Gloria would spend a lot of time and money in court, and all the stress and scrutiny led to a mental breakdown and a regimen of shock treatments.

Her marriage to Tony, which produced two children, Anthony and James, became ugly as their finances dwindled; they would finally divorce in 1974. That same year, Gloria was diagnosed with breast cancer, but with treatment the disease went into remission.

Amidst all this tumult Grahame never stopped working for very long. Acting seemed to be her only solace. Though her film career was effectively over by 1960, she did theater and appeared on television in a host of successful shows, from “The Outer Limits” to “Kojak.”

When her cancer returned in 1980, Grahame chose not to treat it. She died on October 7, 1981 in New York City, just hours after flying in from England. She was just 57.

Gloria Grahame once said of her years in Hollywood: “I was there for years under contract to MGM, RKO, and Paramount... I don't know how many others…actually, I remember everything, even the dates. But I don't want others to remember the details, just the image.”

We remember, Gloria. We remember.

More: 8 Unmissable Film Noir Classics You've Likely Missed