“I intend to live the first half of my life. I don’t care about the rest.”

Movie star, athlete, yachtsman, writer, adventurer and overall wild man Errol Flynn gave the world many memorable quotes, but the one above may be the most revealing.

It captures precisely how he lived, on a more perilous, exhilarating and reckless scale than the rest of us. Show him a rule or a law, and he wanted to break it, for the sheer excitement of it.

Errol Flynn was born in 1909 in Australia, the son of a biology professor. He was wild and rambunctious from the start — unruly in school and prone to mischief. He would be expelled more than once.

With formal education finally a lost cause, Errol resolved to make his fortune in the real world. He was just seventeen. After getting fired from his first job in Sydney, he ventured off to the wilds of Papua New Guinea to try his hand at planting or mining. He’d go back and forth between there and Sydney over the next several years, amassing an incredible number of scrapes and adventures along the way, but alas, no fortune.

That chapter behind him, and at loose ends, Errol thought he’d try acting and appeared in his first Australian film in 1933. He liked it enough to pursue more acting training, and won a spot with the Northampton Repertory Company in England. There, an incident with a female employee got him the sack once more.

Back at Teddington Studios in Middlesex, he was finally ready to shine, winning the starring role in a lost film intriguingly titled “Murder at Monte Carlo.” Impressed by his looks and talent, Warner Brothers signed Flynn to a standard contract, and at age 25, he was on his way to Hollywood.

What happened next is right out of a movie. Having arrived safely, Errol had gone straight to work, dutifully playing two minor roles in programmers starring Warren William. He was fully prepared to continue paying his dues and building his credits for a while.

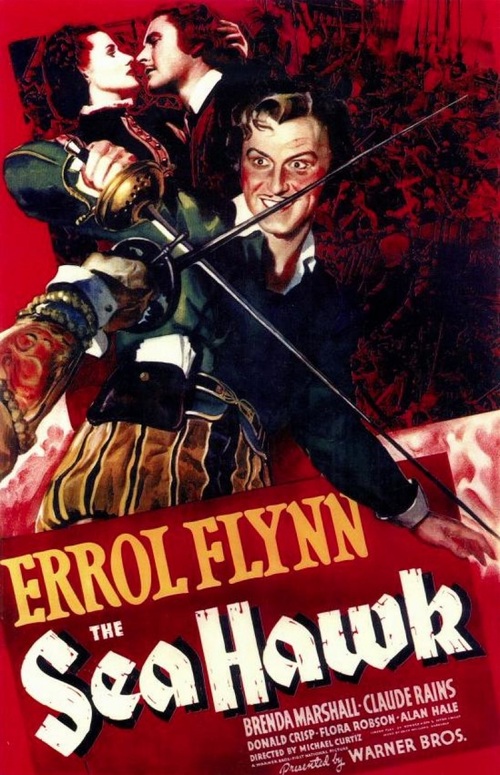

Meanwhile, British star Robert Donat, famous for “The Private Life of Henry VIII” (1933), “The Count of Monte Cristo” (1934), and most recently Hitchcock’s “The 39 Steps,” was slated to play the sword-wielding hero Peter Blood in the swashbuckler “Captain Blood,” based on a Rafael Sabatini book. Donat had periodic health issues throughout his life, and exhausted after a slew of pictures, he fell ill. A replacement had to be found fast.

Errol was considered for his youthfulness and athleticism, alongside more seasoned players like George Brent. It was clear he’d be able to do most if not all of his own stunts. The studio decided to take a chance on him.

The movie was a smash, and overnight made Errol Flynn the successor to Douglas Fairbanks as Tinseltown’s favorite swashbuckling hero.

Reflecting the studio system of the day, Errol’s director on “Blood” (Michael Curtiz) and female lead (Olivia de Havilland, also an unknown at age nineteen) would work with him on a succession of pictures in the years to come, perhaps most notably 1938’s “The Adventures of Robin Hood.”

Flynn and de Havilland liked each other and enjoyed a strong physical chemistry (though unconsummated, as Flynn had just wed first wife Lili Damita). Curtiz and Flynn, on the other hand, consistently loathed each other, but neither could argue with the success of their collaborations.

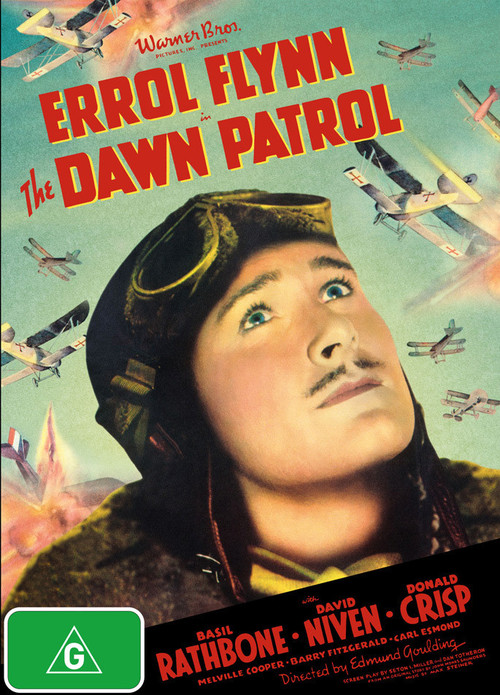

Errol enjoyed a string of high-profile hits over the next several years, and was at the peak of his career when he gained American citizenship in 1942. He promptly sought to enlist in the war effort, but was rejected due to a weak heart, chronic back issues, and a recurring case of malaria he’d first caught in New Guinea.

Flynn was bitterly disappointed. Worse yet, the studio was unwilling to go public with an explanation, not wanting to suggest their top action star was not in the best of health. So — as Flynn continued making movies during the war, a cloud hung over him with his fans. Did he not want to serve his adopted country?

Meanwhile, his wild ways finally caught up with him that same year, when two underage girls accused him of statutory rape. The scandal was public and messy, and though Errol was eventually acquitted, his image and reputation took a beating.

Damita divorced him, but Errol would re-marry second wife Nora Eddington the following year. (Nora was a waitress who bonded with Flynn serving him lunch during the rape trial). All the while, his heavy drinking and carousing continued unabated.

Then, with the war over, a new kind of film emerged. Grand adventure tales suddenly seemed outmoded, as a darker, more furtive and cynical worldview gave birth to the shadows of film noir. The likes of Errol Flynn seemed to have no place in this realm.

After a run of indifferent pictures, Jack Warner finally terminated his contract in 1950. After a 15 year run, Flynn’s film career was basically over. He was just 41. That same year, having divorced Nora, he embarked on his third and final marriage to actress Patrice Wymore.

The following years found Errol doing the occasional inferior feature, or sailing around on his beloved yacht, the Zaca, draining his savings and as always, drinking to excess. He relocated with Patrice to Jamaica, partly to distance himself from legal issues at home.

He sired daughter Arnella with Patrice, having already had three children with his other wives (his only son, Sean, with Damita, and two other daughters, Deidre and Rory, with Nora). Beyond Errol being an inconstant father (at best), all these dependents only increased the financial pressure already burdening him.

His third marriage proved as unsuccessful as his first two, and eventually Errol and Patrice separated. About his marriages, he once quipped: “Women won’t let me stay single, and I won’t let myself stay married.”

The late fifties saw him following the tragic path of his old friend John Barrymore, doing a series of roles that amounted to self-parody, playing alcoholics in 1957’s “The Sun Also Rises” and 1958’s “Too Much, Too Soon” (where he actually portrayed Barrymore). By this point, the ravages of drinking made him look at least a decade older than his real age, and his health was failing.

Facing financial ruin in late 1959, he was forced to travel to Vancouver with his fifteen-year old “secretary,” Beverly Aadland, to lease his beloved yacht. There he suddenly collapsed and died of heart failure. He was just 50. An autopsy indicated that if his heart hadn’t given out, he’d have died of cirrhosis of the liver within a year. He had the body of a 75-year old man.

His autobiography, “My Wicked, Wicked Ways” was released posthumously, to great acclaim. It was little surprise, really: Flynn was literate, clever, and told a great story. One critic commented at the time that even if only one-quarter of his anecdotes were true, Flynn had still led an amazing life.

By all accounts, Errol Flynn died without regrets. He’d lived outrageously, as he’d always intended to. He did not see old age, but never wanted to. He was like a rocket that soared very high, very fast, and then sputtered to earth. And rather than regret his dissolute reputation, he seemed to revel in it.

As if summing up his own philosophy of life, he once said, “It’s not what they say about you. It’s what they whisper!”