Just like the image of her fragile, unconventional beauty trapped within the glow of a tight spotlight, Judy Garland’s life as a performer was surrounded by a vast darkness. She gave the world her special gift, and it gave back not a shred of happiness. There was an overarching sadness about her that only grew more pronounced as the hard years went by. As Frank Sinatra put it, “When she sang, it always felt like she died a little.”

It was tragic pretty much from the outset. When overbearing show mom Ethel Milne found she was pregnant with her third child by husband Frank Gumm, she attempted to induce miscarriage by throwing herself down a flight of stairs. Failing that, she tried to get an abortion. This desire may have partly stemmed from Ethel’s growing suspicion that her husband was homosexual. Regardless, a family friend finally convinced the couple that this little one would be a blessing. They hoped for a boy.

On June 10, 1922 they welcomed their third daughter – Frances Ethel Gumm – the combined hopes of her mother and father right there in her name.

“Baby” Gumm made her first stage appearance at two and a half – enjoying it so much that by the fifth rendition of “Jingle Bells” she had to be carried off the stage. From that moment on, she was constantly performing. It was partly a way of distracting herself from her dysfunctional home life; the love of an audience passed for what she was not getting off-stage.

The Gumm family would move from Minnesota to Southern California, where Frances and her two siblings, billed as the “Gumm Sisters,” would endure countless classes, auditions, and performances – with mother Ethel as their agent. The act broke up in 1935, and Frances, clearly the most talented of the trio, was soon discovered by the MGM studio machine.

As she herself put it, “I was born at the age of 12 on a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lot.” Rumor has it that studio head Louis B. Mayer himself was brought down to hear her audition, and her contract was immediately drawn up. From then on, she would be Judy Garland: studio property, and treated as such.

Two months after signing her contract, tragedy struck when Judy’s father passed away of complications from spinal meningitis. On the day her father went into the hospital, MGM had her scheduled to make an appearance on the “Shell Chateau” radio show. They told her to put extra emotion into her rendition of “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart!”, as her father would be listening. He died the next afternoon, and Judy was heartbroken. “My father’s death was the most terrible thing that happened to me in my life,” she repeated over the years.

Judy languished in relative obscurity at MGM until she was booked to sing “You Made Me Love You” at Clark Gable’s surprise birthday party in February of 1937. At that moment, Mayer took real notice, and kept 15 year-old Judy on a frantic schedule of film after film. She was teamed with fellow juvenile star Mickey Rooney in a string of “backyard” musicals — nine in all. As teenagers, by law, both had to attend school in the morning, taught by studio tutors, with shooting commencing in the afternoon.

To keep their young actors’ energy up, studio doctors prescribed a regimen of pills. The way Judy tells it, “[MGM] had us working days and nights on end. They’d give us pep-up pills to keep us on our feet long after we were exhausted. Then they’d take us to the studio hospital and knock us cold with sleeping pills . . . Then after four hours they’d wake us up and give us the pep-up pills again so we could work another 72 hours in a row.”

Sensitive about her body image, and being compared to other beautiful MGM stars like Lana Turner, Judy was constantly nagged about her appearance and threatened with having her contract torn up. Weight fluctuations were a huge issue, and the studio heads, particularly Mayer, were brutal — referring to her as “the fat one” and “my little hunchback.”

Judy was “just a smidgen under five feet” (as Mickey Rooney told it), but her weight would swing from just 85 to 155 pounds at various times in her life. To keep her slim, the studio put her on diets (one reportedly consisted of chicken soup and 80 cigarettes a day to keep her hunger at bay). Also the amphetamines were in constant supply, leading to a life of addiction.

In 1939, Judy was cast as Kansas farm girl Dorothy Gale in “The Wizard of Oz,” and immediately rocketed to stardom. But fame would prove difficult for her, emotionally and physically. She was forcibly reshaped into the image the studio chose for her. For the role of Dorothy, Judy’s breasts were squashed down with tape, and she was made to wear a medieval-type corset to flatten out her curves and give her a younger appearance. Facial prosthetics were applied during filming too, including removable caps on her teeth and rubberized disks to reshape her nose.

In 1940, when the immortal song “Over the Rainbow” earned Judy a special Juvenile Oscar, it was an award earned through pain.

Though at the time she was still considered a juvenile performer, she longed for adult roles. But when she tried to play a grown-up in real life, only scandal followed. She eloped with bandleader David Rose in 1941 (at just nineteen), then became pregnant. Both the studio and her husband convinced her that to maintain what was left of her “good girl” image, she should have an abortion. This decision would haunt her for the rest of her life, and hasten the end of her marriage; she divorced Rose in 1943. He was to be her first of 5 husbands.

Even outside marriage, the adult Judy was always looking for love and approval. Her many affairs over the years would include Tyrone Power, Yul Brynner, Orson Welles, Frank Sinatra, and James Mason. Though these dalliances may have been fun in the moment, none gave Judy any lasting satisfaction.

In 1942 Judy garnered top billing for the first time, playing alongside George Murphy and Gene Kelly in “For Me and My Gal” (1942). Two years later she would meet her second husband, director Vincente Minnelli, on the set of “Meet Me In St. Louis”(1944). Judy always believed that Minnelli was the one director that knew how to bring out her beauty; she may have loved him for that alone. They’d collaborate on several films together, and once married, on a daughter as well: Liza, born on March 12, 1946.

After just nine months, Judy was back at work, filming Minnelli’s “The Pirate” (1948). By this time, Judy’s marriage — and mental health — were quickly deteriorating. She was often hallucinating, making false accusations, and being difficult on set. 1948 brought the delightful “Easter Parade” as well, co-starring Fred Astaire, but it would not bring Judy any joy. A string of suicide attempts followed the wrapping of this picture, and she was checked into rehab in 1949.

After being suspended three times from MGM for her erratic behavior she was fired in 1950, just as her second marriage was dissolving.

Judy went out on the road, performing for sold-out crowds in London, and then married producer Sidney Luft in 1951. Her career had to be put on hold again when she became pregnant with second daughter Lorna. By this time, her relationship with her mother had collapsed, and Judy refused to let Ethel see her new granddaughter. When Ethel died in 1953, Judy was wracked with guilt.

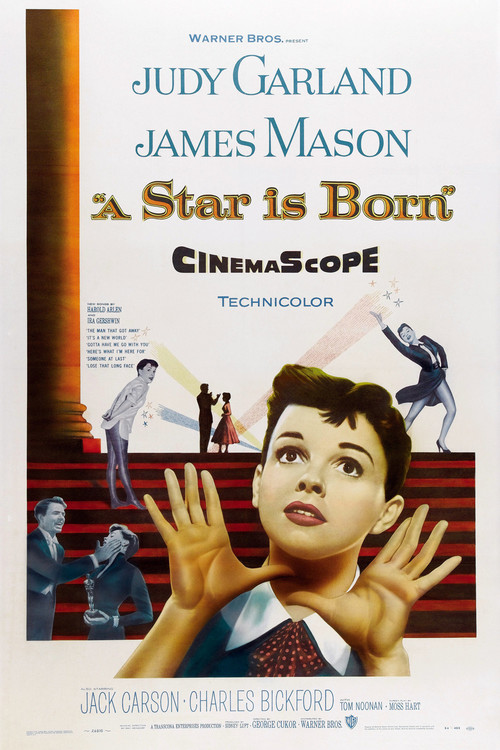

In 1954, she signed a contract to star in a remake of the 1937 musical “A Star is Born.” The film, produced by Luft, features a stunning performance by Garland, and her rendition of “The Man That Got Away” may be her finest moment on-screen. For this triumphant comeback vehicle, Judy won the Golden Globe and received an Oscar nomination (Check it out below!).

When Grace Kelly eked out the win for her work in “The Country Girl,” Judy was crushed. Her third marriage in turmoil and their fortunes floundering because of Sid’s gambling addiction, Judy had her third child, Joey Luft, in 1955, and a long hiatus from the screen ensued, during which she toured and did television specials.

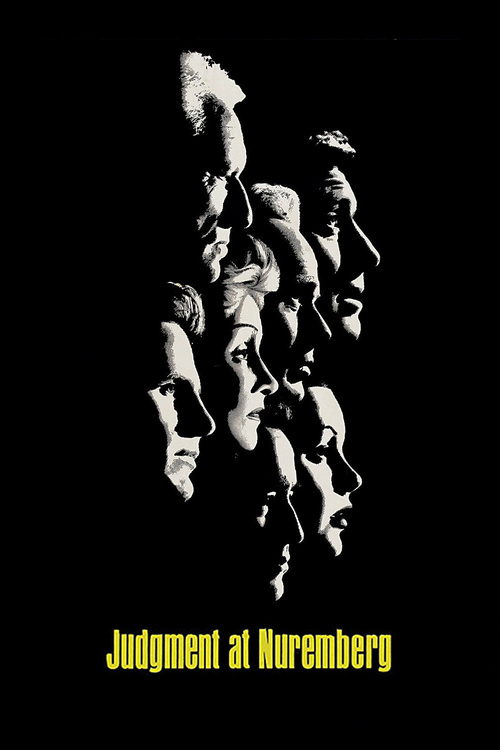

Six years later, her superb dramatic performance in 1961’s “Judgment at Nuremberg” earned her another Oscar nod, but again she was beaten, this time by Rita Moreno for “West Side Story.”

Three more films would follow, but her movie career would end for good in 1963. She’d marry twice more, but both unions were fiascoes, lasting less than a year. She never stopped performing, as she was chronically short of money, all the while dealing with a hostile, intrusive press as well as ongoing struggles with weight, drugs, and depression.

Already in poor health due to liver problems, at age 47, Judy was found dead in London on June 22, 1969. She’d suffered an overdose of barbiturates – the same drug she’d been introduced to all those years ago on the MGM lot.

Her daughter Liza paid for her funeral and her former co-star and lover James Mason gave the eulogy. At her funeral, “Wizard of Oz” co-star Ray Bolger commented, “She just plain wore out.”

Is it any wonder?

When thinking over Judy’s traumatic life, my mind strays to the opening of the tune she was most identified with — “Over the Rainbow.” It’s a beautiful lyric that was cut out of the film.

“When all the world is a hopeless jumble and the raindrops tumble all around… heaven opens a magic lane.

When all the clouds darken up the skyway there’s a rainbow highway to be found. Leading from your windowpane. To a place behind the sun… just a step beyond the rain.”

Judy Garland, here’s hoping you found that place – the magic lane that was always so distant when you were here among us, with so much rain in your life.

Previously: Remembering Mickey Rooney: Hollywood Legend

Didn’t find what you’re looking for? Keep browsing for the right movie to watch tonight on our curated database. Using our search filters, you’ll never spend too much time deciding on a movie again. The best movies to stream are just a click away!