Never a big star but a welcome fixture in westerns and film noirs over three decades, Dan Duryea specialized in playing the heel. In those kinds of parts, no one could touch him.

During the opening titles, if you saw his name just under the leading man’s, you knew you were in for a good time. He was the guy you loved to hate.

And the type of on-screen character he became known for was about as far away from the off-screen Duryea as you could get. In real life, Duryea was a devoted husband and father, an avid gardener and outdoorsman who shunned all the Hollywood hype and decadence, settling with his wife and two sons in the San Fernando Valley.

There he even found time to lead his kids’ Boy Scout troop. As his boys were growing up, Duryea actually forbade them to watch his movies. His simple explanation: “I didn’t want to give them any ideas.”

The actor was nothing if not strategic in his approach to acting: “I looked in the mirror and knew with my puss and 155-pound weakling body, I couldn’t pass for a leading man, and I had to be different. And I sure had to be courageous, so I chose to be the meanest s.o.b. in the movies … strictly against my mild nature.”

Born in 1907 just north of New York City in White Plains, Duryea graduated from White Plains High School and Cornell, where he succeeded future movie actor Franchot Tone as head of the Drama Society. His parents forbade an acting career, so young Dan went into advertising, which he hated. An early heart attack gave him an excuse to leave the business six years later.

At this crucial juncture he decided to follow his passion. Duryea called up his former Cornell classmate Sidney Kingsley, a newly famous playwright whose hit play “Dead End” was still running on Broadway. He started in a bit part at $40 a week, but soon moved up to a featured role. He was on his way.

In 1939, he’d originate the part of Leo Hubbard, a despicable young man who embezzles from his uncle, in Lillian Hellman’s “The Little Foxes.” His aim was to parlay the success of the play into a film contract. As he recalled it: “I suppose a lot of Broadway people will want to kill me for saying it, but I wanted to use Broadway so I could make more money in the movies. Some actors act for art’s sake and starve. That’s not for me. I can’t afford it.”

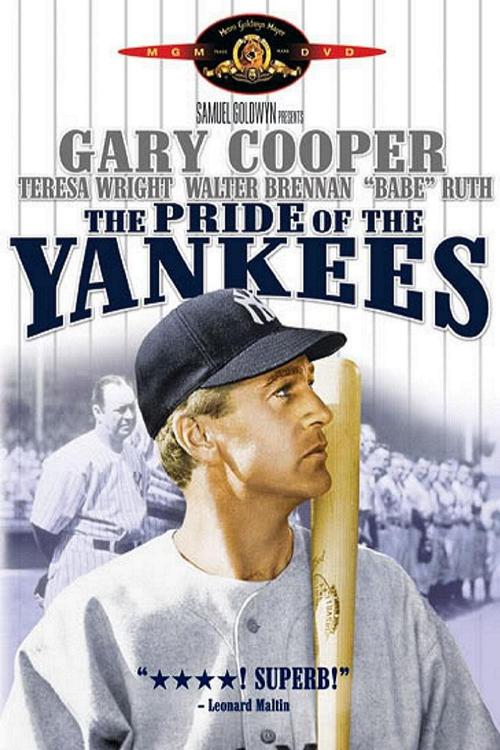

In pursuit of his goal, he signed a contract with Warner Brothers and reprised his breakthrough role of Leo in the screen version of the play starring Bette Davis. Over the next two years, he’d appear in three Warner classics: the hilarious “Ball of Fire,” the Lou Gehrig biopic “The Pride of the Yankees,” and the crackling Bogart war film, “Sahara.”

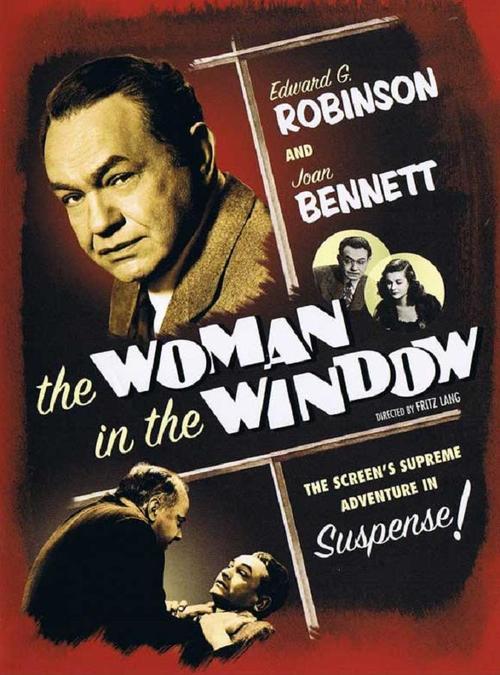

Next Duryea would team with stars Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett and legendary director Fritz Lang for two memorable early noirs: “The Woman in the Window” (1944) and “Scarlet Street” (1945). In the first film, he plays a blackmailer; in the second, an abusive con artist. These roles would cement his lowlife image going forward.

He’d continue appearing in various noir entries over the next few years, some of which hold up very nicely (just check out “Criss Cross” and “Too Late for Tears,” both from 1949). In those rare instances when he took a sympathetic role, it did not go over well with his fan base. He hardly minded.

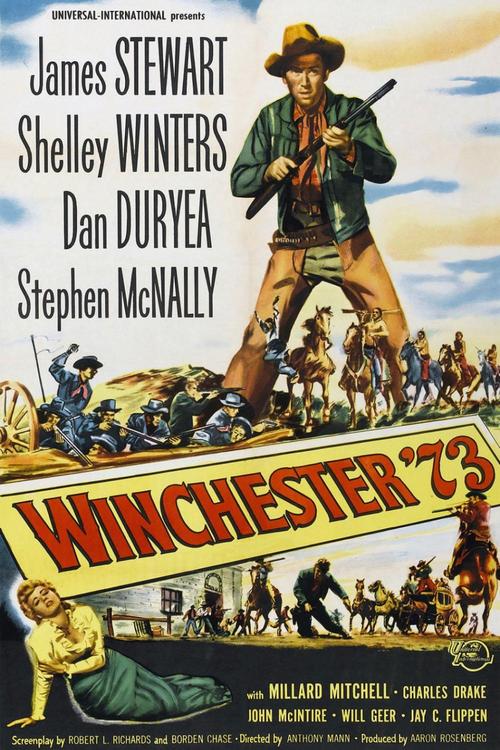

In 1950, he played the villain opposite James Stewart in Anthony Mann’s superb western “Winchester ‘73.” He’d go on to work with Stewart three more times, in “Thunder Bay” (1953), “Night Passage” (1957), and “The Flight of the Phoenix” (1965). On both the small and big screen, Duryea would find a new home in Westerns as film noir faded in the fifties.

The booming new medium of television ensured that Duryea would stay busy as long as he wanted to act. And he chose to keep acting right up to the end. A year after Helen, his wife of thirty-five years, died of heart disease, Duryea himself succumbed to cancer. He was 61.

This gifted actor, who enhanced any film or TV episode in which he appeared, summed up his career this way: “You can’t make a picture without a villain . . . it pays well and you last.”

Dan Duryea, we’re grateful you lasted, and wish you’d lasted a bit longer. You made the bad guys look good.

More: The Man Behind the Mob Boss — The Fascinating Life of Edward G. Robinson