“Dying is easy, comedy-that’s hard.”

Few truer lines were ever spoken. Writers and humorists from Oscar Wilde to Moss Hart to Woody Allen have referenced the eternal mystery involved in isolating just what makes people laugh. An indifferent drama may be survivable, but not an indifferent comedy. There is nothing so deafening as the silence when a joke falls flat.

But oh, when comedy works, what joy. Laughter not only makes us feel good, it comforts us, eases our pain, even extends our lives. It gives us vital perspective on our shared flaws as people, reminding us we’re all fallible. And rather than regret it, we can rejoice in it.

Over a hundred years, from the Chaplin shorts forward, movies have frozen sublime comedic moments for posterity. Here are selected classics from 1925-1950 that are as funny today as when first released.

Out of the inspired visual and physical comedy of the early days came a memorable character that not only amused us but touched us as well. He immediately became the universal underdog, and viewers all over the world took him to their hearts. He was “The Little Tramp,” and Charlie Chaplin gave him life.

The three films that best capture his unique comic genius are “The Gold Rush” (1925), “City Lights” (1931), and “Modern Times” (1936). Falling between his more prolific early work and his more sporadic later films, these are the glittering gems in Chaplin’s Triple Crown.

Before screwball comedies came into their own in the thirties, there was already a phenomenon called “The Lubitsch Touch.” German-born Ernst Lubitsch specialized in souffle-light, sophisticated comedies mostly set in luxurious locales. One of his best outings is 1932’s “Trouble In Paradise,” which features a love triangle between a male and female jewel thief (Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins), and the beautiful heiress who is their latest mark (Kay Francis). If you like your chuckles with a touch of class, here’s your movie.

What can I add to the volumes written about the Marx Brothers? If they didn’t invent comic anarchy, they certainly perfected it…I recommend the early Paramount features, particularly “Duck Soup” (1933), along with their first two MGM outings, “A Night At The Opera” (1935) and “A Day At The Races” (1937). Just sit back and let the inspired lunacy wash over you.

The inspired teaming of William Powell and Myrna Loy gave charmed life to the “Thin Man” series, and certainly everyone should see the first entry (1934’s “The Thin Man”). You should also check out Powell and Loy in the inspired but under-appreciated “Libeled Lady” (1936), co-starring Spencer Tracy and Powell’s then fiancee, Jean Harlow. Powell plays a reporter hired by his former paper to woo the heiress (Loy) who's threatening a libel suit. Stil, my favorite Powell vehicle, made the same year, is “My Man Godfrey,” co-starring the gifted comedienne Carole Lombard (formerly Powell’s spouse in real life, who’d then go on to marry Clark Gable). The story of a butler in a zany household who is not what he seems, “Godfrey” blends screwball elements with more serious overtones on the inherent waste and injustice in our own class structure.

Cary Grant, perhaps the greatest movie star of all time, never won an Oscar because (it was said) he always played himself. Yes, but who else could have played him so well? No one so good-looking ever had such sublime comic instincts. His must-see comedies were made over just three years: “The Awful Truth” (1937), “Bringing Up Baby” (1938), and from 1940, both “The Philadelphia Story,” and “His Girl Friday.”

W.C. Fields, like the whisky he worshipped, is an acquired taste, but once and if acquired, great fun lies in store. Even non-Fields-ians should appreciate his crowning work, “The Bank Dick” (1940), about a henpecked, tippling husband and father who becomes the unlikeliest of heroes. (Also check out four of his short films lovingly compiled by the Criterion Collection, of which “The Dentist” is particularly hilarious.)

Preston Sturges was a brilliant director of comedies in the ‘40’s, filling his off-kilter world with some of the most distinctive stock players in all movies, including that inimitable grouch, William Demarest. Three of his films are particular favorites: “The Lady Eve” (1941), a screwball jaunt set on a luxury liner, starring Henry Fonda (not known for his comedies, but good in this one) and the alluring Barbara Stanwyck; “Sullivan’s Travels” (1942), a brilliant fable starring Joel McCrea about a movie director of silly comedies who wants to make a “message” picture; and finally, “The Palm Beach Story” (1946), where McCrea must head south to win back estranged wife Claudette Colbert from a super-wealthy admirer (Rudy Vallee).

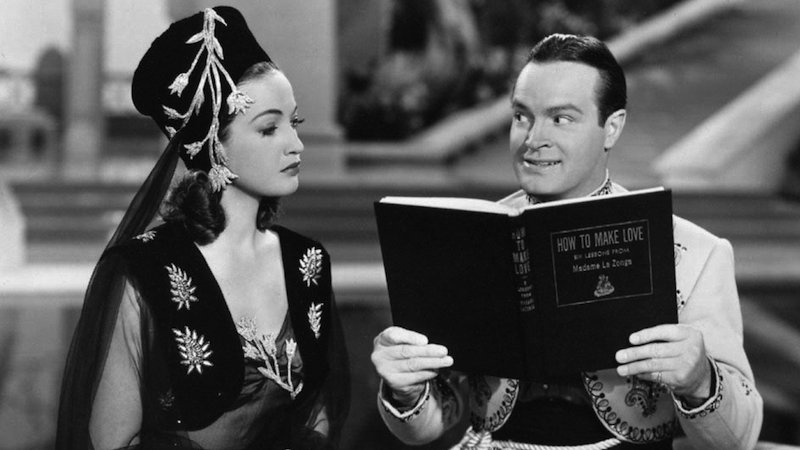

Before the late, great Bob Hope descended into a series of increasingly stale movies in the ‘60’s, he did some extremely solid film work, mainly in the 40’s. Here are two choice titles for your Hope chest: “The Ghost Breakers” (1940), an infectious haunted house comedy, and in my view, the best of the fabled “Road” pictures: 1942’s “Road To Morocco” (with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour).

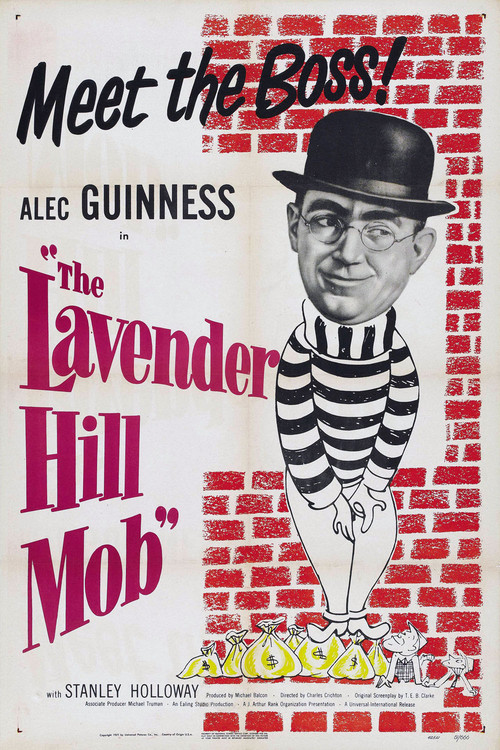

Alec Guinness, best known to most of our progeny as the white bearded sage Obi-Wan-Kenobi in the original “Star Wars,” should be better remembered for his string of terribly British, terribly funny comedies done in the late 40’s/early 50’s with Ealing Studios. Of these, “Kind Hearts and Coronets” (1949) is a must. This ingenious farce concerns one impoverished Duke’s plot to eliminate every cousin standing between him and his (supposedly) rightful inheritance. For dyed in the wool Guinness fans, “The Man In the White Suit” (1951) and “The Ladykillers” (1955), are worthy follow-ups.

I close at mid-twentieth century with three sterling titles. The first is arguably the best of the fabled Tracy-Hepburn pairings, “Adam’s Rib” (1949), about married lawyers facing off in court. This film would introduce the world to the gifted comedienne Judy Holliday. The following year she’d go on to lend new dimension to the familiar dumb blonde stereotype in George Cukor’s “Born Yesterday” (1950), in which Judy plays the moll of a shady businessman (Broderick Crawford) who wants to improve herself. William Holden is hired to help, and romantic complications ensue.

Finally, there is “Harvey,” (1950) perhaps Jimmy Stewart’s signature role. Stewart recreated his Broadway triumph portraying one Elwood P. Dowd, a tippling, benignly imbalanced man with an imaginary friend who just happens to a six-foot tall rabbit. This sweet, gentle, endearing movie was perfectly suited to Stewart’s special gifts. No wonder the actor would often draw a likeness of Harvey the rabbit when asked for an autograph.

These movies add up to over a quarter century worth of laughter. That should hold you for a while.

More: How Movies Got Us Through the Great Depression