“Citizen Kane” is probably the one film that’s been so glorified over the years that many people roll their eyes at its very mention. After all, just who under 40 hasn’t seen it? Even if you haven’t, you’re not likely to admit it.

For over a decade, it occupied the top spot in the American Film Institute’s prestigious Top 100 list. It is a staple of practically every introductory film course on the planet. It has been discussed and analyzed ad infinitum. While so many film classics are worthy of more attention, “Kane” could perhaps do with a bit less.

All this of course doesn’t take away from the fact that it’s still one of the greatest movies ever made.

Its enduring hold on the public also has much to do with the fascinating story of how it was made, how a brilliant but inexperienced 25 year old stage and radio star named Orson Welles came to make it, and the ensuing fallout, which would cripple the rest of Welles’s formerly promising career.

Welles was a child prodigy who by the tender age of 22 had founded his own repertory company with John Houseman in New York: the Mercury Players. Not only was Welles a true theatrical impresario, he was simultaneously pursuing a lucrative radio career, with his mellifluous and versatile voice heard on a variety of programs.

Welles made the cover of Time magazine just after his 23rd birthday. But it would be radio that would launch him to widespread fame just a few months later, when he aired a “War of the Worlds” adaptation that panicked the nation, as listeners tuning in late actually thought the country was experiencing a Martian invasion.

Hollywood had to have a piece of this wunderkind, and began attempts to lure him into pictures with different offers. Welles was in no hurry, and unlike most actors and directors of the day, cared more about creative control than money. The offers kept getting more and more enticing until young Orson had a deal with RKO that was unprecedented for its time: full creative control over the pictures he’d direct, including final cut approval.

Arriving on the West Coast, Welles instantly fell for the magic of making movies and the glamor of Hollywood, while the studio executives realized equally quickly that they may have erred in giving this brash young man so much so soon. Orson would later comment: “I loved it all, but the feeling was not reciprocated.”

When Welles’s first projects were rejected (including an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”), writer Herman J. Mankiewicz presented the idea for “Kane,” and Welles grabbed it. Mankiewicz had based his story primarily on the life of press baron William Randolph Hearst, whom he actually knew.

Welles had no clue how to use a movie camera, much less direct a picture, but here the Gods were on his side. One day Gregg Toland, perhaps the finest cinematographer in Hollywood, approached him.

“I want to work on your picture,” said Toland.

Astonished, Welles said, “This is my first time out. I know nothing about directing a picture. Why would you want to work with me?”

Toland shot back: “For just that reason.”

However, anyone who believes Toland directed and Mankiewicz wrote the film is mistaken. Orson was a very quick learner and had his hand in everything. As he himself admitted, he had the confidence of not really knowing what he was doing, but that very confidence helped produce a work of genius.

Hearst heard about the film late in the game, but still in time to cause trouble. First he tried to buy the print from RKO and have the movie shelved. When that failed, he boycotted RKO from advertising the movie in any of his papers. As a result many exhibitors refused to run it, and the film lost money, even though most critics raved over it.

RKO had gone through hell to make a film that lost money. It promptly renegotiated Welles’s contract so that he’d never have final cut approval on future movies made for the studio. After shooting his next picture “The Magnificent Ambersons”(1942), RKO drastically re-cut it while Welles was safely down in Latin America shooting footage for the war effort. Orson would never speak to his editor Robert Wise again.

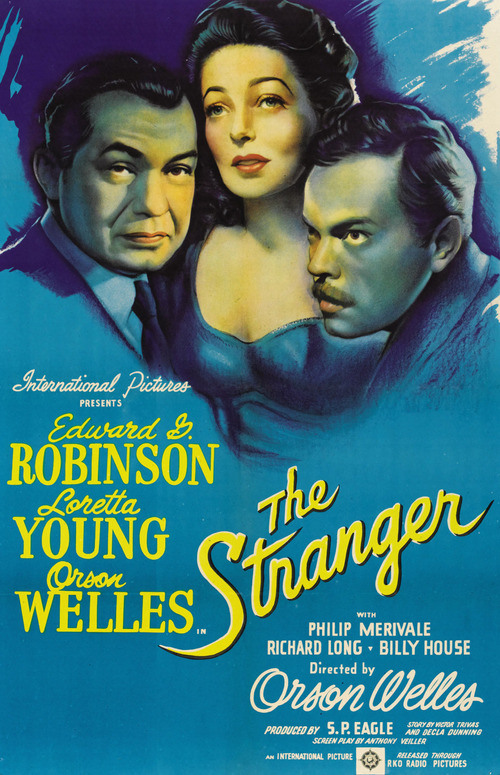

As we all know, Welles would go on to star in several more great films (notably, “The Third Man”) and direct a couple more as well (“The Lady From Shanghai,” “Touch of Evil”). But the studio suits were always looking over his shoulder.

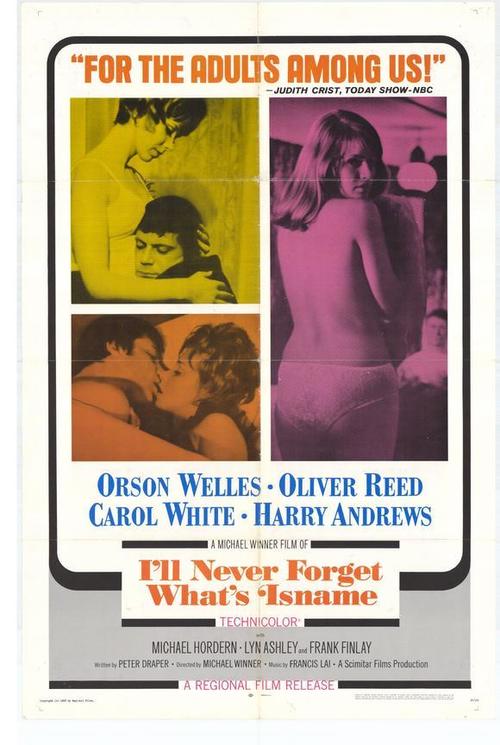

From the fifties on, he’d end up spending most of his time in Europe, raising money for his own projects via film and TV work that was often beneath him, and always searching for backers. Some producers inconveniently went broke in the middle of production, and more than one Welles picture would sit on the shelf, uncompleted.

Yet he never lost his passion or commitment to making films. And though he took a somewhat rueful view of his life and career, he never became truly bitter. He himself summed up his legacy best: “I think I made essentially a mistake staying in movies… but it’s the mistake I can’t regret because it’s like saying, ‘I shouldn’t have stayed married to that woman, but I did because I love her’.”

We love you too, Orson Welles.