In 1910, the prestigious Fred Karno theatrical troupe in England got the chance to tour America. Its star attraction, a twenty-one-year-old performer named Charles Chaplin, was on-board that first ship crossing the Atlantic.

When land was finally spotted, his colleague Stan Laurel, who’d also find fame in the U.S.A, saw Chaplin suddenly race to the railing and shout: “America, I am coming to conquer you! Every man, woman and child shall have my name on their lips — Charles Spencer Chaplin!”

No one witnessing this outburst could have doubted the young man’s determination, but few could have guessed he’d achieve his lofty ambition so quickly and resoundingly.

Within just a few years of landing on our shores, Chaplin had created the character of “The Little Tramp,” and become the most recognized person on the planet. He would play the character in over 70 films, both shorts and eventually full-length features.

Working at studios whose names are now lost to history — Keystone, Essanay, Mutual, and First National — he steadily built up his authority and drawing power as he perfected his wildly inventive art on-screen.

Starting out at Keystone in 1914 under the legendary Mack Sennett, one day Chaplin had the vague idea of assembling a wardrobe based on opposites: a tailcoat and bowler hat that were too small, trousers that were too baggy, and outsize shoes. Then a small greasepaint moustache to add some years, a bamboo cane, a curious waddle for a walk, and voila!

Chaplin said that at first, “I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the make-up made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked onto the stage he was fully born.” He described him later as “a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure.”

There was a lot of Chaplin himself in his on-screen persona: he well understood the plight of being dirt poor and alone. In 1889, he’d been born into dire poverty in London, with a drunk, often absent father and a mother who was in and out of mental asylums for most of her adult life.

Charlie’s grim early existence included stints in the workhouse and attending a school “for paupers.” Fortunately, he had an older half-brother, Sydney, who checked in with him periodically, and years later served as his business manager.

Both his parents had once been musical hall entertainers, and the stage would end up being young Charlie’s salvation. His first big break came in 1903, when he was cast as a pageboy in a touring production of “Sherlock Holmes.” More companies and tours would follow. Then came the opportunity to work for the Karno troupe, where Sydney was already employed.

Fast forward to 1914: Now suddenly rich and famous, Chaplin still could not shake the trauma of his childhood. Long after he could have moved out and up, he chose to live in a shabby hotel room. Deep down, he was terrified that all his newfound wealth would be taken away from him, and that he’d find himself back where he started, in the poor house.

He could be charming on occasion when he was “on,” but more often he was moody, withdrawn and solitary. He also had a volcanic temper. At the same time, he was supremely self-confident, well aware of his own brilliance, and unwilling to trust the judgement of others. He once admitted: “I think a very great deal of myself. Everything is perfect or imperfect, according to myself. I am the perfect standard.”

By the time he co-founded United Artists in 1919 (with fellow industry titans Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D.W. Griffith), he had paid his dues working for others and could now exert full creative control over his movies. This had been his primary goal all along, and he was just thirty when he achieved it.

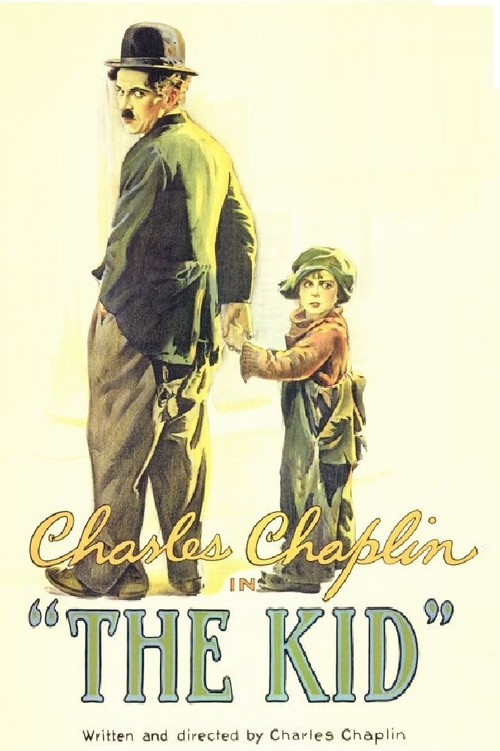

The twenties would take Chaplin to new heights professionally. In 1921, he released his first feature-length film, “The Kid,” where over the course of the picture, the Little Tramp seeks to protect an abandoned child played by the adorable Jackie Coogan. A huge hit on release, “The Kid” signaled Chaplin’s progression beyond pure slapstick to a subtler blend of comedy and pathos.

Charlie’s stature and seemingly unlimited resources meant he could take his time with his movies. He was, admittedly, a perfectionist. For much of his early career, he also shot without a working script, basically experimenting and improvising on-set until he had what he wanted. He would do a hundred takes to get a scene just right, or send everyone on the set home for the day if he was blocked.

After directing his frequent co-star Edna Purviance in “A Woman of Paris” (1923), Chaplin wanted to return to pure comedy and somehow outdo all his previous work. Inspiration came at the home of Douglas Fairbanks, where one day his host just happened to show Charlie some pictures of the Klondike Gold Rush from 1898.

1925’s “The Gold Rush,” where the Little Tramp faces danger and adversity as a prospector, was Chaplin’s most inspired outing to-date. It was also his most ambitious, costing over $1 million to produce- an unheard-of price tag- and taking fifteen months to shoot. The film became one of the silent era’s most profitable films, earning $5 million at the box-office.

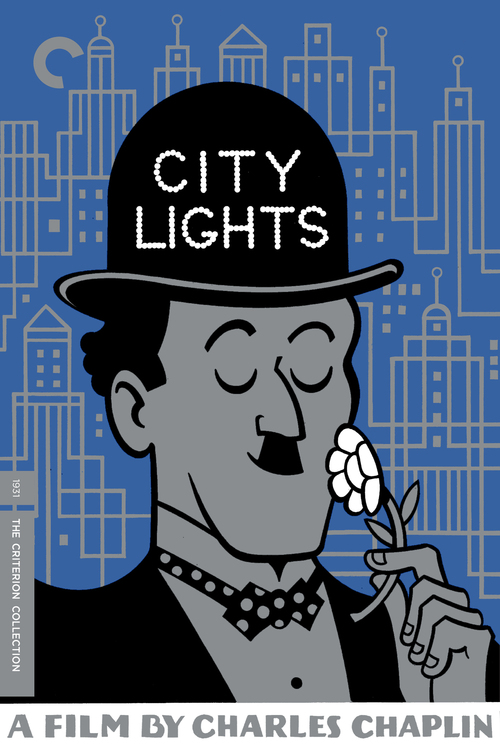

Perhaps not surprisingly, Chaplin resisted the advent of sound pictures two years later, and was the only artist with enough clout to keep making silent films in spite of the industry’s swift transformation to talkies. His biggest gamble on keeping silent came in 1931, when he released “City Lights,” the story of a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill) and the Little Tramp’s efforts to get her an operation to restore her sight.

Charlie, of course, triumphed over all the naysayers, producing a masterwork revered by critics and public alike. Today, “Lights” is considered by many to be Chaplin’s pinnacle, though the lighter, funnier “Gold Rush” is also a contender.

At this point, Charlie took an extended break. He’d earned it, having worked so hard for so long. He was also at a crossroads, feeling doubtful about pulling off another silent film, and ambivalent about making a talkie. In his heart, he felt his “Little Tramp” should stay silent. “Words,” he once remarked, “are cheap.”

For well over a decade, his personal life had been every bit as chaotic as one of his Keystone shorts, though not nearly as wholesome. Before he’d turned forty, he’d been married and divorced twice. His second wife, Lita Grey, was slated to star in “The Gold Rush,” but Chaplin had impregnated her, forcing a trip to the altar. She was 17. (Chaplin’s first marriage to another teenager, Mildred Harris, had occurred under the same conditions).

Though he had no surviving children with Harris, Grey bore Charlie two sons in quick succession, and their eventual divorce in 1927 was particularly nasty and public. After “City Lights,” all that was in the rear view mirror. Chaplin found himself not only free but with time on his hands. Then he met an aspiring actress named Paulette Goddard.

Paulette was different from the ladies that had come before: a bit older (thankfully), tough, pragmatic and career-focused. Charlie admired her drive, and took her under his wing. He coached her extensively, and suggested she lose her platinum blonde hairdo and go back to being a brunette. They would finally marry in 1936.

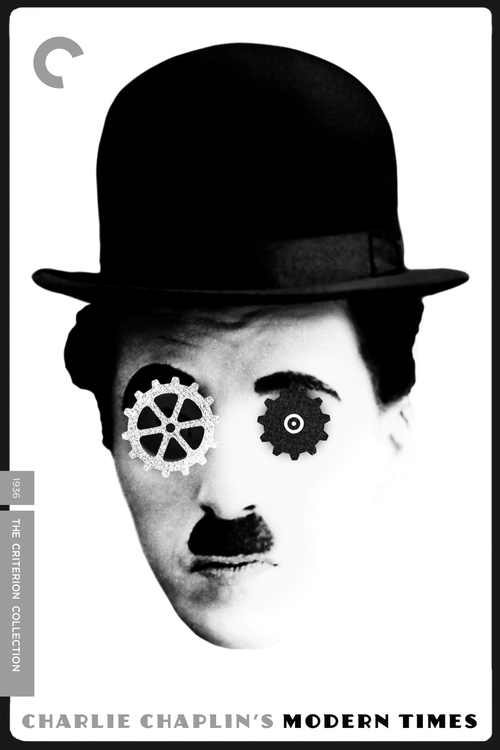

By this time, they had collaborated on his long-awaited next picture, “Modern Times,” a silent film (this time out, with sound effects), which Chaplin described as “a satire on certain phases of our industrial life.”

Considered a classic today, on release the film earned mixed reviews and box office returns not up to his prior films. Some critics took Chaplin to task for his thinly veiled political and social commentary. “Times” would also mark the Little Tramp’s final appearance on-screen.

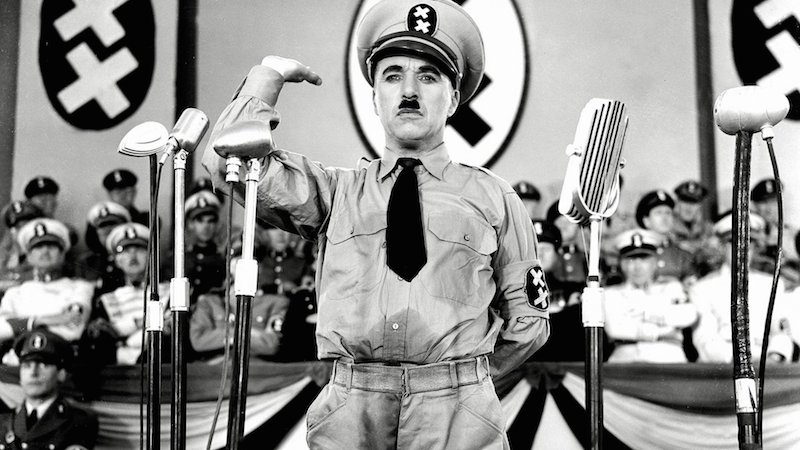

Now pushing fifty, Charles Chaplin entered a new phase of his life, making only five more pictures over the four decades left to him, including his anti-Fascist “The Great Dictator” (1940), the black comedy “Monsieur Verdoux” (1947), and his bittersweet on-screen swansong, “Limelight” (1952), where Charlie plays a clown long past his prime.

He had divorced Paulette Goddard in 1942, and the following year married eighteen-year-old Oona O’Neill, daughter of famed playwright Eugene. This marriage would endure, yielding eight more children for Chaplin. In the coming years, Oona would become virtually his only bright spot, and he would rely heavily on her for emotional support.

Charlie had been vocal in his admiration for our Russian allies during the Second War, and as a wave of anti-communist paranoia swept over the country in the late forties, he found himself under attack, his loyalty questioned. The FBI opened a case file, exhuming his messy, inappropriate past relations with underage women as potential cannon fodder.

Chaplin knew when to make an exit, and would leave his adopted home for good in 1952; over his forty-plus years in residence he had never become an American citizen. He settled with Oona and his growing family for a quiet retirement in Switzerland.

As time passed, stateside attitudes towards Chaplin inevitably softened. In 1972, he was finally invited back to receive an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement. As the small, white-haired man took the stage to receive the award, the audience stood and clapped for a full twelve minutes. It still stands as the longest ovation in Academy history.

In keeping with his legacy, Chaplin had very few words yet conveyed tremendous emotion. Visibly moved, he basked in the love and gratitude of millions that he thought he would never feel again. He said: “Thank you so much. This is an emotional moment for me. Words seem so futile and so feeble. I can only say thank you for the honor of inviting me here and you are all wonderful, sweet people. Thank you.”

No, thank you, Charlie Chaplin, for all the laughter and all the tears. Thank you.