It always irked Gene Kelly that dancing was considered an effeminate activity for men. When his mother first enrolled him and his brother in dance classes when Gene was still a boy, he had to endure taunts from his classmates which he promptly settled with his fists.

Years later, the prodigiously gifted Kelly would quit a successful career heading a dancing school in his native Pittsburgh because among his students, the ratio of males to females was ten to one.

Turning to full-time performing at the age of 25, he was already shaping his own distinctive, highly masculine style of dance, one that would blend a variety of styles, including ballet, and showcase his natural athleticism.

Of course it was inevitable that he’d be compared to his idol, Fred Astaire, but Gene’s approach was very different, which actually served the careers of both men well.

Asked to differentiate himself from Astaire, he said: “I work bigger. Fred’s style is more intimate…the sort of wardrobe I wore — blue jeans, sweatshirt, sneakers — Fred would never have been caught dead in. He was always immaculate at rehearsals, while I was always in an old shirt. Fred’s steps were small, neat, graceful and intimate where mine were ballet-oriented and athletic.”

Both men shared not just a mutual admiration, but a grueling work ethic and intense pursuit of perfection. This was already evident in the Broadway play that truly launched Kelly’s career: 1940’s “Pal Joey.”

As co-star Van Johnson recalled, “I watched him rehearsing, and it seemed to me that there was no possible room for improvement. Yet he wasn’t satisfied. It was midnight and we had been rehearsing since eight in the morning. I was making my way sleepily down the long flight of stairs when I heard staccato steps coming from the stage…I could see just a single lamp burning. Under it, a figure was dancing…Gene.”

In 1942, Kelly was lured to Hollywood by the legendary David O. Selznick for a one picture contract. The picture turned out to be 1942’s “For Me and My Gal,” his first outing with Judy Garland, and the contract (bought from Selznick by MGM’s Arthur Freed) was extended.

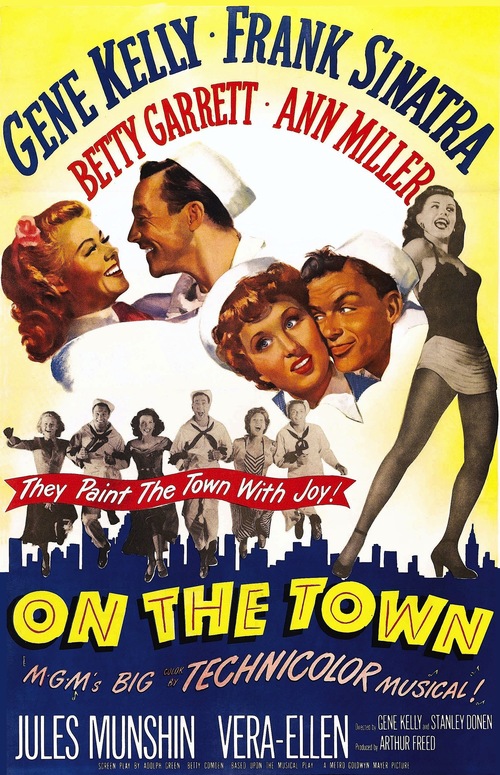

By the time he made “On the Town” (1949) his first of three collaborations with Stanley Donen, he’d already earned a Best Actor Oscar nod for 1945’s “Anchors Aweigh,” his first pairing with the then-skinny Frank Sinatra. (This distinction was virtually unheard of for a “hoofer”; Astaire’s only Oscar nomination would come fifteen years later for a straight dramatic role, in 1959’s “On the Beach”).

WHEN YOU WALK DOWN MAINSTREET WITH ME FROM “ON THE TOWN” (1949)

Like “Aweigh,” “Town” also involved sailors on leave, but this time out, Kelly had Donen to co-direct, a buoyant script from Betty Comden and Adolph Green, a Leonard Bernstein score, and the ability to shoot on-location in Manhattan (rare for a musical). The film, of course, was a huge hit.

But Gene had yet to reach his pinnacle. In 1951, MGM decided to produce a musical based on the Gershwin songbook called “An American in Paris.” A first class team was assigned: Vincente Minnelli would direct, and Alan Jay Lerner would write the script.

Cast in the starring role, Kelly lobbied hard for an unknown French dancer and actress named Leslie Caron to co-star. The main female character would be French, after all, and he wanted authenticity. Rounding out the players were Oscar Levant (who’d actually known the Gershwins), Nina Foch and Georges Guetary.

WITH LESLIE CARON IN “AN AMERICAN IN PARIS” (1951)

The film was a sensation on release, featuring a breathtaking eighteen-minute ballet sequence that’s justly famous to this day. At the 1952 Oscars, it won six Oscars and became only the third musical in the Academy’s twenty-five-year history to win Best Picture. Kelly himself was given an honorary award “in appreciation of his versatility as an actor, singer, director and dancer, and specifically for his brilliant achievements in the art of choreography on film.”

Meanwhile he’d already reunited with Stanley Donen to co-direct “Singin’ in the Rain,” the film he’d be best remembered for. A spoof of Hollywood during its transition from silent to sound pictures, the movie came out just a week after the Oscar ceremony. It did well at the box office but initially failed to generate the stunning critical reception afforded its predecessor, with Bosley Crowther of the New York Times dismissing “this song-and-dance contrivance” as “an impudent, offhand comedy.” Nominated for two Oscars, it did not win a single statuette.

SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN FROM “SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN” (1952)

Its reputation has, of course, grown over the years. Many consider it to be the best musical ever, and it is certainly the funniest. The American Film Institute ranked it as the fifth best movie ever made.

As the fifties progressed, big budget musicals started falling out of favor. Gene would stay busy but never achieve the same level of acclaim again. He grew increasingly frustrated with MGM, particularly when they refused to lend him out to play Sky Masterson in “Guys and Dolls” (1955), or the title role in “Pal Joey” (1957), which he’d originated on Broadway. (Ironically, his old colleague Frank Sinatra would appear in both those films). Gene did a few non-musical roles, most memorably playing a cynical reporter in the courtroom drama, “Inherit the Wind” (1958).

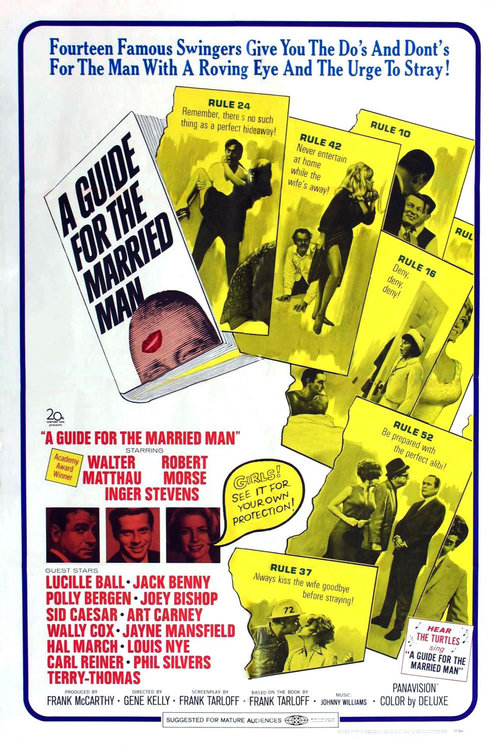

Having co-directed features twice with Donen, he became eager to spend more time behind the camera, helming the sex farce “A Guide for the Married Man” (1967), the film version of “Hello Dolly” (1969), and “That’s Entertainment — Part 2” (1976), in which he also appeared. His last film role was in the musical “Xanadu” (1980) opposite Olivia Newton-John, which he kindly described as a good idea that just didn’t come off.

Ill health plagued Gene starting in the late eighties, and on February 2, 1996, he passed away after a series of debilitating strokes. He was 83.

Asked to sum up his career, Kelly replied: “I took it as it came and it happened to be very nice.”

It was very nice for us too.