It is sad and somewhat perplexing that while James Dean has become an enduring icon, Nicholas Ray, the director that mentored and influenced him, is nearly forgotten.

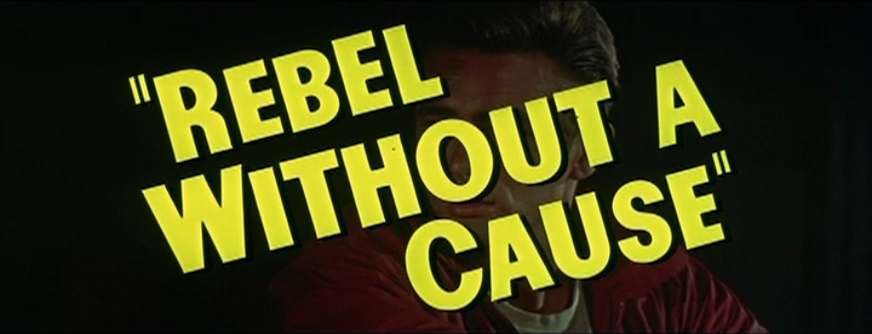

In early 1955, Jimmy (as he was widely known) had just wrapped his first major film, Elia Kazan’s “East Of Eden.” Kazan’s old friend Nick Ray was slated to shoot “Rebel Without A Cause,” about the phenomenon of gangs and rebellion among America’s teenagers. It would be shot in black and white, strictly a “B” picture.

Even though Kazan warned his colleague against using the difficult, temperamental Dean, Ray knew he’d be perfect for the starring role of Jim Stark, a troubled youth from comfortable circumstances who finds his dysfunctional parents and small town, middle class existence unbearably stifling.

Dean signed on, but was at first ambivalent about his new director. He had greatly respected Kazan, but Ray seemed — and was — more erratic, not quite on the same footing with the man who’d helmed the prior year’s instant classic, “On The Waterfront.” In addition, Jimmy was experiencing sudden fame, and figuring out how to cope with it. So — just as shooting on “Rebel” began, the star took a powder.

Both Ray and the Warners Studio were frantic, but soon enough, Dean was found and coaxed back. By this time, the early returns on “Eden” confirmed they had a major new star on their hands and Warner’s had upgraded the production to widescreen color. To take full advantage of this, Dean’s brown windbreaker was scrapped and replaced by a vibrant red one. That jacket would become iconic.

It was a fascinating and eventful production. Dean’s co-star was Natalie Wood, at 18 an old Hollywood veteran and former child actress who’d fought hard for her first adult role. Her sexuality was budding, and soon she was having an affair with her 43 year-old director. Next Natalie would go on to have a fling with a young Dennis Hopper who was also in the cast. Wood’s protective mother, Maria Gurdin, was aware of both liaisons, but ever mindful of her daughter’s career, decided only to complain about Hopper. (The young actor was understandably resentful but later buried the hatchet with Ray.)

Then there was the presence of Sal Mineo, who played Stark’s sensitive friend, Plato. Ray fully intended that the audience infer that his character was gay, but the Hollywood Production Code was still in force back then, so the clues would have to be subtle. At one point we see a photo of Alan Ladd in Plato’s locker, and Plato gazes longingly at Jim more than once. Reportedly, at one point Dean told Mineo: “Look at me just the way I look at Natalie.” Given Jimmy’s smoldering good looks and Sal’s own sexual orientation, this would not prove difficult.

When Ray called “Cut!” for the final time, both cast and crew were sorry to move on, sensing correctly they’d been part of something special. Then, several months later, roughly a week before the film’s premiere, James Dean was killed in a car crash.

The world was stunned and sorrowful, but Nicholas Ray was crushed. He and Dean had bonded over all they had in common: both had grown up without fathers; both had reckless, self-destructive streaks; both were loners at heart. The two had planned to form a production company together, which would have given Ray continual access to Hollywood’s brightest young star, and importantly, provided a buffer against the studio control and interference he so hated. In an instant, that promising, exciting future was gone.

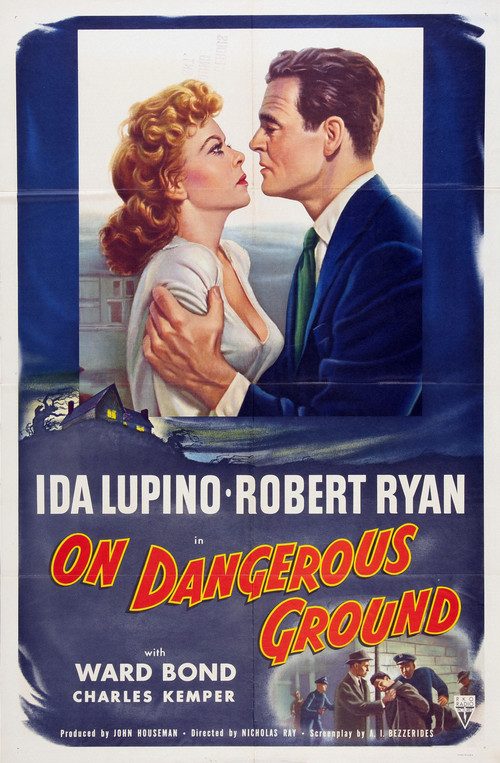

“Rebel” opened to generally positive notices and was a hit at the box office. At Oscar time, Wood, Mineo and Ray were all nominated (Ray for his original story). Still, with the death of James Dean, whatever good fortune and talent Nick Ray had possessed seemed to dry up. Beset by personal demons, including addictions to alcohol and gambling, Ray’s directing career was over within just a few years. Though he was briefly re-discovered in the mid-’70s, there would be no real comeback. His health broken and nearly destitute, he died in 1979 at age 67.

“Rebel” would become known as his crowning achievement. Even in his saddest, darkest moments, Nicholas Ray could look back on all he did up to that point in 1955 when all hope vanished on a lonely California highway. In a very real sense, James Dean was not the only one who died that day.