Though successful on release, this indelible classic from 1942 truly entered the zeitgeist in the late 50’s and early ‘60s, when a whole new generation of viewers, specifically Harvard students, fell in love with it.

The Brattle Theatre in Cambridge had brought back the film in 1957, and it had done amazing business. After that, the management resolved to run it every year during final exams. It was then that seeing “Casablanca” there became a rite of passage — and an annual tradition — for Harvard men (and Radcliffe women).

The film’s enormous popularity spread from there, and has never really faded. Today, “Casablanca” is routinely ranked by respected sources as among the top 5 movies ever made.

It deserves its place on those lists. With the vast majority of it shot on a Hollywood soundstage, “Casablanca” still delivers breathtaking romance amidst the tumult of a world engulfed in war.

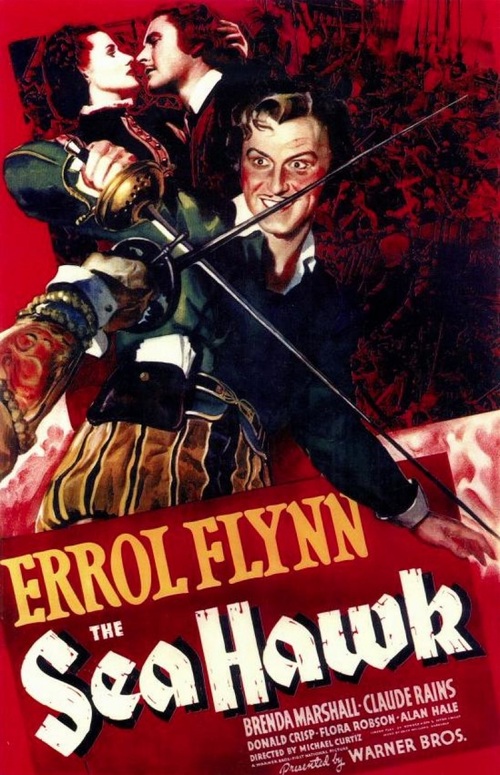

The film feels startlingly European, and there are several reasons for that. Beyond the fact it was shot by one (director Michael Curtiz was Hungarian), all but three of the principal cast were European. Many Nazi roles were filled by Germans who’d actually fled Germany, including Conrad Veidt who plays the menacing Major Strasser. Veidt was an outspoken anti-Fascist whose wife was Jewish.

Given “Casablanca”‘s enduring impact on the popular culture, it’s striking how low expectations were for the film, proving John Gregory Dunne’s old saying that in Hollywood, “nobody knows anything.”

The movie started out as an unproduced play called “Everybody Comes To Rick’s,” which Warner Brothers purchased for the then-princely sum of $20,000. It’s likely the only reason the play was even picked up was that it was received literally the day after Pearl Harbor, when word had already gone out that the studio wanted to produce patriotic stories.

Still, it would be just another picture on the Warner Brothers roster, to be shot for under a million dollars.

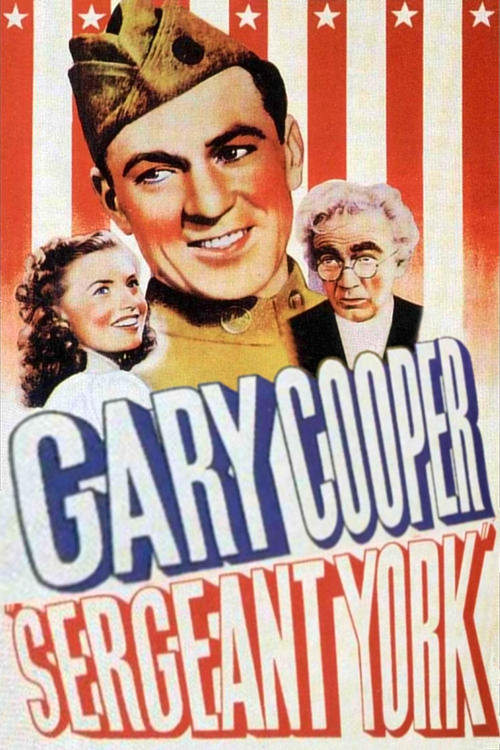

Hal Wallis, Warner’s head of production always saw Humphrey Bogart in the lead, even though the more established George Raft was lobbying for the role after first turning it down. (Raft’s bad career choices were largely responsible for Bogart becoming a star at age 40 — he’d already turned down the leads in both “High Sierra” and “The Maltese Falcon.”)

Screenwriters Julius and Philip Epstein felt rising star Ingrid Bergman would be ideal for the central role of Ilsa. They lobbied producer David O. Selznick , who held her contract, to lend her to Warner’s. Bergman herself didn’t want to do it; she was not sold on the story, and wanted her next picture to be Ernest Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” (She would end up doing it after “Casablanca”).

Paul Henreid, cast to play the heroic Victor Laszlo, was even angrier about having to make the film. He thought taking third billing after Bogart and Bergman would hurt his career as a romantic leading man. He’d just starred opposite Bette Davis in “Now, Voyager”; this was definitely a step down. Reportedly, he pouted during most of the shoot.

It’s amazing that Bogart and Bergman generated so much screen chemistry, as they had very little in person. The dutiful, disciplined Ingrid had watched “The Maltese Falcon” over and over again to get a sense of her co-star, but she could never break through with him on the set. She had a line right out of a movie to describe their relationship: “I kissed him, but I never knew him.”

Part of the issue may have been Bogart’s discomfort at having to romance a beautiful woman a couple of inches taller than he was. Bogie was relatively new to leading man status, having spent most of his career playing gangsters who get shot in the final reel. He may well have been secretly cowed by the vision of this tall, stunning Swedish woman; many men would have been. And having to wear platform shoes to boost his height in love scenes was not exactly an ego boost for this notoriously prickly actor.

Ingrid herself was frustrated at not knowing how the picture would end. The Epstein brothers were struggling with this well into the shooting schedule. When Bergman told Curtiz that she could shade her performance by knowing whom she’d end up with, he responded cryptically, “Just play it in-between.”

Miraculously, out of all this awkwardness and bad feeling a masterpiece emerged. The film was nominated for eight Oscars, and won three, including Best Picture. The stars, who’d always felt the story was incredibly hokey, must have been stunned. The studio brass, however, had their instincts borne out- they’d seen the rushes as production progressed, and sensed a hit.

But likely no one could have foreseen how influential and beloved this film would become once a crowd of college students took it to their hearts roughly twenty years later.

Here’s looking at you, Casablanca.

More: Here’s Looking At You, Kid — A Brief History of How Bogart Became Bogart