If the stunningly talented, charismatic Barbara Stanwyck was hurt by not having picked up that coveted statuette over the course of four Best Actress nominations, she never showed it. And she wouldn’t have. She was too tough and too proud for that. And yes, I mean that as a compliment.

She was born Ruby Stevens to a working class family in Brooklyn in 1907. Tragedy struck early: when Ruby was just four, her mother was killed after a drunk knocked her off a trolley car. Her grieving father was simply unable to cope. Without a word, one day he vanished. (It’s believed he took a job on the Panama Canal; regardless, he never came back.)

Ruby and her closest brother Byron were then separated and shunted off to various foster homes. One can only imagine the misery and loneliness she experienced during this period.

Show business would be Ruby’s salvation. Her much older sister Mildred had become a showgirl, and Ruby was permitted to visit her on tour. She was immediately drawn to the heady buzz of the stage; the audience, bright lights and backstage bustle held only wonder and excitement for her.

After working briefly for a telephone company, she finally won a job as a chorus girl at the age of 16. Petite but with a stunning figure and seductive eyes, she soon won a plum position in the prestigious Ziegfeld Follies.

After several years as a showgirl, Broadway beckoned. Her ascent was swift: after making her debut in 1926, she won the lead part the following year in a hit play called “Burlesque.” Ruby was on her way — actually Barbara Stanwyck was, as by this time, she’d changed her name.

Fifteen years Barbara’s senior, in 1927 Frank Fay was a veteran stage performer at the peak of his fame. When Stanwyck met him, she was wowed by his charm and force of personality. She could hardly believe a star of his magnitude could be interested in her. Romance blossomed as he took her under his wing, becoming her guide and mentor. They married in 1928.

At this point, Fay had his sights set on a Hollywood film career, and Barbara hoped for the same. Moving to L.A., the story that many claimed would inspire the film “A Star Is Born” played out: the older, established actor failed to score on the big screen and took increasing solace in the bottle, while his young wife rose steadily as a star by dint of raw talent, determination, and hard work.

After Fay’s drinking caused him to turn abusive, threatening not just Barbara but their adopted son Tony, she finally left for good and divorced Fay in 1935. The following year, she made a film called “His Brother’s Wife,” and fell for her handsome co-star, Robert Taylor. Four years older than newcomer Taylor and already a seasoned Hollywood player, Barbara played the mentor this time around, and he the eager pupil. Initially skittish about getting remarried, she finally yielded, and the couple wed in 1939.

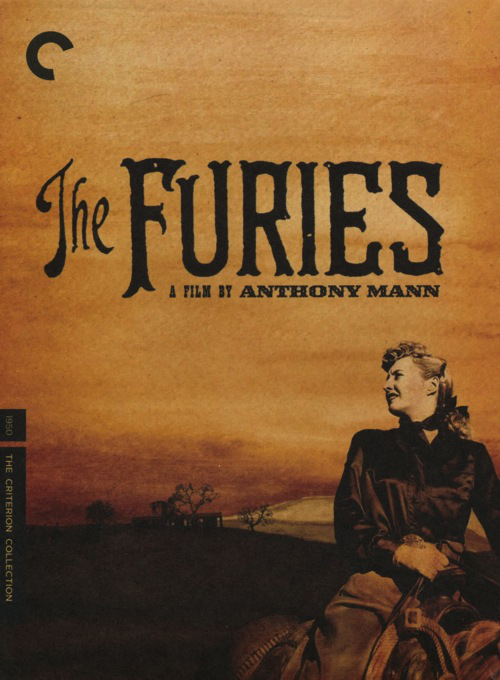

Meanwhile, Barbara’s film career was flourishing. Beyond her natural beauty, audiences related to the honesty and feeling she brought to every role. She was totally authentic, and a feminist before the word was coined, usually playing women of humble origins who had to fight to achieve their proper place in the world. As an actress, she was also amazingly versatile, equally skilled at comedy or drama, westerns or suspense pictures.

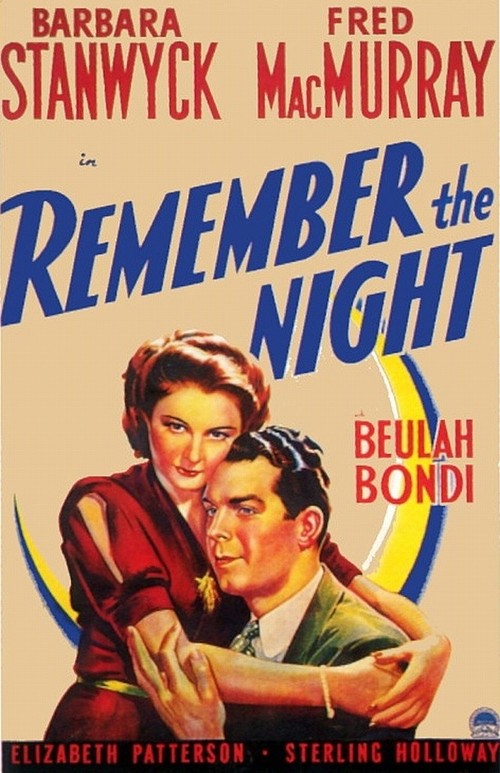

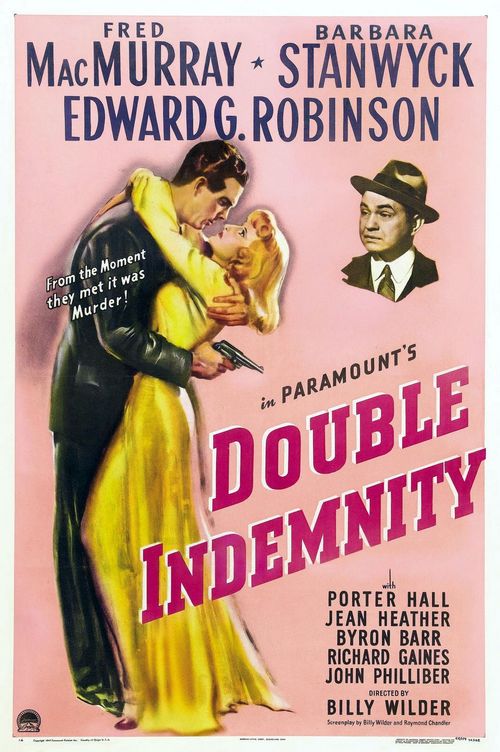

Most memorably, she played a card shark in “The Lady Eve” (1941), a chorus girl on the lam in “Ball of Fire” (1941), a scheming man-eater in “Double Indemnity” (1944), and a bedridden wife in mortal danger in “Sorry, Wrong Number” (1948). She was Oscar-nominated for these last three films, having received her first nod for 1937’s “Stella Dallas.”

Stanwyck gained a reputation in the business for being at once thoroughly professional and unusually generous. A hater of “phonies” and an admirer of regular working people, she made an effort with all the crew members, learning their names and treating then with respect.

Her kindness extended to co-stars as well. She fought hard to keep a young and green William Holden for being fired from the production of “Golden Boy” (1939). Forty years later, he would thank her publicly for it (at the 1978 Oscars). The ever-fragile Marilyn Monroe would also claim that Barbara was the only star from the prior generation who was nice to her.

After World War 2, Robert Taylor had returned from serving in the Naval Air Corps with a strong desire to get some distance from the Hollywood rat-race. Though Stanwyck was initially supportive, in the end she loved to work, and gradually this issue drove a wedge in the marriage. They’d finally divorce in 1952. (Still, their parting was amicable enough that a dozen years later, they’d reunite to make a limp William Castle thriller called “The Night Walker.”) Barbara would always refer to Taylor as the love of her life.

Pushing fifty and with movie roles starting to dry up, she kept busy working in the growing medium of television. Her biggest and most enduring success came in 1965, playing matriarch Victoria Barkley in the Western series, “The Big Valley.” The show lasted five seasons. In a gesture of reverence and respect, the credits featured her as “Miss Barbara Stanwyck.” It seemed totally fitting.

Miss Barbara Stanwyck (whose nickname was in fact “Missy”) kept right on doing what she did best and loved most — acting — till she was nearly 80. A lifelong smoker, she died of emphysema in 1990, at the age of 82.

In 1982, Barbara had received a long-overdue honorary Oscar. After a prolonged standing ovation, she was typically direct, modest and gracious in her acceptance speech, deflecting the honor off herself, and thanking all the people behind the scenes who’d made her look good over the years.

She then concluded her remarks with great poignancy. Referring back to her old friend Bill Holden, who’d died several months earlier, she said: “He always wished that I would get an Oscar and so, tonight, my golden boy, you got your wish!”

This self-deprecating star loved to refer to herself as a “tough old broad from Brooklyn.” Wherever she is, I hope she won’t mind my stating what was always an open secret: On-screen and off, Barbara Stanwyck was a real class act.