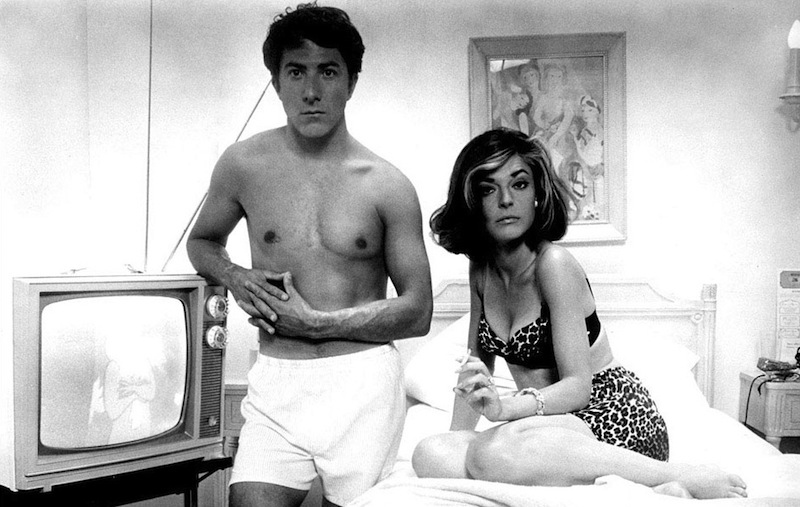

In the years after the smashing success of Mike Nichols’s “The Graduate” (1967), Anne Bancroft came to believe that her portrayal of Mrs. Robinson, the bored middle-aged wife and mother who seduces newly minted college grad Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), overshadowed the rest of her career.

Still, Bancroft understood why her most famous performance struck a particular nerve with the public. As she put it: “I gave a voice to the fear we all have: that we’ll reach a point in our lives, look around and realize that all the things we said we’d do and become will never come to be — and that we’re ordinary.”

It was a great part, beautifully played, but Anne Bancroft had good reason to feel ambivalent about it, as it did deflect attention from some other excellent work she did over the years. (This was precisely how Ingrid Bergman felt about “Casablanca”).

All the more reason to take a closer look at the life and legacy of Anne Bancroft.

She was born Anna Maria Louisa Italiano in 1931, the middle of three daughters. Her parents were working class Italian immigrants who’d settled in the Bronx, where Anne grew up. She was drawn to acting early, and described her particular talent this way: “I can sit with anybody in a room for an hour, and by the time they leave, automatically I will know the way they talk and the way they move. That’s my special art.”

After high school, she studied in several top-flight acting programs, including the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and the Actors Studio. She started working in radio, and then graduated to the emerging medium of live television, where she was billed as Anne Marno.

In 1952, Twentieth Century Fox signed her to a contract, and quickly advised her that the name “Marno” sounded too ethnic. She was given a book of appropriate last names, and she chose “Bancroft” because it had a dignified ring to it.

However, the roles she got through Fox in those years did not dignify her talent. The studio really didn’t know what do with her. As she explained it, “When I arrived in town, the movie industry was looking for sexpot glamor girls. I didn’t qualify. Nor was I ever offered a top-flight movie.” Frustrated after five years of forgettable parts, Bancroft decided to make a break and return home to New York, and the Broadway stage.

It was an inspired move, perfectly timed. Just then a young director named Arthur Penn was casting a play by William Gibson called “Two for the Seesaw,” about a girl from the Bronx who meets and falls for an older man whose marriage is on the rocks.

Penn ended up casting Bancroft as the girl opposite Henry Fonda, and she’d go on to win her first Tony Award for Best Featured Actress of 1958. Just as important, she’d found a champion in Arthur Penn, who once said of her: “Annie’s a very gutsy girl. I swear I wouldn’t hesitate to put her in at shortstop for the New York Yankees.”

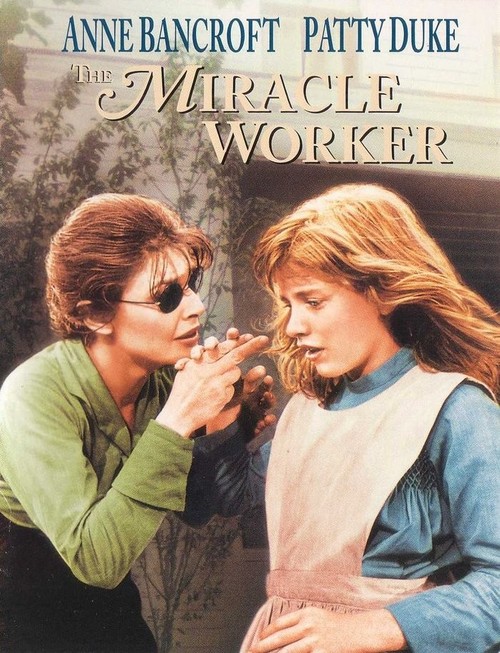

Playwright Gibson had previously written a teleplay called “The Miracle Worker”, about the early life of Helen Keller. It had aired on TV in 1957 with Teresa Wright playing Keller’s teacher, Annie Sullivan. Now he and Penn had the idea of turning it into a Broadway play. This time they had a different actress in mind for Sullivan: Anne Bancroft.

Premiering in October, 1959, “The Miracle Worker” became another big hit, winning Tony Awards for Best Play, Best Director for Penn, and Best Leading Actress for Bancroft. Now, inevitably, Hollywood came calling.

United Artists wanted Penn and Gibson for the film, but not Anne Bancroft. The studio offered to boost the budget if they would agree to cast Elizabeth Taylor or Audrey Hepburn as Annie. The men refused, insisting on Bancroft. Both she and co-star Patty Duke would reprise their Broadway roles in the film, with the budget reduced accordingly.

The resulting film was every bit as successful as the play had been. Having left Hollywood disillusioned and without fanfare five years prior, Anne Bancroft was back in a big way. At the 1963 Academy Awards, she walked away with the Oscar for Best Actress, beating out such luminaries as Katharine Hepburn and Bette Davis.

Her personal life was also on the upswing by this point. After one failed marriage and a string of romances that went nowhere, Anne met comic writer and performer Mel Brooks when the two appeared together on the Perry Como Show in 1961. They clicked immediately, and with Brooks first marriage over, he and Bancroft finally wed in 1964.

They would stay together for over forty years, and have one son, Max, in 1972. About her second husband, Anne once said, “When he comes home at night and I hear his key in the lock, I say to myself, ‘Oh good! The party’s about to begin!’”

In late 1966, director Mike Nichols started casting “The Graduate,” a darkly humorous tale of a disillusioned college graduate who stumbles into an awkward affair with an older woman; even more awkward is the fact that the lady is a close friend of his parents.

Initially, he had French actress Jeanne Moreau in mind for the seductress, Mrs. Robinson. He also badly wanted the folk rock group Simon and Garfunkel to do the soundtrack. The producers, however, were vehemently against both ideas.

Ultimately Nichols had to lose Moreau to keep Simon and Garfunkel, whose anthem to Mrs. Robinson had, prior to the film, been addressed to Mrs. (Eleanor) Roosevelt. However, in losing Moreau, he gained Anne Bancroft. And he’d end up feeling grateful for that, though he’d also considered (among others) Patricia Neal and Doris Day, who was offended by the sex scenes.

Bancroft’s iconic performance would bring her third Oscar nomination (she’d been tapped a second time in 1964 for Jack Clayton’s marital drama, “The Pumpkin Eater”). As convincing as she was playing a sexually frustrated woman in her mid-forties, she was in fact only 36, just six years older than Dustin Hoffman and eight years older than her on-screen daughter, Katharine Ross.

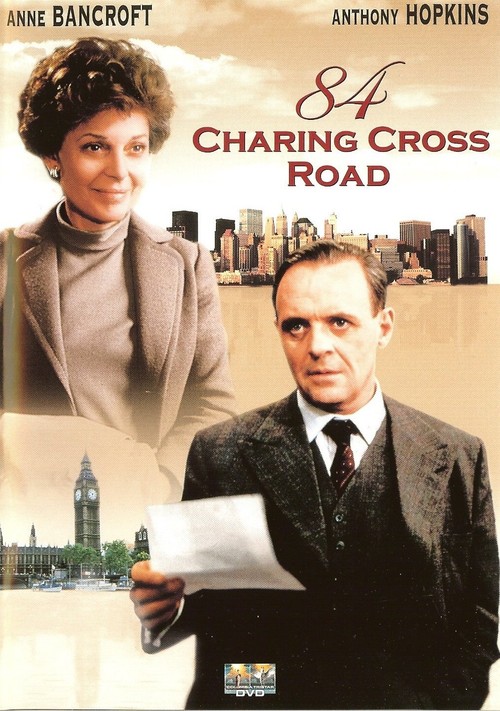

Over the next three-plus decades after “The Graduate,” she would make about forty more pictures. She’d appear on-screen with her husband three times over that period, in “Silent Movie” (1976), “To Be or Not to Be” (1983), and in a 2004 episode of “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

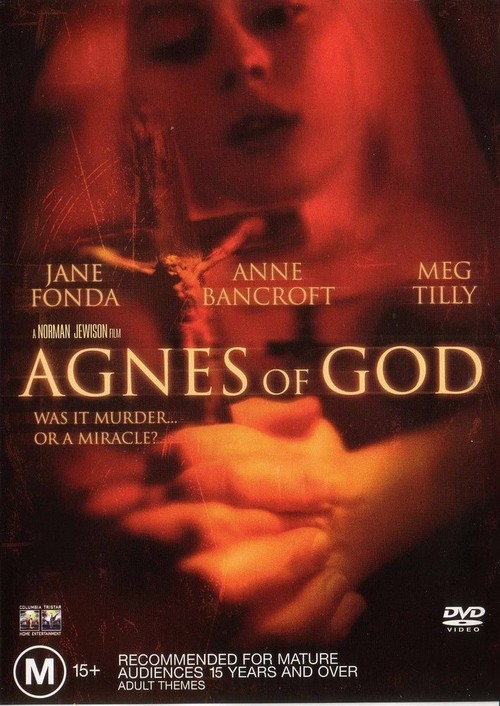

She won an Emmy for a TV special called “Annie: The Women in the Life of a Man” (1970), earned another Tony nomination playing Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir in “Golda” (1977), and even gave directing a shot with 1980’s “Fatso”, co-starring Dom DeLuise, which she also co-wrote. She also racked up two more Oscar nods, for “The Turning Point” (1977) and “Agnes of God” (1985).

When she passed away from uterine cancer in 2005, her friends and public were shocked, since the famously private Bancroft told virtually no one that she was ill. A grief-stricken Mike Nichols released this statement shortly after her death: “Her combination of brains, humor, frankness and sense were unlike any other artist. Her beauty was constantly shifting with her roles, and because she was a consummate actress she changed radically for every part.”

If there is any finer tribute a director can give an actress, I’d like to hear it.

And here’s to you, Anne Bancroft.