For those younger movie fans who only know veteran actor Albert Finney from his more recent work in movies like “The Bourne Ultimatum” (2007) and “Skyfall” (2012), this piece should take you on a voyage of discovery. In truth, you can be forgiven for not knowing just how accompished he is, because though Finney is extremely dedicated to his craft, he cares very little about publicity.

Nominated five times for an Oscar, he has never attended the ceremony. Offered a knighthood fifteen years ago, he declined to accept, commenting: “Call me Sir if you like! Maybe people in America think being a Sir is a big deal. But I think we should all be misters together. I think the Sir thing slightly perpetuates one of our diseases in England, which is snobbery.” To his credit, even as one of Britain’s most respected actors, he has never forgotten his working class roots in Manchester, where his father was a successful bookie.

A graduate of RADA (the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), the young actor cut his teeth in the fifties performing at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre (later the Royal Shakespeare Company). Finney’s prodigious raw talent was quickly noted, and no less a light than Charles Laughton took the fiery, charismatic young actor under his wing. Fame seemed assured — and was.

The movie public’s first prolonged exposure to the Finney phenomenon took place in Karel Reisz’s gritty “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” (1960). Another top entry in a series of British working-class dramas then in vogue, “Saturday” features Finney as Arthur Seaton, a small-town factory worker whose dreary job makes him live for wild, debauched weekends. He regularly beds his co-worker’s wife, Brenda (Rachel Roberts), but then falls for Doreen (Shirley Ann Field), a proud young woman who demands a commitment Arthur can’t make. Drowning five days of stagnation in one night’s revelry, Arthur is the quintessential angry young man, going nowhere but not letting himself care. Finney is magnetic in the lead, and both Roberts and Field make compelling love interests.

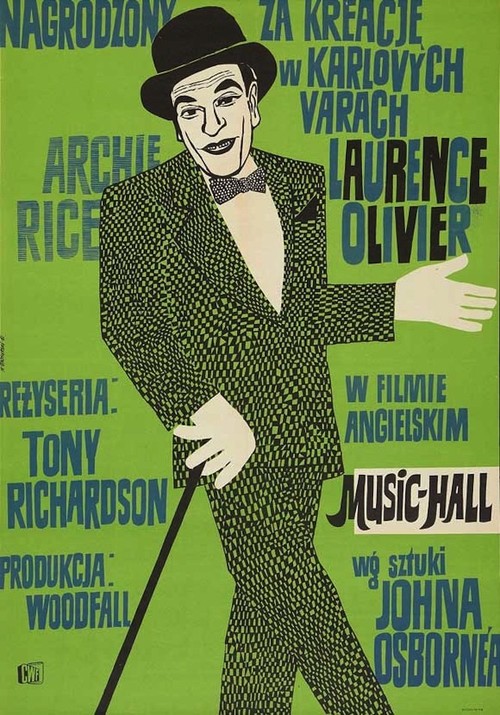

Known for making bold and independent choices, Finney actually turned down the starring role in “Lawrence Of Arabia,” since the role would have involved an extensive time commitment and required him to sign a long-term contract. Instead, he’d cement his stardom in Tony Richardson’s “Tom Jones” (1963), which not only won the best Picture Oscar but also brought him his first of four Best Actor nods. Finney brings enormous gusto to the title character, an orphan adopted by a wealthy squire in eighteenth century Britain. In young adulthood, Tom’s good looks and lusty nature fuel an irresistible attraction to the opposite sex. With various parties set against him due to his humble birth and shaky morals, Tom can’t win the approval of Squire Western (Hugh Griffith) to marry daughter Sophie (Susannah York). Soon Tom leaves home to seek his fortune, and a host of bawdy adventures ensue. “Tom Jones” boasts a fast-paced screenplay by John Osborne, a zippy harpsichord score, and game performances from Griffith, York, Joan Greenwood, Diane Cilento, Edith Evans, and a young David Warner.

In Stanley Donen’s chic, scenic romance “Two For The Road” (1967), the ups and downs of matrimony are deftly explored via vacations past and present in the lives of affluent couple Mark and Joanna Wallace (Finney and Audrey Hepburn). We see the bloom of early romance recede as the two adjust to new life priorities, and struggle to maintain their intimacy and affection. This smart, knowing film showcases Hepburn as the epitome of sixties chic, with Finney an ideal counterpoint as the salty, rugged Mark. Swank European locales and a memorable Henry Mancini score add requisite zing to this mature, nuanced love story. William Daniels and Eleanor Bron are also memorable as another married couple with a child from hell, who unwittingly cause Joanna and Mark to examine their own union.

Next, in Sidney Lumet’s flavorful rendering of Agatha Christie’s “Murder On The Orient Express” (1974), an unrecognizable Finney is transformed into renowned Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot. When a despised financier (Richard Widmark) is murdered on the famous train line, every passenger is a suspect in the eyes of the punctilious Poirot. With the train stalled between Istanbul and Paris, he begins to question the motley group, and gradually uncovers the most unlikely of culprits. Beyond Finney’s astonishing portrayal, the fun of this whodunit comes from the colorful assortment of characters he interrogates, played by the likes of Lauren Bacall, Sean Connery, Wendy Hiller, John Gielgud, and an Oscar-winning Ingrid Bergman (among others). Packed with period charm, “Murder” should be nirvana for any mystery lover.

In the early 80s, the actor would latch on to another juicy character role opposite fellow Brit Tom Courtenay in Peter Yates’s “The Dresser” (1983). Finney plays an aging Shakespearian actor performing “King Lear” with his troupe in the English provinces as German bombs drop during the Blitz. The wartime buffeting of Britain mirrors the physical and mental collapse of this weary thespian, who has performed “Lear” over two hundred times but now can’t remember the opening lines. Courtenay is every bit Finney’s equal as Norman, the actor’s intensely loyal, long-suffering “dresser”, and the only person who can get “Sir” on-stage for each performance. Anchored by two unforgettable lead performances, the gifted Eileen Atkins also resonates as Madge, the company’s spinsterish stage manager whose quiet love for Sir has always competed with Norman’s, and like his, entailed enormous sacrifice.

Next comes the Coen Brothers’s “Miller’s Crossing” (1990), a worthy tribute to the gangster genre perfected by the brothers Warner in the thirties. Leo O’Bannion (Finney) is a crime boss with a big problem: his girlfriend’s brother Bernie (John Turturro) has cheated the head of a rival Italian gang, who wants Bernie dead. Leo lets his love for Verna (Marcia Gay Harden) interfere with his business sense, and resolves to protect Bernie, even if it means starting a war. This decision, along with other complications, puts Leo’s trusted lieutenant Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne) on the outs with his mentor, but Tom steadily works to put things right behind the scenes. Evocative, clever and beautifully played, “Crossing” is an underrated gem, with a nicely mellowing Finney standing out in a game cast.

In 2002, with Albert Finney at retirement age, he would do anything but retire, much like Winston Churchill, the outsize, inexhaustible statesman he so expertly portrays in HBO’s “The Gathering Storm.” Richard Loncraine’s fascinating, atmospheric film focuses on Churchill’s time in the wilderness between the two World Wars, when his warnings of Nazi intentions were dismissed as the rantings of a war-mongering has-been. “Storm” deftly blends the drama of a brilliant but isolated figure whose prescience will usher in a glorious second act, with a tender portrayal of Winston’s almost child-like love for wife Clementine (Vanessa Redgrave). Notwithstanding solid support from Jim Broadbent and Sir Derek Jacobi (as Churchill’s nemesis Stanley Baldwin), “Storm” is elevated by the chemistry between its two stars. With Finney, we witness a truly great actor stepping into the shoes of a truly great man- and the fit is perfect.