‘Tis the season again, when thoughts (and hopefully eyes and ears) turn to that perennial Christmas classic, Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946). Astonishingly, this dark, brilliant film was not an immediate hit with war-weary audiences on release, but over the decades, has become perhaps the most beloved and admired holiday picture of all time.

Before we claim it as Jimmy Stewart’s movie, let’s consider the man who plays the sweet but tragic Uncle Billy, Thomas Mitchell. Though Lionel Barrymore undoubtedly has the showier role as the stingy Mr. Potter, watch Mitchell’s performance closely this time around. It breaks your heart.

Thomas Mitchell was one of the most admired and successful character actors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, but to most viewers today, his face is more familiar than his name. When you hear more about Mitchell’s amazing career, you’ll agree we should all know his name — and revere his memory.

Consider this: in 1939, widely considered the pinnacle year of the studio system, Thomas Mitchell appeared in three of the ten movies nominated for Best Picture (“Gone with the Wind,” “Stagecoach,” and “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington”), as well as two more Oscar-nominated favorites, “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” and “Only Angels Have Wings.”)

Imagine any actor today making five movies in a year, much less five enduring classics.

He was also the first person to achieve the “Triple Crown” of acting, winning an Oscar, an Emmy and a Tony. His Oscar came first for his portrayal of the tippling doctor in John Ford’s “Stagecoach,” the movie that launched John Wayne. In 1952, he won his Emmy for his recurring role in the medical drama, “The Doctor,” and the very next year brought the Tony for his performance in “Hazel Flagg,” a stage adaptation of the 1937 screwball comedy, “Nothing Sacred.”

Thomas Mitchell was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey in 1892, the youngest of seven children. His parents were Irish immigrants. His father James, who’d die when Thomas was still a boy, was a newspaperman, and Thomas’s older brother also became a journalist. This too was where “Tommy” started, working at a series of newspapers. (Trivia note: his brother James Mitchell would eventually serve as Secretary of Labor in the Eisenhower administration.)

But Tommy had a creative bent that drew him more to the theater than the newsroom. It’s a little known fact that in addition to being a superb actor, Mitchell was a director, playwright, and screenwriter. Indeed, one of his early plays, “Little Accident,” was made into a film (three times!) in Hollywood.

Still, acting would become his bread and butter and occupy most of his time. His first big break came from an older man who’d also eventually become a first-rate character actor on the screen: Charles Coburn (best remembered as Barbara Stanwyck’s card-sharp father in Preston Sturges’s “The Lady Eve”). In 1913, Coburn was heading a highly regarded Shakespearian troupe, and hired Mitchell. A period of crucial training followed.

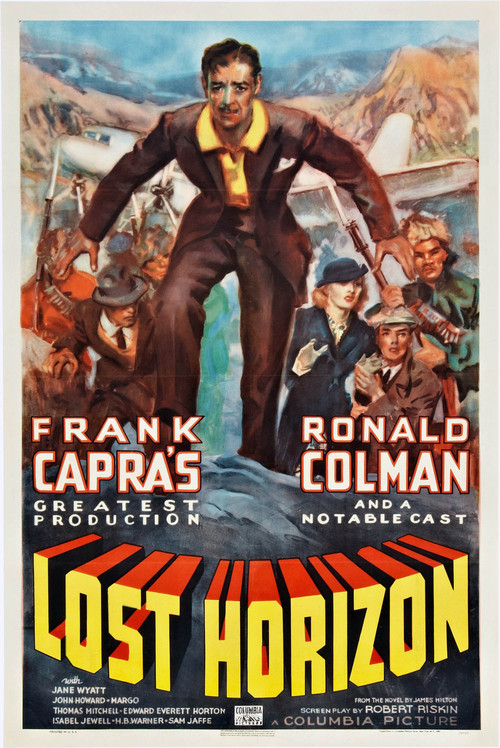

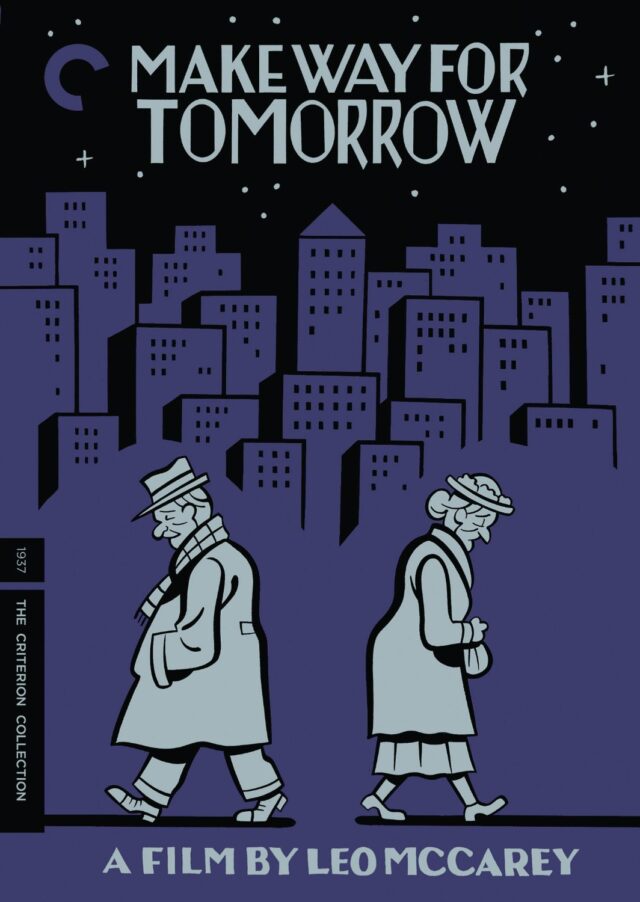

Aside from one silent film role in 1923, Tommy was dedicated to the Broadway stage for the next two decades. Eventually, with Broadway hurt by the ongoing Depression, Mitchell ventured west to Hollywood. He first scored in the underrated screwball “Theodora Goes Wild” (1936), then cemented his career the following year with three films: Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon,” Leo McCarey’s “Make Way For Tomorrow,” and John Ford’s “The Hurricane,” which brought him his first Oscar nod.

And then came 1939, and his most famous role, as Gerald O’Hara in “Gone with the Wind.” Who can forget that moment when he turns to his vain daughter Scarlett and asks: “Do you mean to tell me, Katie Scarlett O’Hara, that Tara, that land doesn’t mean anything to you? Why, land is the only thing in the world worth workin’ for, worth fightin’ for, worth dyin’ for, because it’s the only thing that lasts.”

But it would be the part of Doc Boone in “Stagecoach” that won him his statuette that year. In accepting, Mitchell was characteristically humble, telling his audience: “I didn’t think I was that good. I don’t have a speech — I’m too incoherent.”

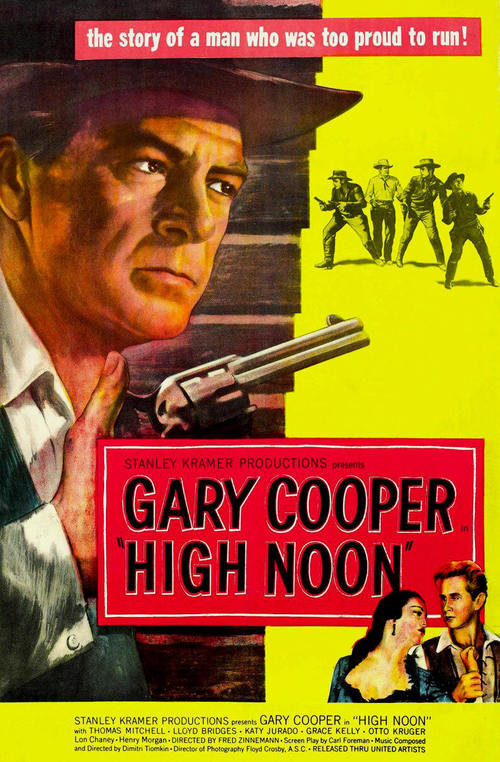

And the roles kept on coming throughout the forties, in familiar titles like “The Long Voyage Home” (1940), “The Black Swan” (1942), and “Bataan” (1943). Beyond his triumph in “Wonderful Life”, he also played the Mayor in 1950’s seminal Western “High Noon.”

Mitchell brought an emotional honesty and vulnerability to every role he played. Perhaps the most heartrending moment in “Wonderful Life” occurs when Uncle Billy first realizes he’s misplaced all the bank deposits. The growing panic that sweeps over his face still hits you in the gut, even after multiple viewings.

Thomas Mitchell had a pretty wonderful life himself. After a short second marriage, Mitchell reunited with his first wife Anne. That union produced one daughter and endured up to his death at 70 from cancer.

He had many friends, and enjoyed his drinks. Little surprise that he counted W.C. Fields, John Barrymore, and Errol Flynn among his closest companions. He was, of course, widely respected- not just for his native abilities, but also his down-to-earth attitude about his chosen profession.

He once said: “A lot of people say I’ve deserted my art because I left Broadway and the stage. Hell, I’m no artist. I’m a working man. I’ve got a trade just like any other mechanic, and I follow my trade where the work is. Just now it’s in Hollywood, but I’m not tied to Hollywood.”

Thomas Mitchell was, in fact, tied to the craft of acting, writing, and directing, wherever it took him. And all these years later, we remain the beneficiaries of his dedication and talent.

Rest well, Tommy.