There is a wonderful video currently making the rounds of social media that captures a luncheon celebrating the 25th anniversary of MGM, “the Tiffany of studios,” in 1949.

The newsreel camera pans across long tables filled with stars, who for the most part look relaxed and content as they chat with their neighbors. At the end of one table, the camera stops and we see the immortal silent star Buster Keaton, by this point relegated to the occasional minor role and developing gags behind the camera.

He seems alone and apart from everyone else. He sees the camera and plays to it, looking as if he’s been caught doing something indecent as he fiddles with a large piece of celery. It is a sublime moment which breaks your heart even as you laugh.

Just a quarter century earlier, Buster Keaton had been one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, who left an indelible mark on silent film comedy, along with his contemporaries Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd.

He was born Joseph Frank Keaton into a vaudeville family in 1895, and it’s claimed his father Joe’s business partner, the magician Harry Houdini, gave the young boy his nickname after seeing him fall down a flight of stairs without being injured.

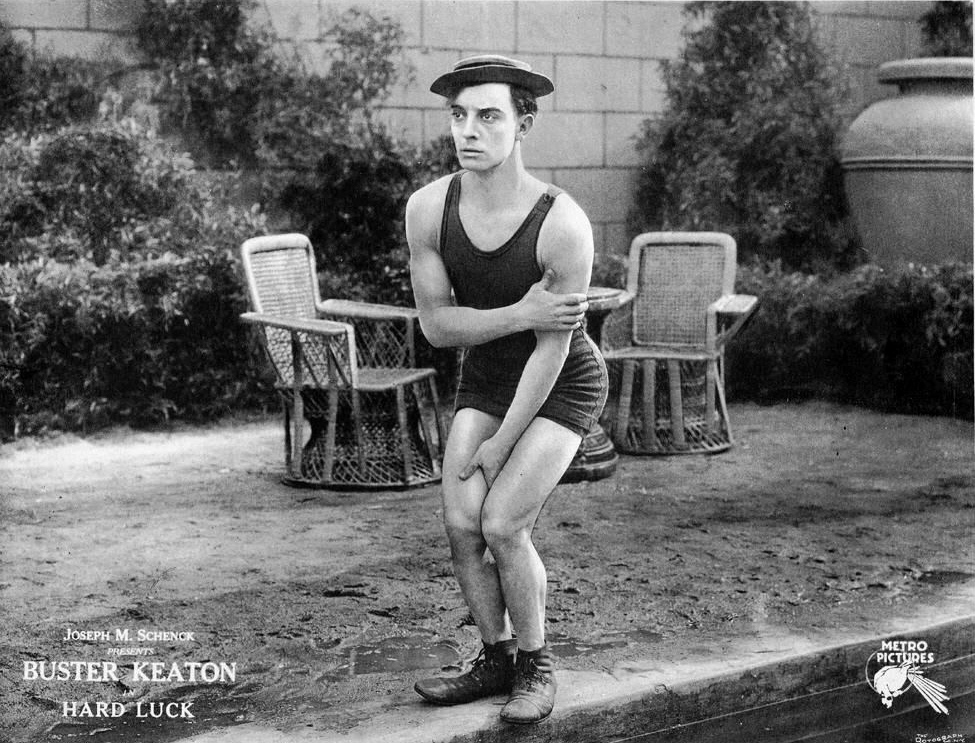

Buster became part of his parents’ act when he was just three, and the routine he did with his father made full use of this tiny boy’s uncanny flexibility. It involved young Buster goading his Dad to the point where the older man would knock the kid around the stage, or even throw him off it. A luggage handle was even sewn into young Buster’s costume to make it easier to toss him. The act was often billed as “The Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged.”

How did the boy survive, then and later? As he explained it: “The secret is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It’s a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I’d have been killed if I hadn’t been able to land like a cat.”

Incredibly, Keaton enjoyed doing these routines, but early on noticed that he got fewer laughs if he was smiling while flying through the air. So he adopted the deadpan expression that would define his comic identity in years to come.

By the time Buster turned 21, his father’s alcoholism had advanced to the point where he could not be relied on to perform. So he and his mother left for New York City, still the Mecca for vaudeville, and also home to the relatively new medium of silent film.

Keaton then went to France to fight in World War 1, and on his return began working on a series of short films with established star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. Before fully committing to the job, however, Buster had gone home with a movie camera, taken it apart, then re-assembled it to understand just how the process worked. Once enlightened, he never looked back.

He and Arbuckle would make fourteen films together through 1920, with Buster serving as co-star, second director and gag man. It was a true collaboration. Both Arbuckle and Keaton were under contract to Joseph Schenck, who’d later head MGM. Schenck decided that on the basis of his work with Arbuckle, Keaton deserved his own unit and the chance to be featured as a solo performer.

Buster’s first full-length film, “The Saphead” (1920), set him on a course to stardom. Over the better part of the decade to come, he’d conceive, direct and star in some of our finest and most enduring silent comedies. He’d also invent and execute all his own stunts over this period.

With each new picture, Keaton became more daring, imaginative and ambitious. He had a carefully considered approach to shooting his films. As he expressed it: “When I’ve got a gag that spreads out, I hate to jump a camera into close-ups. So I do everything in the world I can to hold it in that long-shot and keep the action rolling. Close-ups are too jarring on the screen, and this type of cut can stop an audience from laughing.”

His own character was always the underdog — the small, retiring fellow others at best overlook, or at worst bully. “The Great Stoneface,” as he came to be known, had incredibly expressive eyes, betraying an inner well of sadness, but still there was none of Chaplin’s overt sentimentality or Lloyd’s broad mugging in his work. Keaton underplayed brilliantly, and this is partly why his work holds up so well.

And then of course, there are the stunts, those inspired visual sight gags, some of which we’ve included in this piece. Almost a century after they were shot, they still have to power to amaze. You have to be impressed by Harold Lloyd hanging from the tops of buildings (no special effects, folks), but it’s the sheer ingenuity of Keaton’s often hazardous set pieces that stays with you.

Prime example: in 1928’s “Steamboat Bill, Jr.”, Buster has the frame of a building fall on him, but he just happens to be standing where the empty door frame is situated. This in fact was an extremely risky maneuver, requiring exacting precision. If he’d been off his mark by even one eighth of an inch, he’d have been crushed.

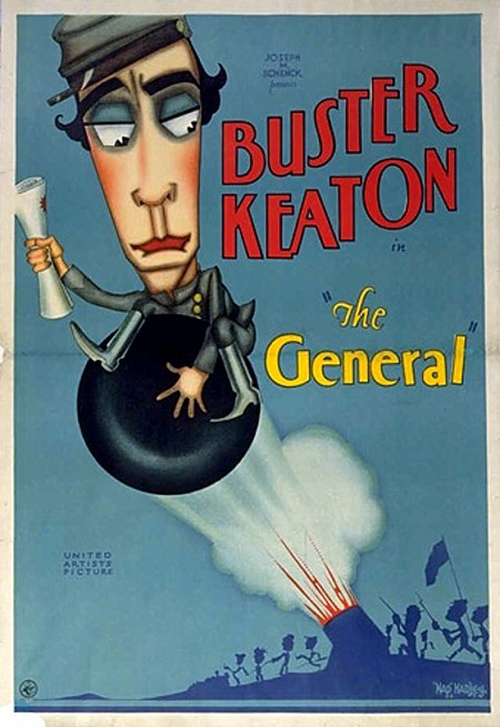

Most critics and historians view “The General” (1926) as his masterpiece. The film was based on a real event during the Civil War, when a group of Union soldiers and renegades stole a Confederate train and headed north, cutting supply lines along the way. No less a light than Orson Welles referred to it as “the greatest comedy ever made, the greatest Civil War film ever made, and perhaps the greatest film ever made.”

But it was expensive, and not an immediate success on release. Thus started a gradual process whereby Keaton would lose the creative control that allowed him to thrive. In 1928, MGM picked up his contract, but started insisting that he use stunt doubles and that others direct him.

As sound pictures came in, Buster felt he was in a straitjacket. The alcoholism that had destroyed his father began afflicting him. By 1930, he no longer seemed to care about much of anything, and MGM fired him. His hey-day in films had lasted a little over a decade.

Several very bad years followed, with first wife Natalie Talmadge divorcing Keaton in 1932, and cleaning him out with a hefty settlement. By the end of the thirties, however, Keaton had conquered his drinking problem and met actress Eleanor Norris, a much younger woman who’d keep him happy- and sober- for the rest of his life.

In the quarter century that followed, Buster worked in Hollywood as a gag man, did some “B” two-reel comedies, and made the occasional fleeting appearance in prestige pictures, like “Sunset Boulevard” (1950), Chaplin’s “Limelight” (1952), “Around The World in Eighty Days” (1956) and “It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad World” (1963). He also found work in television, appearing in single episodes of “The Twilight Zone,” “Route 66,” and “The Donna Reed Show.”

Reaching the age of sixty, Buster began to receive the attention and admiration that had deserted him over two decades before. His TV work re-ignited interest in his silent films. In 1957, a biopic called “The Buster Keaton Story” was released, starring Donald O’Connor, and Keaton was celebrated on the popular TV program, “This Is Your Life.”

A few years later, he landed a recurring role in American International Studio’s string of “beach party” comedies, starring Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello. On the set of these pictures, Keaton particularly enjoyed getting to know rising comedians Don Rickles and Buddy Hackett, who clearly revered him.

Buster Keaton’s final film was 1966’s “A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum.” Shortly after production wrapped, Buster, a longtime smoker, developed a hacking cough which turned out to be advanced lung cancer. Knowing he had little time left, Eleanor chose to tell him that he had a bad case of bronchitis. In motion till the end, Keaton paced his hospital room, and was reportedly up and about until the day before he died, on February 1, 1966.

Asked about his topsy-turvy life, he once said with characteristic humility: “I’ve had few dull moments and not too many sad and defeated ones…I am by no means overlooking the rough and rocky years I’ve lived through. But I was not brought up thinking life would be easy… And the bad years were so few that only a dyed-in-the-wool grouch who enjoys feeling sorry for himself would complain.”

On another occasion, a friend asked him about what satisfied him most. He replied: “I like to be with a happy crowd.”

Thanks for making us all happy, Buster.

More: 12 of the Best Classic Movies Streaming on Amazon Prime