Tyrone Power: If ever a name sounded like the product of a studio publicity department, this was it. Yet this dark, impossibly handsome star (known to friends as “Ty”) used his own name, the same one carried by his actor father and his great-grandfather, also a famed actor in nineteenth-century Ireland.

The senior Tyrone Power had emigrated from Britain in the 1880s, and having briefly tried his hand at farming, decided to go into the family business. He became a successful touring actor, finally starting a family at the age of 45, with the birth of his only son in 1914.

With his father away most of the time, Ty and his younger sister Ann were raised by their mother in Cincinnati. In 1920, the parents divorced. After high school, Ty decided to pursue acting over college, and joined his estranged Dad in Los Angeles to learn the trade.

By then, Tyrone, Sr. had sustained a solid career, not only on the stage but in silent films. He had just finished his first talkie, ”The Big Trail” (1930), opposite a promising newcomer named John Wayne. His next project would be “The Miracle Man,” a remake of a Lon Chaney picture.

The father/son apprenticeship Ty had hoped for was cut short when, in December 1931, his father suffered a massive heart attack during production. He died in his son’s arms. Ty managed to win a small part in a film shortly after his father’s death, but no other offers were forthcoming, and he decided to go back east to pursue stage work.

Several years later, director Henry King spotted him, and thought him a natural for the screen. He proposed Power for the lead in the upcoming Fox production of “Lloyds of London” (1936), a role that had been slated for Don Ameche. Reluctantly, studio head Darryl Zanuck decided to roll the dice on Power. He would be very glad he did, and Henry King was also happy: he and Power would make ten more movies together.

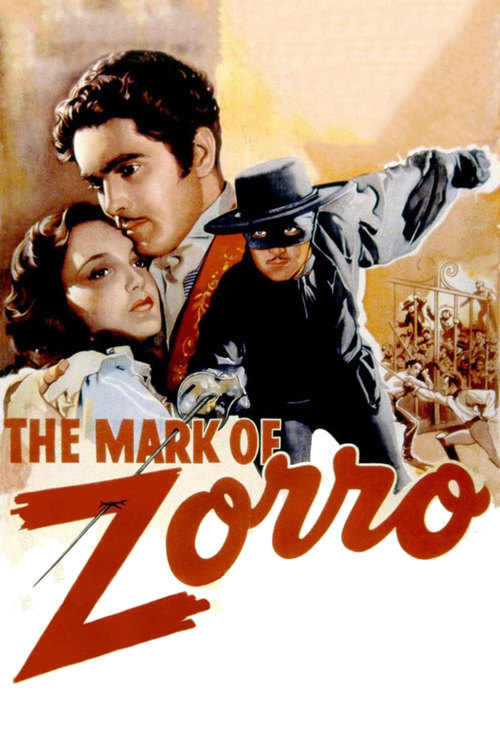

Much like his contemporary Errol Flynn, Power became a romantic star overnight. Also like Flynn, his natural grace and athleticism made him a natural for swashbuckling roles. According to actor and expert fencer Basil Rathbone, who would go up against both stars on-screen, Power was by far the more skilled swordsman. (In particular, 1940’s “The Mark of Zorro” is an excellent showcase for his impressive fencing skills).

Ty had taken up flying in the late ‘30s and when the Second World War broke out, he wanted to get into the air as soon as possible to support the effort. Based on his prior training, he was able to take an accelerated course and earn his wings in the Marine Corps. He ended up flying cargo planes into combat areas, including Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He’d win several medals for heroic service and remain in the Marine Corps reserves after the war, attaining the rank of Major.

The war and a string of infidelities (including Lana Turner) had taken its toll on his first marriage to French actress Annabella. They would finally divorce in 1948. Power would then marry another actress, the gorgeous Linda Christian, who would give him two daughters.

Power had come back from overseas with a firm intention to stretch himself as an actor and broaden his appeal. As he put it: “I’m sick of all these knights in shining armor parts, I want to do something worthwhile like plays and films that have something to say.” He had to fight Zanuck hard to get these types of roles, as the chief did not want to mess with a winning formula. But he also wanted to keep Ty happy and in the fold.

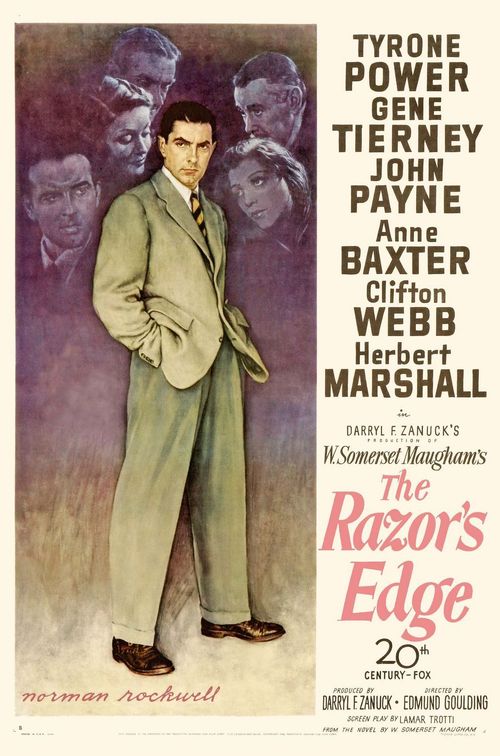

The two films that best succeeded in challenging Power’s pretty boy image were “The Razor’s Edge” (1946) and most notably, “Nightmare Alley” (1947), a brilliant, offbeat noir directed by Edmund Goulding. Zanuck chose not to promote the film, and so it died a quick death at the box office. Still, the critics recognized how good it was, and how good Power was in it. It would become the movie Ty was proudest of making.

In between these gems came more of the same formulaic outings that had worked so well for Fox in the past. But Ty was using his clout now, turning down more parts and demanding profit participation for more commercial projects he’d otherwise not take. He was also pursuing more stage work, including, in 1950, an extended run of “Mister Roberts” in London’s West End. Increasingly, he would return to the theatre from this point on.

After his second divorce from Linda Christian in 1955, he entered into a long-term relationship with Swedish actress Mai Zetterling, but twice burned, shied away from marriage. That changed when he met Debbie Minardos in 1957, a radiant lady nearly a quarter century his junior. The couple would marry in 1958, and she would quickly become pregnant with Ty’s third child.

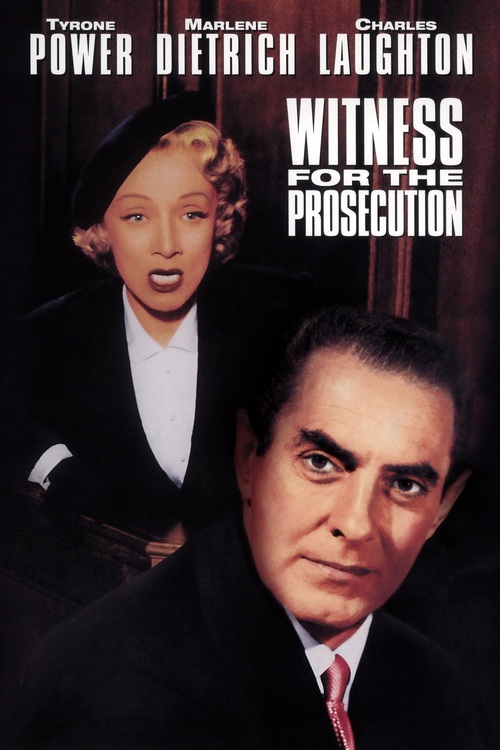

Power would never meet his son and namesake. Having completed the Billy Wilder thriller “Witness for the Prosecution” (1957), the actor traveled to Madrid to shoot the historical epic “Solomon and Sheba.” After filming a taxing duel scene with good friend and co-star George Sanders, he collapsed on the set. Like his father before him, Ty would succumb to a massive heart attack in the middle of a film production. Yul Brynner was called in to replace him.

But while his father lived into his 60s, the younger Power never made it to 45. (Certainly a three pack a day cigarette habit didn’t help.) Factoring in his military service, his career had spanned less than two decades, yet he still made Quigley’s list of the top hundred box office stars. This attests to his immense popularity, since most of the other names had much longer runs.

But Tyrone Power cared less about being a great star than a great actor. In the end, he succeeded admirably on both counts.