In the 1930s, when so many women in America were still relegated to the kitchen and nursery, one actress in Hollywood became a star playing independent women who worked for a living, competing with men in a man’s world. Her name was Jean Arthur.

Just 5’3”, and endowed with a uniquely husky, smoky voice, Jean never could bring off the role of pliant wife or decorative beauty. There was a hard-earned wisdom, a certain admirable stubbornness about her. Here was a lady who’d lived.

Even with this dark, complex undercurrent in her character, through sheer talent, charisma and hard work she became one of the finest screen comediennes of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

It was a long, bumpy road to stardom. Born Gladys Greene in upstate New York in 1900, she was an afterthought, with two much older brothers. Her innate shyness and a peripatetic childhood made it particularly difficult for her to make enduring friendships. She would remain a somewhat solitary and extremely private person for the rest of her life.

She wanted to act, she said, simply so she could become someone other than herself. The Fox Film studio had spotted her while she was working as a commercial model in the early twenties. Signed to a short-term contract, she debuted in John Ford’s “Cameo Kirby” (1923). Somewhere around this time she changed her name to Jean Arthur, reportedly paying tribute to both Joan of Arc and King Arthur.

Her lack of experience and discomfort in front of the camera almost derailed her career at the outset. Having been fired from her second picture, she toiled in comedy shorts. She was then hired for a series of “B” westerns on location in the steaming California desert, a grueling experience.

Jean then scored modestly in a few more ingénue roles, enough to win a contract with Paramount in 1928. There she became briefly involved with an up-and-coming executive named David O. Selznick. Shortly after he left the studio in 1930, she was released from her contract.

Jean was just 30, and after seven tough years, she had failed in Hollywood. Many in her place would have quit for good, but she sensed she could improve her technique with the proper training. So she moved back East, and set her sights on Broadway.

Happily, she finally blossomed there. Though she had few actual hits, she gained confidence and the critics were praising her. As she herself remembered this pivotal period: “On the stage…the individual counted. The director encouraged me and I learned how to be myself. I learned to face audiences and to forget them. To see the footlights and not to see them; to gauge the reactions of hundreds of people, and yet to throw myself so completely into a role that I was oblivious to their reaction.”

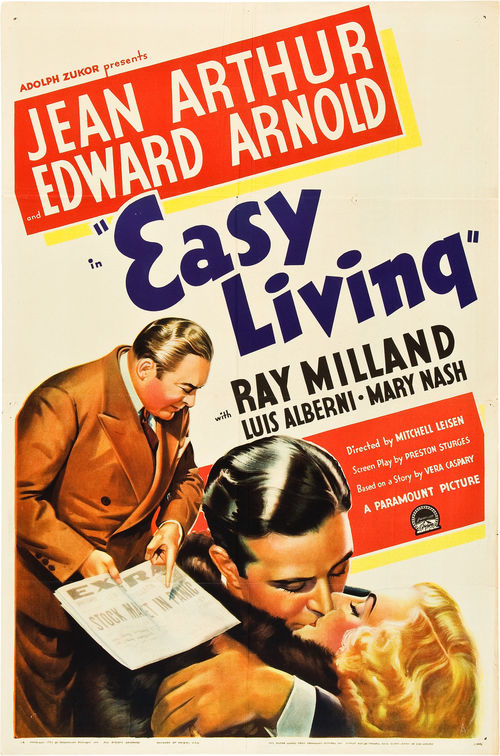

Several years later, she returned to Hollywood a seasoned, self-assured actrress. Now working in sound pictures, she could use her distinctive voice to her advantage. Her breakthrough came in John Ford’s comedy “The Whole Town’s Talking” (1935), opposite Edward G. Robinson. By this time, she had already caught the eye of director Frank Capra, who cast her in his next picture, “Mr. Deeds Goes to Town,” starring Gary Cooper.

This comedy classic would establish Jean’s image as a tough, savvy professional woman whose cynical exterior masks a big heart underneath. Her character, Babe Bennett, is an ace reporter who pretends to romance Cooper’s Longfellow Deeds, a hayseed who has just inherited millions from a distant cousin. Though her goal is to win a big scoop on Mr. Deeds for her paper, eventually she tires of the ruse as she develops feelings for her subject.

Jean’s chronic stage fright was painfully evident at this point- that is, until the cameras rolled. She would flee to her dressing room between takes to throw up. Cooper, whom she’d later cite as her favorite co-star, had a laid-back, mellow style on-screen and off, and was one of the few actors she worked with who could relax her.

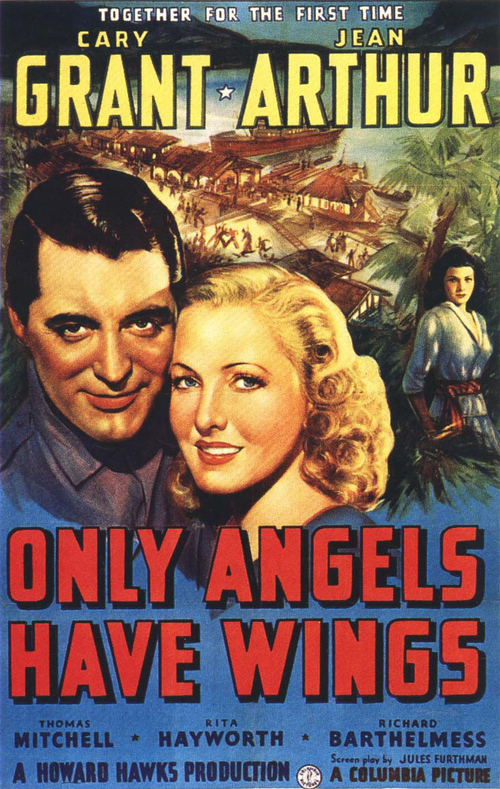

“Deeds” made Jean Arthur a star, and over the following eight years, she’d go on to make a series of classic films, working with the top actors and directors in the industry. Notably, she’d make two more films with Capra (1938’s “You Can’t Take It with You”, which won the Best Picture Oscar, and the following year, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington”) and two with George Stevens (1942’s “The Talk of the Town,” and 1943’s “The More The Merrier,” which netted her a Best Actress Oscar nod).

Even with success, Jean was at best ambivalent about her chosen calling. She once said she’d prefer to have her throat slit to doing an interview. She hated the exploitation, ruthlessness and cruelty inherent in the movie business. And due to her nerves, every role in every film was emotionally taxing for her.

Thus, at the height of her fame in 1944, Jean walked away from her contract with Columbia Pictures. It’s claimed that when her release came through, she actually ran through the backlot, screaming “I’m free! I’m free!”

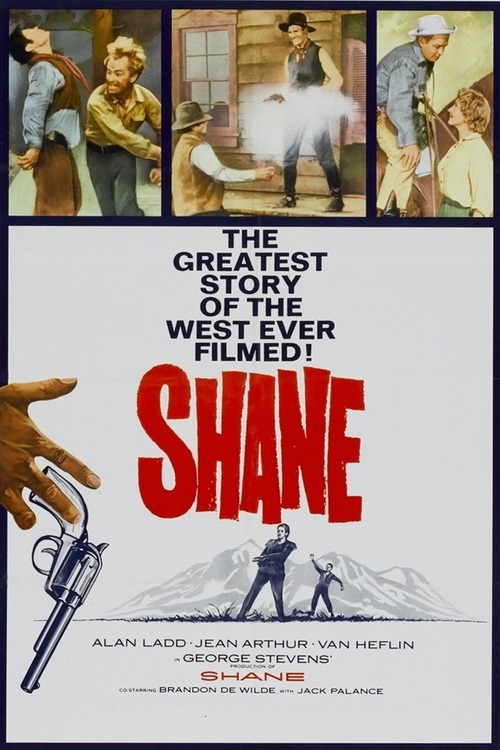

Jean did not retire permanently. She did two more acclaimed films over the following decade: Billy Wilder’s “A Foreign Affair” (1948), and George Stevens’s “Shane” (1953). She also scored as Peter Pan on Broadway in 1950. Yet her growing unease with crowds and public life would prevent her from achieving any further sustained success, either on stage or screen.

With astonishing candor and self-awareness, she’d once described her temperament in these words: “I am not an adult, that’s my explanation of myself. Except when I am working on a set, I have all the inhibitions and shyness of the bashful, backward child . . . unless I have something very much in common with a person, I am lost. I am swallowed up in my own silence.”

Jean had no children with husband Frank Ross, an actor/producer whom she divorced after 16 years of marriage in 1949. She had a failed TV show in the mid-sixties, and ended up teaching acting at Vassar, where she spotted a promising young performer named Meryl Streep and predicted stardom for her. Finally, she retired to a quiet life alone in California, an existence she’d craved and fully earned.

Jean Arthur passed away at the age of 90 on June 19, 1991. The critic Charles Champlin eloquently described her lasting impact as follows: “To at least one teenager in a small town, Jean Arthur suggested that the ideal woman could be – ought to be – judged by her spirit as well as her beauty. The notion of the woman as a friend and confidante, as well as someone you courted and were nuts about, someone whose true beauty was internal rather than external, became a full-blown possibility as we watched Jean Arthur.”