It was LA cartoonist Bob Thaves who wrote the following caption: “Sure he (Fred Astaire) was great, but don’t forget Ginger Rogers did everything he did…backwards and in high heels.”

This amusing observation is also perceptive, for what set Ginger Rogers apart, beyond her radiant, athletic, All-American look, was her unbending determination to succeed in an industry dominated by men.

Not surprisingly, Astaire was a perfectionist. He once confided that most of his other female partners would, at some point or other, break down crying at the difficulty of a routine. But, he quickly added, not Ginger. Never Ginger.

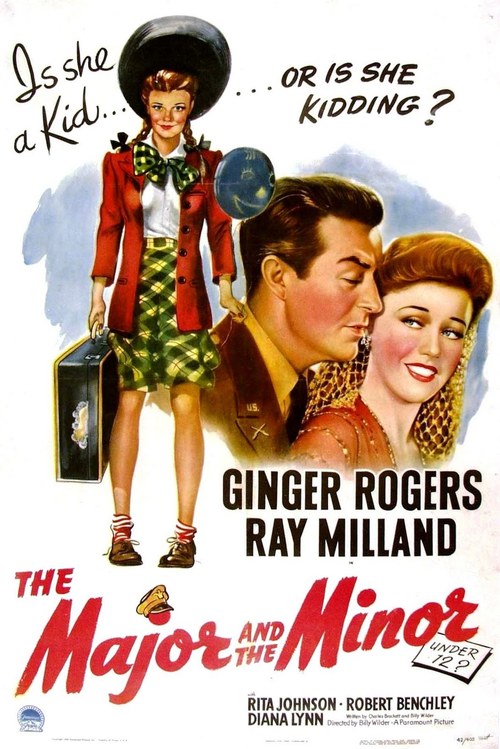

Rogers was as shrewd as she was tough. By the time musicals fell out of favor at the end of the thirties, she had already seen the future and established herself as a first-rate actress and comedienne. She did not need Fred to shine on her own. And no hoofing required.

Thankfully, Fred felt the same way about Ginger. Their mutual desire for independence after a slew of pictures caused speculation that the two did not get along. While they were never close friends off-screen, they were more than cordial and maintained enormous respect for each other.

A teetotaler, Christian Scientist, and staunch Republican who later decried sex and violence in movies, Rogers would never have thought of herself as a feminist. But her life story suggests otherwise.

Born Virginia McMath in Independence, Missouri, she was the only child of Lela Owens Rogers, a formidable, driven mother who was her closest confidante and played a major role in managing her career. (Having divorced Ginger’s father early on, Lela re-married John Rogers, and Ginger took his name).

A natural song-and-dance performer, she started in vaudeville at age 15. A little over three years later, she was cast in “Girl Crazy,” a hit Gershwin musical on Broadway, where she first met Astaire and introduced the hit tune, “Embraceable You.”

When she was finally paired with Fred on film in “Flying Down to Rio” (1933), she’d already scored in “42nd Street,” where she first sang the immortal Depression anthem, “We’re In The Money.” She’d already appeared in over twenty films; he’d only done one. Tellingly, this was the only Astaire-Rogers film where she got higher billing than Fred.

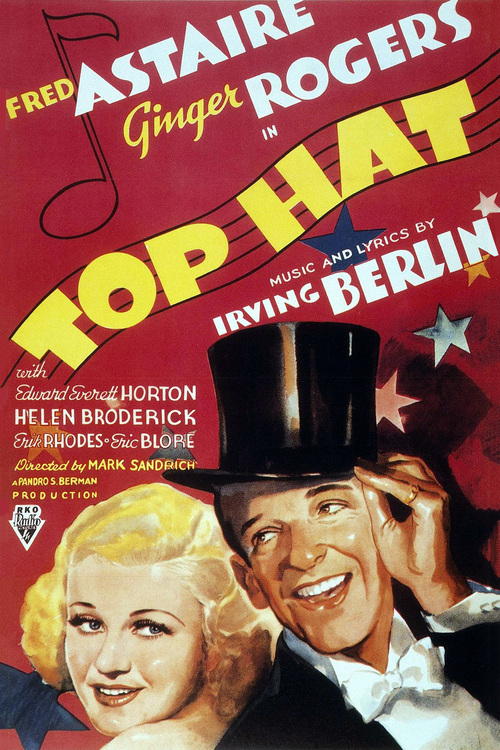

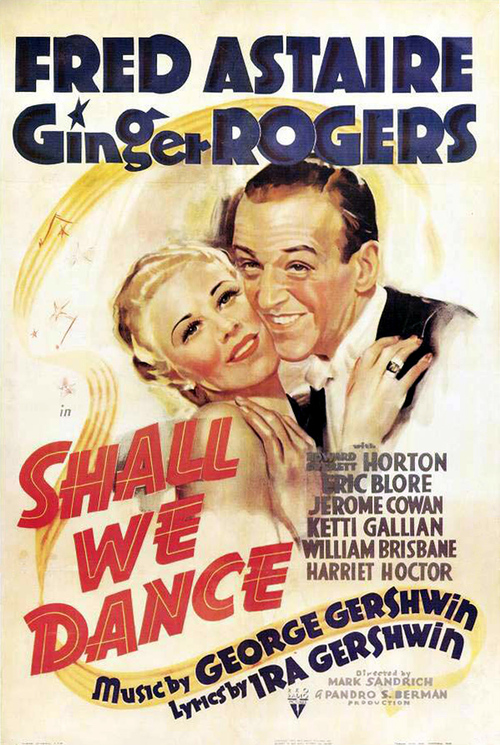

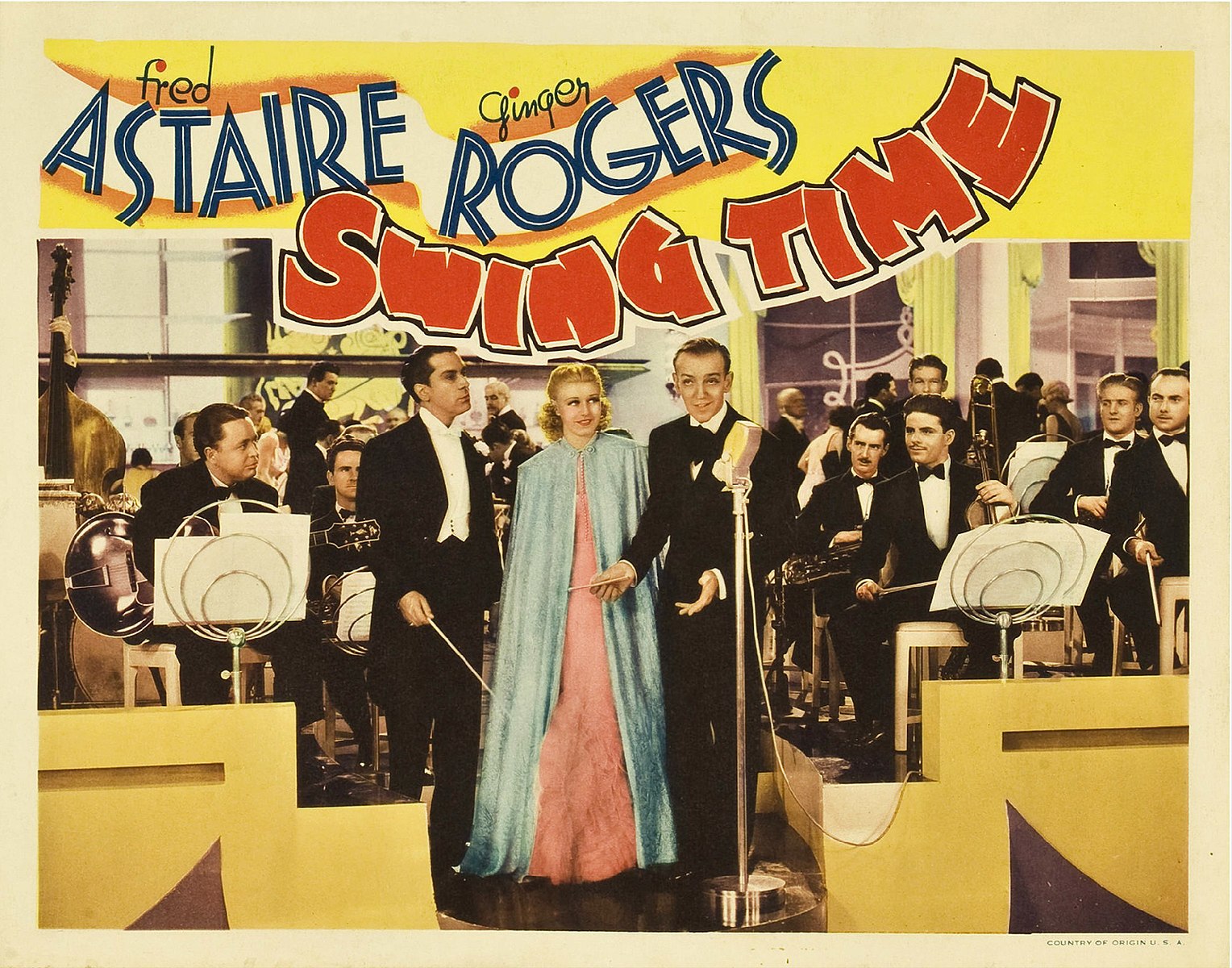

She would go on to co-star in nine movies with him over six years, as RKO milked a winning formula with titles like “Top Hat” (1935) and “Swing Time” (1936). Finally free and flying solo, Rogers triumphed, winning the Best Actress Oscar for the drama “Kitty Foyle” (1940).

She then sustained her solo film career throughout the decade and into the next, becoming one of the most highly paid actresses in Hollywood. Among the films she reportedly passed on were “His Girl Friday”(1940), “Ball of Fire” (1941), and “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946).

Like many female stars of the day, she found good movie roles harder to come by as she approached middle age. Throughout the fifties, she stayed busy, but none of her movies over this period matched her previous work.

Then, in 1965, she made a splashy comeback on Broadway, replacing Carol Channing in “Hello Dolly.” That same year, she also appeared as the Queen in the TV version of “Cinderella,” and in “Harlow,” playing Jean Harlow’s mother. (She must have related to the role of a strong stage mother devoted to Christian Science!)

Four years later, Ginger scored on London’s West End in an acclaimed production of “Mame.” After that, she did the occasional guest TV spot, and fulfilling a long-time wish, also directed an Off-Broadway production of “Babes in Arms” in 1985.

Unbeknownst to many, Rogers was a diabetic, but her belief in Christian Science meant that her last husband, William Marshall, had to trick her into taking insulin shots, saying they were vitamin injections. In April, 1995, she finally lapsed into a diabetic coma, then suffered a fatal stroke. She was 83.

Married (and divorced) five times, including a six-year union to actor Lew Ayres in the thirties, Ginger Rogers devoted her life to becoming and remaining a star. As her career progressed, she fought hard for equal treatment and pay, and worked tirelessly to develop her craft and extend her range.

In the end, she proved to the world that she was much more than Fred Astaire’s dance partner, though that might have been enough for most people.

Late in life, Astaire was asked who his favorite dance partner was. He replied: “Excuse me, I must say Ginger was certainly the one…you know, the most effective partner I ever had. Everyone knows. That was a whole other thing, what we did…I just want to pay a tribute to Ginger because we did so many pictures together and believe me it was a value to have that girl…she had it. She was just great!”

Amen to that, brother.