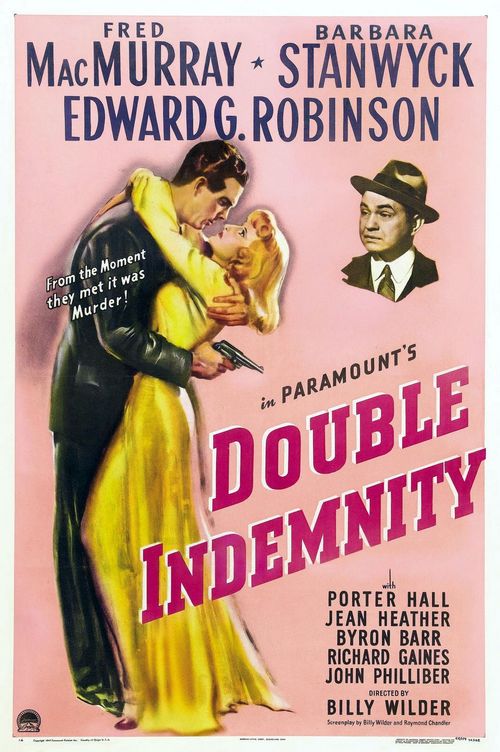

The 1930’s saw the full flowering of hard-boiled detective fiction, with three authors heading the list of purveyors: Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James M. Cain. It’s worth noting that two of these three men would have a hand in creating “Double Indemnity,” one of the first and greatest examples of a subgenre we now refer to as “film noir.”

Cain wrote the original story, which was first released as a series in Liberty Magazine in 1936. The premise was pitch black: an evil femme fatale seduces an insurance man into writing a policy on her husband and then helping her kill him.

The success of Cain’s book ensured that Hollywood would come sniffing around for the movie rights. Soon they were all competing for the story. Then a blunt warning from the head of the new production code persuaded them that the theme was too sordid. All offers were quickly withdrawn.

Eight years later, a Paramount executive saw a reissue of the novella and thought it would be perfect for up-and-coming writer/director Billy Wilder, who wanted to make his first thriller. The studio bought the rights for $15,000, considerably less than the bids from 1936. But this time, no one was backing down: the movie would get made.

Charles Brackett, Wilder’s writing partner, bowed out of the project, finding the premise too distasteful. Wilder always worked best with a partner, so he went straight to the source: Cain himself, who was unavailable.

Next he asked Raymond Chandler, perhaps Cain’s biggest rival. Chandler accepted what would be his first screenplay assignment, ironic in that he’d always had a low opinion of Cain’s talent.

Wilder and Chandler did not hit it off, to put it mildly. Though Chandler was big name in the book world, he knew very little about writing screenplays and the ways of Hollywood in general. Wilder had to teach him, which the proud Chandler resented.

Also, the author was markedly different in person from the characters he wrote about: slightly aloof, formal, prickly, even priggish. He was also severely alcoholic.

A Polish refugee with a string of screenplay credits and two directorial assignments behind him, Wilder was, by contrast, a kinetic bundle of energy, a confirmed womanizer, and way too informal for Chandler’s tastes. He even wore a hat indoors.

These two huge egos eventually combusted, and Chandler quit the film. Wilder had to apologize and beg him to return, a rare display of deference from a director to a writer. But this was Raymond Chandler, after all.

The truth was that Wilder had secretly developed a grudging respect for the man. Early on, the director had pushed hard to have more of Cain’s original dialogue in the film. Chandler insisted the words would not resonate when spoken. Finally, Wilder called his bluff and brought in two actors to recite the dialogue. Much to his astonishment, he soon realized that Chandler was right.

The two men successfully changed elements of the original story to make the film more effective dramatically and also palatable to the production board, most notably beefing up the role of insurance investigator Barton Keyes to be both Neff’s friend and pursuer, and ensuring that both lead characters paid for their crime in the end.

Wilder always had Barbara Stanwyck in mind for the fiendish Phyllis Dietrichson, but when approached, the star was skittish about portraying such a loathsome, low individual. Wilder looked straight at her and asked, “Are you a mouse or an actress?” Chastened, Stanwyck promptly signed on.

Casting the role of insurance man and prize chump Walter Neff proved more challenging, as practically every A-list actor in Hollywood turned it down, including Spencer Tracy, James Cagney, and Fredric March.

Wilder finally approached leading man Fred MacMurray, who had worked with Stanwyck before (on 1940’s “Remember the Night”) and was coasting along nicely playing good guy romantic leads. Neff would be a major departure for him, perhaps even a career risk, but Wilder leaned on him hard to take it. He would never regret his decision, citing Wilder as the director responsible for broadening his range and actually forcing him to act.

Edward G. Robinson, a big star of the prior decade, had just turned fifty, and sensed his career was entering a new stage, with more supporting character roles ahead. To play Barton Keyes, he would have to take third billing. However, as a sweetener, he was paid the same salary as Stanwyck and MacMurray, with fewer lines to learn.

Wilder made one bad decision at the outset, insisting that Stanwyck wear a garish light blonde wig to make her character look more trashy. She hated it, and told him so. Even the studio brass was bewildered, with one suit famously quipping: “We signed Barbara Stanwyck, and here we get George Washington!”

By the time the director realized his mistake, it was too late. Too much footage had been shot, so the wig would have to remain firmly on Stanwyck’s head.

Other minor gaffes: in one scene, MacMurray’s wedding ring is visible, and most egregiously, the door to Neff’s apartment opens out, not in, facilitating a key moment of suspense, but also running counter to the building code of Los Angeles and most every other city, then and now.

It hardly mattered. Released in July, 1944, “Double Indemnity” was a commercial and critical hit, nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture, Director, Actress and Screenplay. However, on Oscar night, it came away empty-handed.

Sometimes, as we all know, Oscar gets it wrong. This was one of those times. The big winner that year was Leo McCarey’s sentimental “Going My Way,” starring Bing Crosby as a crooning, kindhearted priest.

Still a charming though dated film, it cannot hold a candle to Wilder’s dark masterpiece. (Reportedly, Billy was so annoyed as the ceremony progressed that he put out his foot and tripped McCarey as he walked to the stage to accept his award).

Still, Wilder would be vindicated the following year when his next film, “The Lost Weekend,” won Best Picture, Director and Screenplay. “Weekend” would bring the first two of six Oscar wins over his illustrious career.

Meanwhile, “Double Indemnity” remains an extremely influential film, with its crackling dialogue and shadowy black and white cinematography setting the stage for all the outstanding “film noir” entries to come.

Beyond all that, it’s just as fun and entertaining to watch as it was eight decades ago. To paraphrase the doomed Walter Neff: “We’re crazy about you, baby.”

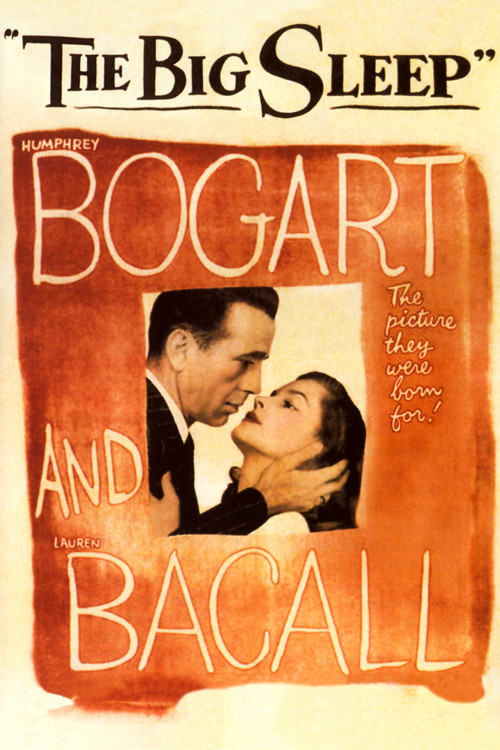

More: Behind the Scenes with Bogie and Bacall in “The Big Sleep”