Many readers will recognize the name of Illeana Douglas, the quirkily appealing actress who appeared in films like “To Die For” (1995) and “Ghost World” (2001), and more recently, popular TV series like “Law and Order,” “Entourage,” and “Modern Family.”

Yet how many recall Melvyn Douglas, the grandfather she so loved and admired?

Personally, I rate him as one of the finest stage and screen actors of the twentieth century. Not only was he awarded two Oscars over his career, but he is one of just nine individuals to attain the fabled Triple Crown of acting, winning an Oscar, an Emmy and a Tony.

He was born Melvyn Hesselberg in 1901, the son of a concert pianist and music teacher who immigrated from Eastern Europe and a Protestant mother whose roots in America extended back to the Mayflower. (He had one younger brother, George, who also became an actor). As a child, Melvyn’s Jewish heritage on his father’s side was never mentioned; he only learned about it as a teenager.

Though his mother wanted a law career for his son, Melvyn knew he wanted to act and left high school to pursue his dream, joining a touring stock company and performing in a range of plays, including the works of Shakespeare.

At this point, Melvyn changed his last name to Douglas, the surname of his maternal grandmother. In 1917, he fabricated his age to serve in World War One, then returned to the footlights.

Douglas made his Broadway debut at 27 portraying a smooth gangster in “A Free Soul.” (Notably, Clark Gable would make his name three years later playing the same role in the film adaptation).

In 1930, he scored again with “Tonight or Never,” which ran for over 200 performances and introduced him to Helen Gahagan, the woman who would share his life. Having ended a brief first marriage in 1927, he was free to wed Gahagan the following year.

With the phenomenon of “talking pictures” in full flower, Hollywood soon came calling. Over the next two decades, Douglas made nearly fifty movies, usually playing a debonair lead or second lead.

Among his many roles, he appeared in James Whale’s atmospheric “The Old Dark House” (1932), charmed Irene Dunne in the delightful screwball farce, “Theodora Goes Wild” (1936), and played opposite megastar Greta Garbo in three films, most memorably the classic Ernst Lubitsch comedy, “Ninotchka” (1939).

He returned to form after serving in World War 2, ably serving as the “other man” to Cary Grant and Myrna Loy in “Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House” (1948). Soon after, the Communist witch hunt in Hollywood began, and Douglas found himself under scrutiny.

He and Helen had traveled to Europe shortly after their marriage, and been shocked by the rampant anti-Semitism there. They swiftly became politically active, outspoken anti-Fascists, and left-wing supporters of President Roosevelt. In 1945, just months before FDR’s death, Helen ran and was elected to the House of Representatives.

In 1950, she ran for a California Senate against a red-baiting congressman named Richard Nixon. He dubbed her “the Pink Lady” for her ultra-liberal views, and she bested him by bestowing the moniker that would stick for the rest of his ill-fated career: Tricky Dick.

Still, for a variety of reasons, he managed to defeat Douglas in an exceedingly ugly campaign. (Though her political career was over, Gahagan Douglas would remain a liberal activist for the rest of her life).

As a result of his own liberal views, Melvyn was gray-listed in 1951, which meant that his film career, if not over, would go on an extended hiatus. Secretly, the Douglas’s were almost relieved. Neither had truly enjoyed their time in Hollywood, and were happy for a change, both in venue and, in Melvyn’s case, career focus. Aside from Helen, Melvyn Douglas’s true love was always the stage.

About his early film roles, he said tellingly: “The Hollywood roles I did were boring. I was soon fed up with them. It’s true they gave me a worldwide reputation I could trade on, but they also typed me as a one-dimensional, non-serious actor.”

That issue would get addressed over time.

The family moved their base to New York, where over the next decade, Melvyn kept busy in plays and on television. In 1955, he took over for Paul Muni as trial lawyer Clarence Darrow in the hit play “Inherit the Wind,” and turned in an electric performance. It was a sign of things to come.

New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson commented: “Mr. Douglas is at the peak of his form. For years he has been giving pleasant, facile performances in superficial parts. It is always exciting to see an accomplished actor suddenly take on stature.”

In 1960, Douglas had another Broadway triumph portraying a presidential candidate in Gore Vidal’s “The Best Man.” He won a Tony Award for his performance.

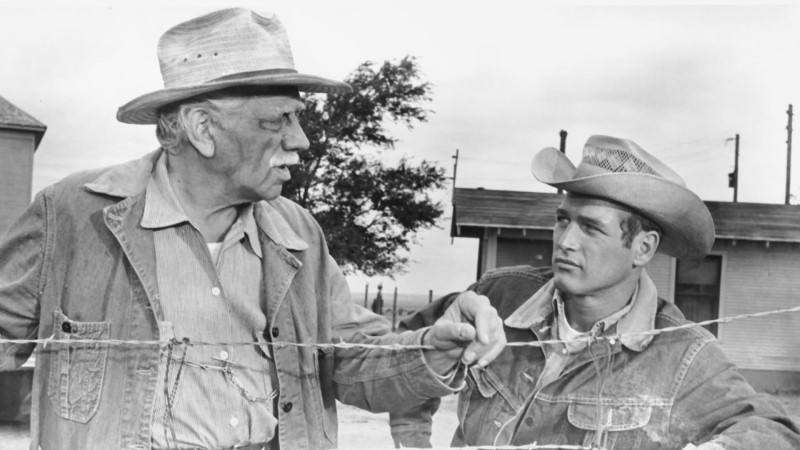

Two years later, with the blacklist dissolved, Douglas was back on the big screen in “Billy Budd,” directed by (and co-starring) Peter Ustinov. Then in 1963 came what many consider the finest role, that of stern, aging rancher Homer Bannon in “Hud.” He’d receive his first Supporting Actor Oscar for this, with co-star Patricia Neal also winning for Best Actress. (Paul Newman, who portrayed his rebellious son Hud, was also nominated).

About his performance, New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote: “Melvyn Douglas is magnificent as the aging cattleman who finds his own son an abomination and disgrace to his country and home. It is Mr. Douglas’s performance in the great key scene of the film, a scene in which his entire herd of cattle is deliberately and dutifully destroyed at the order of government agents because it is infected with foot-and-mouth disease, that helps fill the screen with an emotion that I’ve seldom felt from any film.”

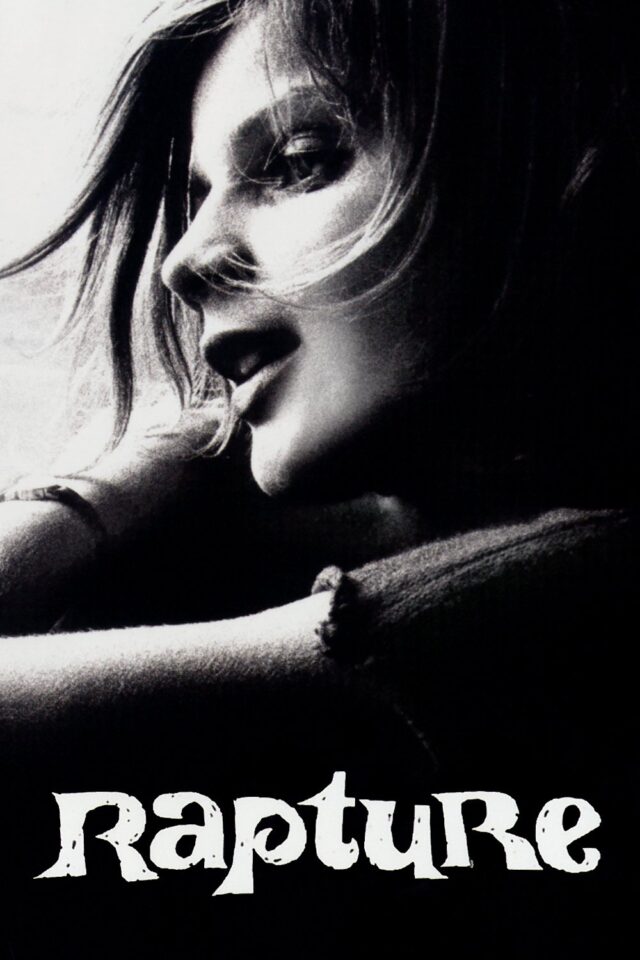

At the age of 62, Douglas’s film career shifted back into high gear, and he appeared in several notable films in the coming years, including “The Americanization of Emily” (1964) and the fascinating “Rapture” (1965), directed by John Guillermin. In 1967, he won his Best Actor Emmy for a CBS Playhouse episode called “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.”

In 1970, he earned his sole Best Actor Oscar nod for the caustic drama, “I Never Sang For My Father.” Douglas is riveting as a rigid, closed-off father whose son (Gene Hackman) desperately tries to break through to him when the family faces unexpected trauma. Douglas lost out to George C. Scott for “Patton.”

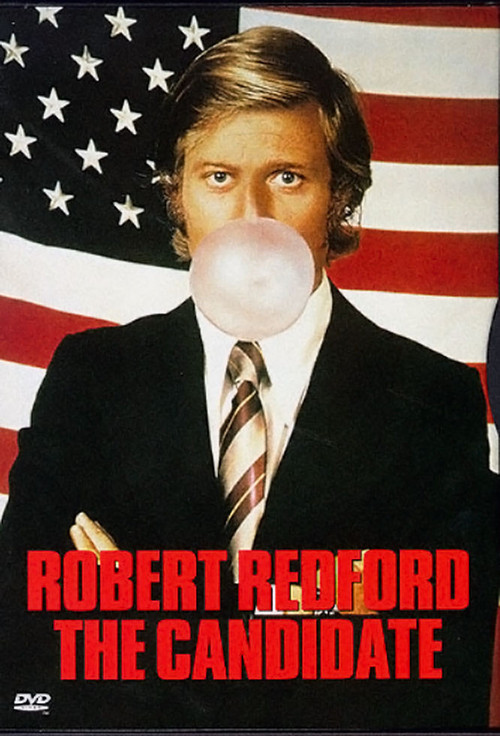

Now into his seventies, the actor hardly slowed down, appearing in such films as “The Candidate” (1972), “The Tenant” (1976), and “The Seduction of Joe Tynan” (1979).

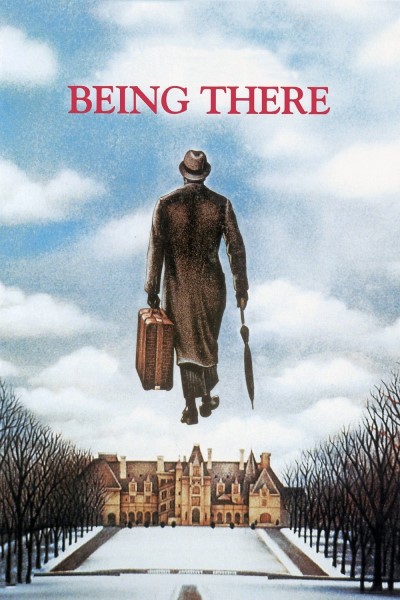

Then came the film that would bring Douglas his third Oscar nomination: Hal Ashby’s “Being There.” Douglas plays Benjamin Rand, a powerful Washington insider who comes under the spell of a simple gardener named Chance (Peter Sellers, in a career defining role).

Though Sellers was also nominated, it was Douglas who won the prize that night. He had now won two Oscars, with both coming after he’d reached the age of sixty. Having been frustrated by the shallow, predictable parts he’d been given as a younger man, he had finally managed to find the roles worthy of his talent later in life.

Melvyn Douglas died in 1981 of pneumonia and cardiac problems, less than a year after he lost his wife Helen to cancer. His brother, three children and six grandchildren survived him.

A kind, measured, and articulate man, Douglas set one firm rule that guided his life: “Don’t make excuses, and don’t talk about it. Do it.”

Melvyn Douglas did it. And we thank him for it.

More: How Peter Sellers Helped Mel Brooks When He Needed It Most