Few will ever forget this year’s Oscars, when Faye Dunaway read off the wrong card and mistakenly announced “La La Land” as Best Picture winner. Awkward as that was, there have been other memorably offbeat moments in Oscar history:

Having decided to boycott the ceremony in 1973, Marlon Brando sent up Native American activist Sacheen Littlefeather to accept his Oscar for “The Godfather.” Making the most of this highly visible platform, Ms. Littlefeather went on to decry the plight of American Indians, and their depiction in films. Judging by the chorus of boos that greeted her remarks, it was clear that this well-heeled industry crowd was in no mood to be lectured on this night of supreme self-congratulation. As a result of her controversial appearance, the Academy banned future award acceptances by proxy.

The very next year, with the witty, debonair actor David Niven at the microphone, a naked “streaker” ran across the stage right behind him, at which point Niven drily observed: “Isn’t it fascinating to think that probably the only laugh that man will ever get in his life is by stripping off and showing his shortcomings?”

Then in 1992, veteran actor Jack Palance, who after two prior nominations decades before, took the stage to accept the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role in the Billy Crystal comedy, “City Slickers.” After tossing off an amusing off-color joke (“Billy Crystal. I crap bigger than him.”) and observing how at his age many producers wonder whether he’s still fit to work, the 72 year-old wowed the jaded Oscar audience by executing a few one-handed push-ups.

Asked about it later, he said candidly, “I didn’t know what the hell else to do.”

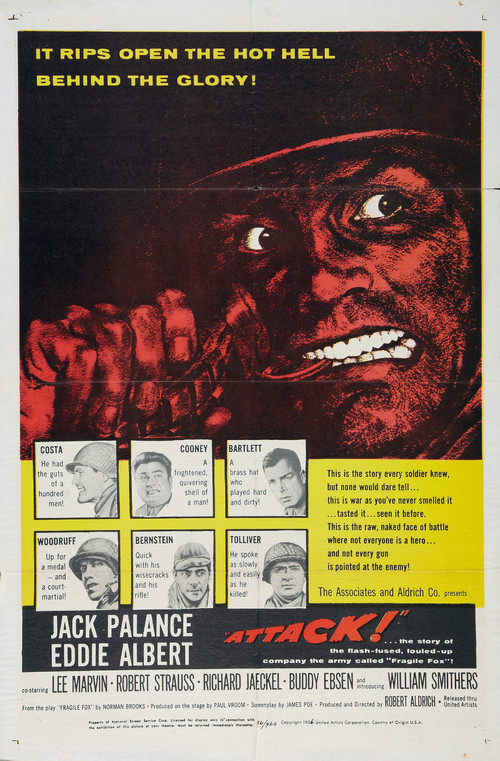

Jack Palance never had a problem getting noticed. A tall, powerfully-built man with squinty eyes and a broken nose, Palance was an imposing figure, on- and off-screen. (Tough guy Richard Widmark cited him as the only actor he’d ever worked with that he was physically afraid of).

Palance’s face mirrored the gritty, dangerous life he’d led before coming to Hollywood. He was born Volodomyr Pahlaniuk in Pennsylvania coal country, the son of Ukranian immigrants. One of six children, he followed his father into the anthracite mines before becoming a professional boxer. He achieved 15 consecutive wins and 12 knockouts before finally losing a bout on decision. Soon after he decided that the money wasn’t worth getting his head bashed in.

The Second War intervened and Volodomyr joined the Air Force. Reportedly, the beatings he’d taken to his face in the ring were nothing compared to the injuries he received when his B-24 caught on fire during a training run. That terrifying accident necessitated plastic surgery, which resulted in the face we’d all come to know. He’d earn a few medals for his service during the conflict, including the Purple Heart.

After the war, the young veteran enrolled at Stanford to pursue a journalism degree, and supported himself through a wide variety of jobs, including lifeguard, short-order cook, and photographer’s model. He quit one credit shy of graduating to pursue a career in the theater.

In a stunning feat of luck and timing, the strapping actor was hired (as “Walter Jack Palance”) to understudy Anthony Quinn’s Stanley Kowalski on the national tour of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” and eventually ended up on Broadway in the same position, ready to go on for Marlon Brando at a moment’s notice.

He and Brando shared an interest in boxing, and decided to set up a punching bag in the theater’s basement. One day, while the two men were working out, Palance’s fist accidentally connected with Brando’s nose. The star was out for enough performances to allow Jack to register in the part, and a contract with Twentieth Century Fox soon followed.

The young actor’s luck held, as his very first picture, “Panic in the Streets” (1950) paired him with top director Elia Kazan. Still billed with the first name “Walter”, the actor assumed the pivotal role of Blackie, a violent, small-time hood who, along with sidekick Zero Mostel, contracts bubonic plague. (Widmark plays the health inspector on his tail). Shot on location in New Orleans, the picture was a hit, and the studio started building up their new contract player in earnest.

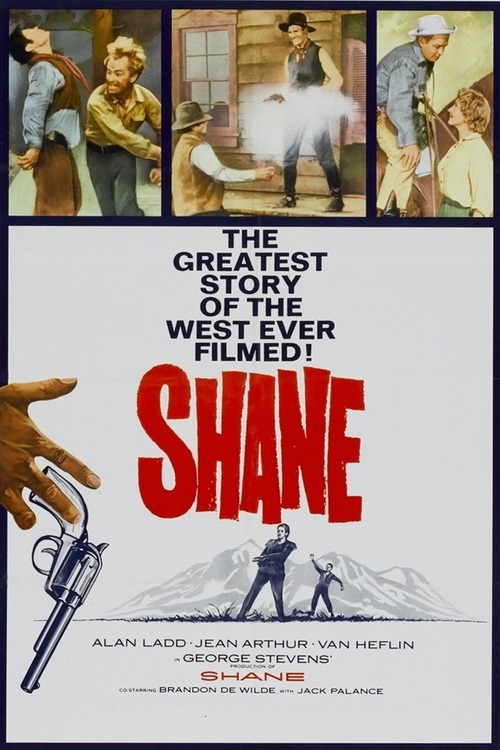

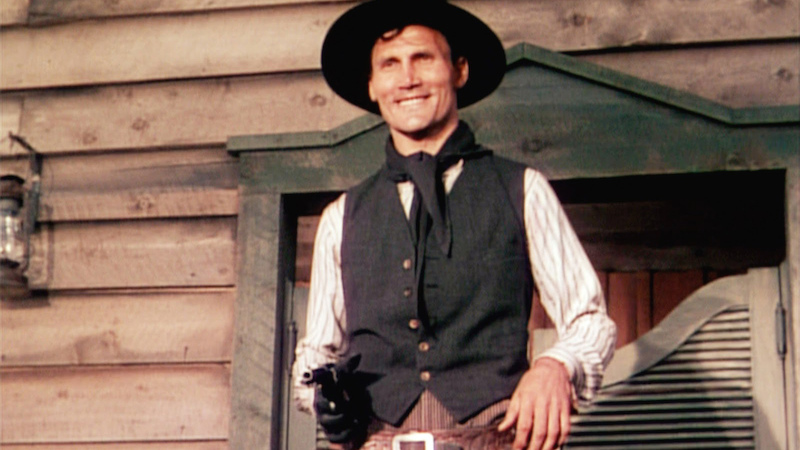

Soon after, legendary director George Stevens signed on to shoot a picture called “Shane,” his first Western in nearly twenty years. He needed someone to play a particularly cold-blooded killer named Wilson. Palance was cast in what would become his best-remembered role.

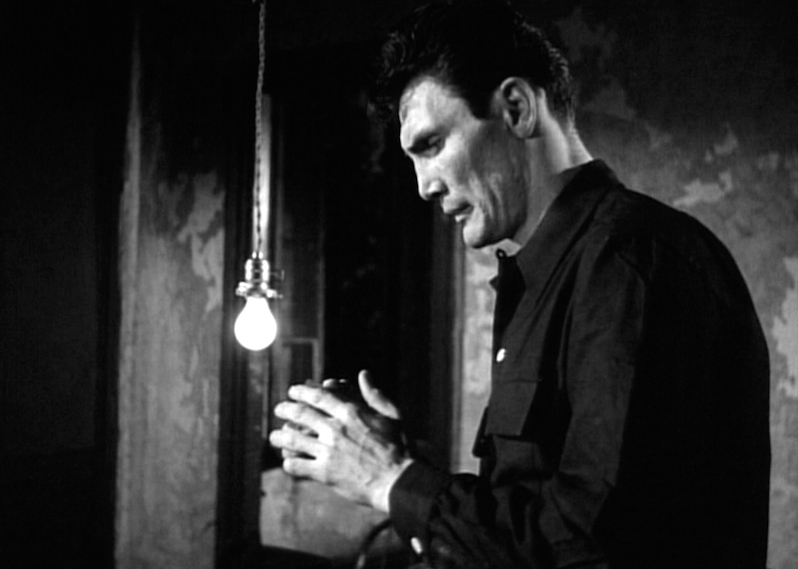

Having never appeared in a Western, Jack came to the “Shane” set with no knowledge of guns or horses. He worked hard to master both. But beyond his shooting and riding technique, it’s the sheer malevolence emanating from Wilson that explodes off the screen; he looks at his victims like they were his next meal, and almost slithers as he moves. Though short on dialogue, it remains an indelible portrait of pure evil.

In terms of memorable lines in the film, many cite the poignant ending where young Brandon de Wilde cries: “Come back, Shane!” Personally, I always remember the two short words Wilson says before pulling his gun: “Prove it.”

Though the movie was shot in 1951, it was not released till 1953 due to a prolonged editing process. (Palance would actually earn his first Oscar nod as Joan Crawford’s scheming husband in his next film, a superior thriller called “Sudden Fear.” He’d get his second consecutive nomination for “Shane” the following year).

In 1952, Kazan was about to shoot a historical drama called “Viva Zapata,” with Brando starring as Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. Palance was dying to play his brother Eufemio, and Kazan had basically promised him the part. Then he changed his mind and gave the role to Quinn, who Palance had understudied in “Streetcar.” Quinn would go on to win the Oscar for it (over Palance, nominated for “Sudden Fear”). Feeling betrayed, Jack never spoke to Kazan again.

In 1955, Palance appeared at the inaugural American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut, winning praise as Cassius in “Julius Caesar” and Caliban in “The Tempest.” Explaining Jack’s astonishing versatility on stage, producer Jack Haley, Jr. singled out the actor’s voice: “[It] is like a finely tuned musical instrument. It can whisper, roar, leer, shock, cajole, or ham it up. It ranges from a low, rumbling growl to medium-pitched urbanity.”

In a television broadcast the following year, Jack played down-and-out fighter Mountain McClintock in Paddy Chayefsky’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” and won an Emmy for his superb performance. However, when it came time to cast the film version, Anthony Quinn bested him again.

Still Jack needn’t have worried too much about the competition. Over the coming decades, he would achieve what every actor hopes for: he stayed busy, doing a combination of film, stage and TV work. Among other roles, he would end up playing Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, even Ebenezer Scrooge. (He also released an album of country-western songs in 1969). Besides “Slickers,” his later films included “Bagdad Café” (1987), “Young Guns” (1988) and “Batman” (1989).

Beyond his work, Jack had three kids with first wife Virginia Baker, one of whom, Cody, followed his father into acting. Jack’s daughter Brooke also became Elizabeth Taylor’s daughter-in-law when she married her son, Michael Wilding, Jr.

Yet Palance was not tied to the Hollywood scene. In the sixties, he started working extensively in Europe, and in later years, maintained a cattle ranch in Tehachapi, California and a home in Butler Township, Pennsylvania. With second wife Elaine Rogers by his side, he found time to paint landscapes and write poetry. He died peacefully in 2006 at his eldest daughter’s Montecito home. He was 87.

Roughly fifteen years before, Jack Palance had finally received his Oscar. That night, holding his award and doing those push-ups, he showed the world that he still had what it took. Yet it also felt like he was winning for his whole body of work. And that felt richly deserved.

More: The Sad History of Hollywood’s Wild One: Marlon Brando