Actress Shirley MacLaine once observed: “An actor has many lives and many people within him. I know there are lots of people inside me. No one ever said I’m dull.”

That’s for sure. Over the years, this irrepressible lady has sparked considerable bafflement and controversy over her outspoken views on reincarnation, extraterrestrials, and other New Age thinking.

But what of the on-screen Shirley? From the outset, it was clear she had an abundance of talent. But she had something more — a highly distinctive quality all her own. Indeed, when she burst on the Hollywood scene in the mid-1950’s, there was no one around remotely like her.

In an age of blonde bombshells like Grace Kelly and brunette goddesses like Elizabeth Taylor, Shirley was a decidedly boyish-looking redhead who cropped her flaming red hair short. Unlike these other stars, she was more cute than pretty, more kid sister than object of desire.

Still you couldn’t take your eyes off her. She was radiant; she was perky; she had “spunk.” But there were hidden depths underneath.

Shirley sensed her unique persona would serve her well over time. As she put it: “I wasn’t afraid of getting old, because I never had the problems the other actresses my age had. I was never a great beauty. I was never a sex symbol… I wasn’t interested in my stature as a star. Ever. I was just interested in good parts.” She always thought of herself as a character actress, even when playing leads.

She was born Shirley MacLean Beaty in 1934. Her father was a professor-turned-real estate agent, her mother a drama teacher. As if seeing the future, her parents named her for juvenile movie star Shirley Temple.

The Beaty family, which soon included son Warren, settled in Alexandria, Virginia. Noting that her daughter had weak ankles, her mother enrolled her in ballet school at a tender age, igniting Shirley’s lifelong passion for performing and dance.

Her unusual determination was evident early on when she broke her ankle backstage before a performance of “Cinderella.” Rather than bow out, Shirley danced that night, smiling through excruciating pain. After the show was over, an ambulance was finally called.

Eventually Shirley segued to musical comedies and straight acting while still in high school. Directly after graduating, she went to New York where she soon landed a plum job understudying star Carol Haney in the Broadway hit, “The Pajama Game.”

In a story right out of “42nd Street,” Haney broke her ankle while rehearsing, and Shirley was called on to replace her while she recuperated. One night shortly thereafter, top Paramount producer Hal Wallis happened to be in the audience, and was sufficiently impressed by what he saw to sign Shirley to a contract.

Fortuitously, she would make her screen debut in a Hitchcock film: “The Trouble with Harry” (1955). Shirley plays a single mother in a small Vermont town who, along with a few neighbors, must decide how to dispose of a body they’ve discovered. The fresh-faced newcomer was captivating, the film less so. Still, Shirley was noticed, winning a Golden Globe for most promising newcomer.

Hitchcock was known for forming an unhealthy obsession with some of his leading ladies (particularly the blonde ones), but this was not the case with Shirley. Instead, the famous director treated her like a daughter, having breakfast with her every morning before shooting began. Having first observed a thin, struggling chorus girl who clearly didn’t eat properly, his goal was to fatten her up. Though she gained almost 15 pounds as a result of his intervention, it hardly showed.

By this time, Shirley was already married to businessman Steve Parker. They would maintain an open marriage until their divorce nearly twenty years later, with Parker serving as primary caregiver for their daughter Sachi, born in 1956. From the beginning, it was understood that Shirley’s work and career would take priority.

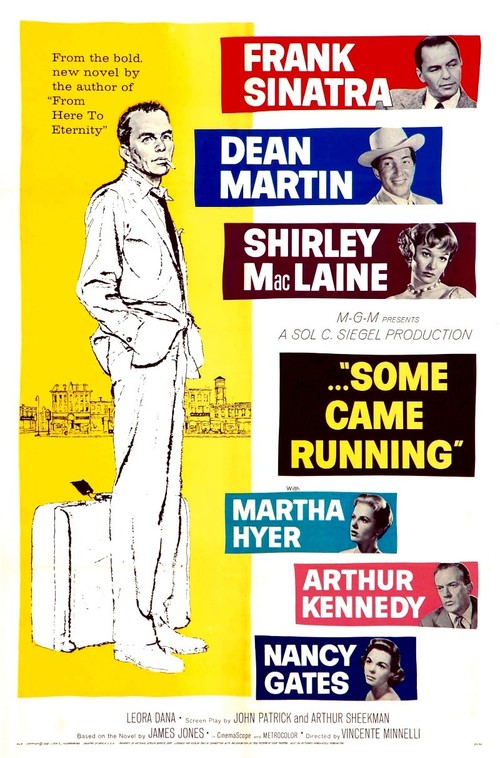

In 1958, Shirley won her first Oscar nomination for Vincente Minnelli’s “Some Came Running,” playing a loose but fragile young woman in yet another small town who falls for troubled veteran Frank Sinatra. This production, which brought her close to both Frank and co-star Dean Martin, would result in her becoming the sole honorary female member of Sinatra’s “Rat Pack” (a/k/a “The Clan”).

Two years later came Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment.” Her Oscar-nominated portrayal of Fran Kubelik, an elevator girl manipulated by a married senior executive in Manhattan’s corporate jungle, was among the finest work she’d ever do on-screen. She was barely 25.

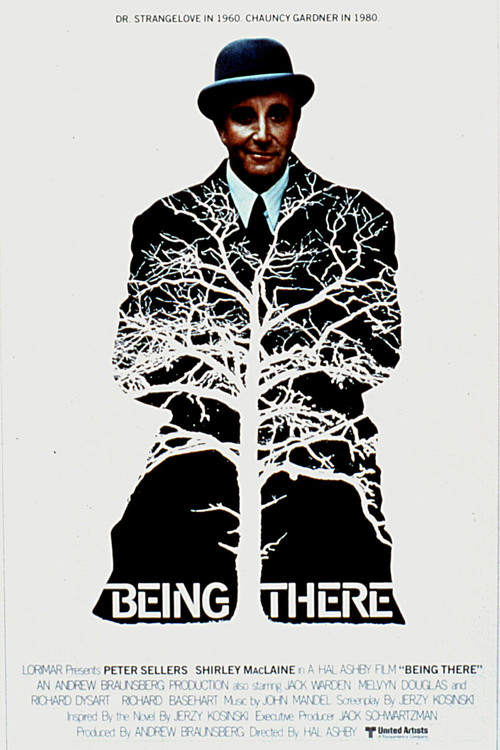

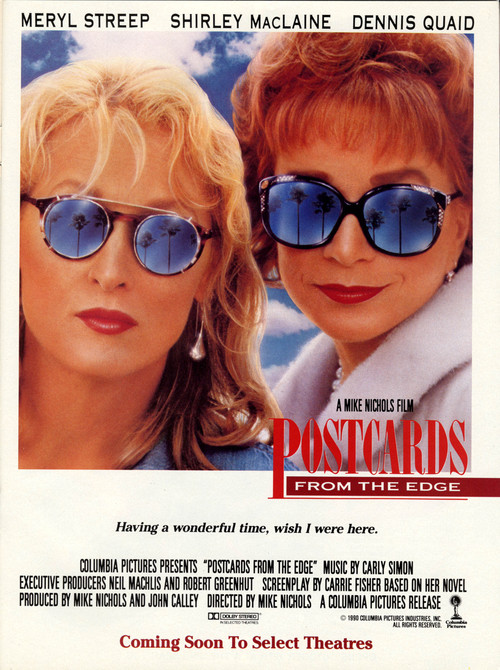

In the years that followed, Shirley would star in many more memorable, high-profile movies like “Irma La Douce” (1963), “Sweet Charity” (1969), “The Turning Point” (1977), and “Postcards from the Edge” (1990). She’s been Oscar-nominated six times and finally won at age 50, playing Debra Winger’s mother in 1983’s “Terms of Endearment.”

Shirley has stayed active, both in film and on television. Her small screen work has yielded five Emmys for her variety specials (and one miniseries). For both film and TV work spanning over half a century, she has amassed 20 Golden Globe nominations and seven wins, including the prestigious Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1998. (A new generation was introduced to her on the popular series “Downton Abbey” in 2012).

While admiring Shirley MacLaine’s staying power, I reserve a special fondness for her early roles. If I watch “The Trouble with Harry” or “Some Came Running,” I watch it to see her. In those movies, Shirley MacLaine was the girl next door I wanted next door.

And though “The Apartment” is often identified as Jack Lemmon’s first dramatic showcase, we should never discount Shirley’s note-perfect performance. At the end of that unforgettable film, when Lemmon’s character C.C. Baxter says to her, “I absolutely adore you,” he is not alone. Every man in the audience is right there with him.