Henry Fonda once confided that the characters he played on-screen bore little resemblance to himself. Rather, they were who he’d like to be, if he could.

By most accounts, except with his closest friends (like Jimmy Stewart), he was a cold, aloof man terrified of betraying emotion. Many of those who worked with him felt his remoteness. Reportedly, until late in his life his own children, Jane and Peter, never really knew how he felt about them. For him, showing or expressing affection was strictly off-limits.

Extremely shy from childhood, Henry (known as Hank) was drawn to the theater in his early twenties as a “way to put on a mask.” He began to appear on stage in his native Omaha, and his first real acting teacher was none other than Marlon Brando’s mother.

He soon traveled East to seek his fortune, and landed with the University Players in New England, where he met his first (of five) wives, Margaret Sullavan. Inevitably, Fonda was drawn to New York City and the mecca of Broadway, where he made the rounds and paid his dues. These were lean times, particularly with the onset of the Depression, but the young actor finally broke though in a play called “The Farmer Takes A Wife.”

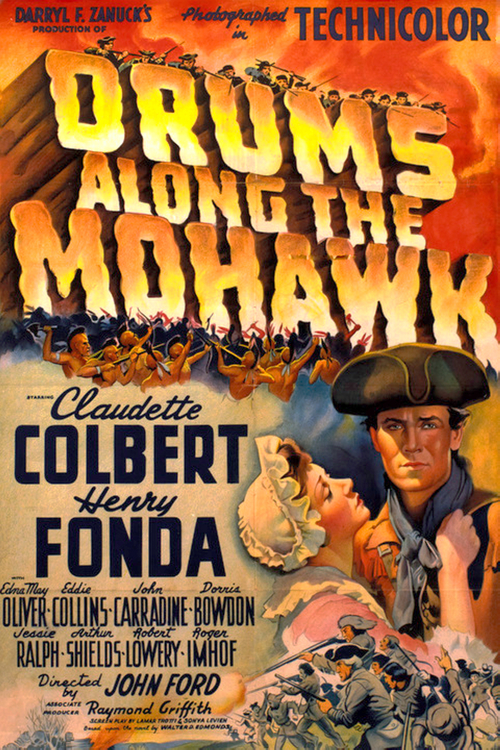

In 1935, he made the move to Hollywood to reprise the role in the movie version, and his film career was launched. By this time, he’d married his second wife, Frances Brokaw, mother of Jane and Peter. Within several years, Fonda’s stardom was assured with roles in “Jezebel” (1938) and John Ford’s “Young Mr. Lincoln” (1939).

The following year brought one of his finest performances as Tom Joad in “The Grapes of Wrath,” a part that almost went to Tyrone Power. To get the role, Fonda was forced to sign a seven-year contract with 20th Century Fox. “Grapes” brought him his first Oscar nomination, but his old friend Jimmy Stewart beat him out for “The Philadelphia Story.”

The Second World War then intervened, and after making a fabulous Western called “The Ox Bow Incident” (1943), Fonda enlisted in the Navy, and saw action in the Pacific Theater, earning a Bronze Star in the process.

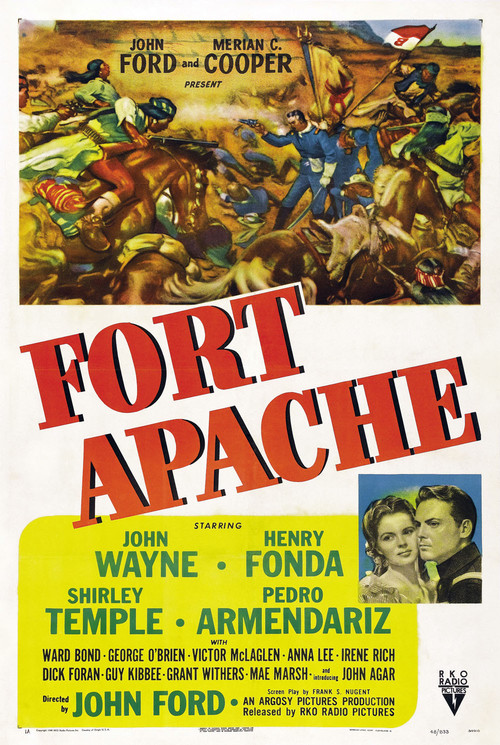

On his return to civilian life, Fonda took his time getting back into film, eventually re-teaming with director John Ford for the classic Western, “My Darling Clementine” (1946). He’d then go back to the stage to create another indelible role, a frustrated Naval officer on a cargo ship desperate to see action in World War 2. The play was called “Mister Roberts,” and once again Fonda would recreate the character on-screen years later.

Fonda had become disgusted with the unjust practice of Hollywood blacklisting in the late forties and early fifties, and kept his distance from the film industry over this period, focusing on theater and television. He and Jimmy Stewart almost ruined their friendship at this point, getting into an explosive argument about McCarthyism. Stewart was a right-wing hawk, Fonda a loyal, left-leaning Democrat. They finally agreed never to talk politics again.

“Mister Roberts” (1955) would be Fonda’s first feature film in seven years. It was during this production that he and director John Ford crossed swords, and the temperamental director sucker-punched Fonda. Ford was fired and replaced by Mervyn LeRoy, and sadly, the two past collaborators never spoke again. Fonda would always praise Ford’s talent with a camera, but he also described him as an “egomaniac.”

By this point, Fonda’s third marriage to Susan Blanchard was starting to unravel. Second wife Frances, long beset by emotional problems, had committed suicide shortly after Fonda had asked for a divorce in 1950.

With the success of “Mister Roberts,” which drew a Best Picture nomination, Hank returned to the big screen in a big way. And yet, for perhaps his finest hour, he chose a very small film and a first-time director named Sidney Lumet. Fonda both produced and starred in Lumet’s ensemble piece, “12 Angry Men.” Though this film, mostly shot on a single set, never made money, it won tremendous acclaim and is now considered a classic.

Henry Fonda would stay busy for another 25 years, notably playing against type a cold-blooded killer in Sergio Leone’s “Once Upon A Time In The West” (1968), and winning a Tony Award for essaying the title role in “Clarence Darrow” on Broadway in 1974. His biggest regret over this period was not getting the chance to play George in Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?” He’d been offered the part for the original Broadway production, but his agent had turned it down without even showing it to him.

After “Darrow,” Fonda started experiencing symptoms of the heart ailment that eventually killed him, and decided to retire from the rigors of live performing. He still stayed active in TV and film, however.

He was finally teamed with his contemporary Katharine Hepburn and daughter Jane in Mark Rydell’s “On Golden Pond” (1981), and on-set, it was clear his health was failing. When his name was called out for Best Actor at the 1982 Oscar ceremony, his daughter Jane accepted the statuette for him. Fonda died just a few months later, at the age of 77.

In his last years, he’d finally managed to tell his children he loved them.

Henry Fonda’s ability to project the best of the American character: decency, humility, solidity, made him an icon. But to his credit, Fonda was well aware of his own shortcomings, and fully recognized the divide between the characters he played and the real man.

Tellingly, he once said: “I hope you won’t be disappointed. You see, I am not a very interesting person. I haven’t done anything except be other people. I ain’t really Henry Fonda! Nobody could be. Nobody could have that much integrity.”

Hank, we understand. And no you didn’t disappoint us. You never disappointed us.

More: “12 Angry Men” — How to Make a Great Film on a Tiny Budget