Humphrey Bogart was once asked if he had any difficulty putting aside his tough image to play a romantic leading man in “Casablanca” (1942). He said it was easy. “It helps,” Bogie said, “if you’re looking into the eyes of Ingrid Bergman.”

Perhaps other actresses were more brazenly sexy, but few had Ingrid Bergman’s combination of beauty, elegance, and pure acting talent. She was not your typical Hollywood starlet.

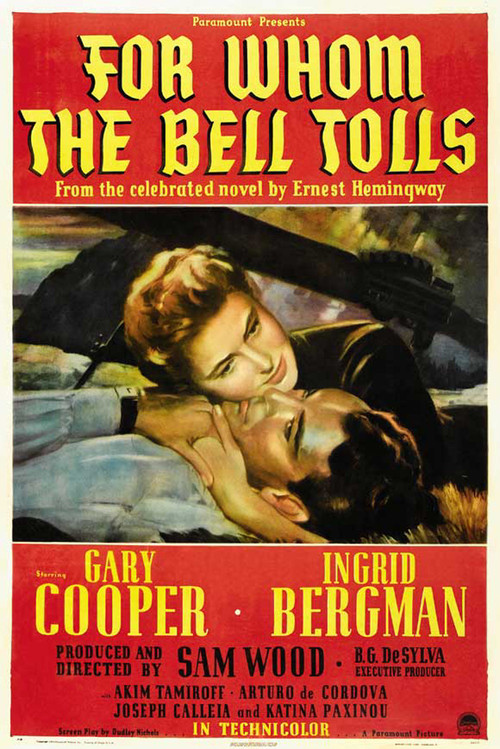

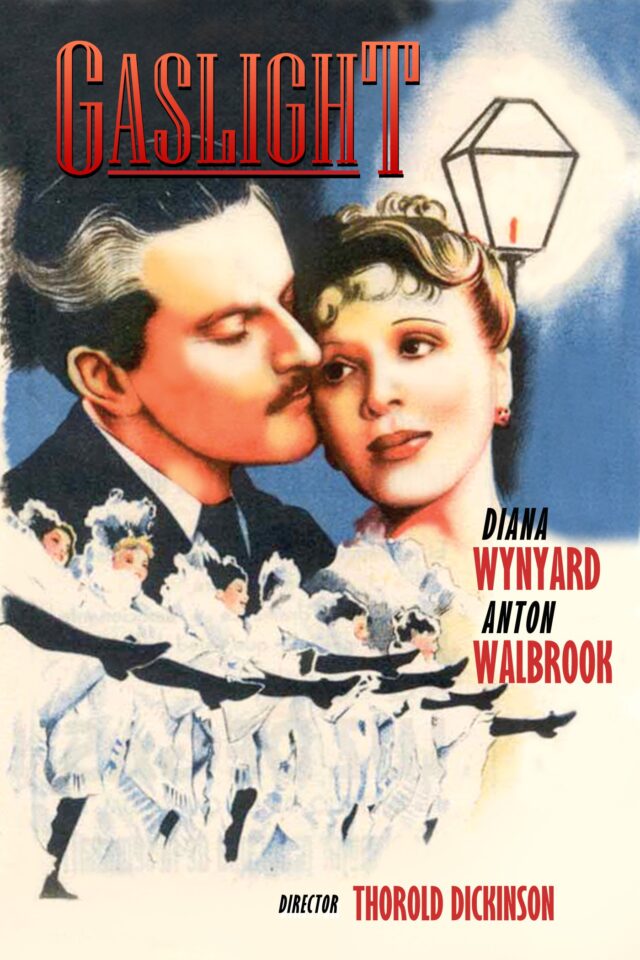

Ingrid had a tough start. Growing up in Sweden, she’d lost both her parents by the time she was 12. At 18, after being raised by an uncle who encouraged her interest in theater, she embarked on an acting career that would make her internationally famous and earn her two Best Actress Oscars — one for “Gaslight” (1944), and one for “Anastasia” (1956).

By the time she picked up a third statuette, this one for Best Supporting Actress in “Murder On The Orient Express” (1974), she’d become a legend. The ovations that greeted her whenever she appeared at film festivals or award ceremonies were thunderous. In fact, she was winning awards even after her ashes were scattered off the coast of Sweden; her television portrayal of Golda Meir, made while she was suffering from the cancer that would kill her at 67, earned her an Emmy.

Her creative gifts were accompanied by a tough and practical business sense that often caught people by surprise. When producer David O. Selznick told 23-year-old Ingrid that she would have to change her name, cap her teeth, and pluck her eyebrows, she said she’d rather return to Sweden. It’s a good thing Selznick relented, since it’s hard to imagine Hollywood in the 1940s without Ingrid. It’s even harder to conceive of “Casablanca” without her playing the romantically torn Ilsa Lund.

Although millions of film fans love “Casablanca,” Ingrid often dismissed it as one of her least favorite roles. Her hesitancy to embrace “Casablanca” partly stemmed from all the chaos behind the scenes. Both Bogart and Ingrid were unhappy with the script, which was being constantly worked on as shooting progressed. To make matters worse, Bogart’s wife at the time, alcoholic actress Mayo Methot, embarrassed everyone by storming onto the set and loudly accusing Bogie and Ingrid of having an affair. Nothing could be further from the truth; as Ingrid said of Bogie, “I kissed him, but I never knew him.”

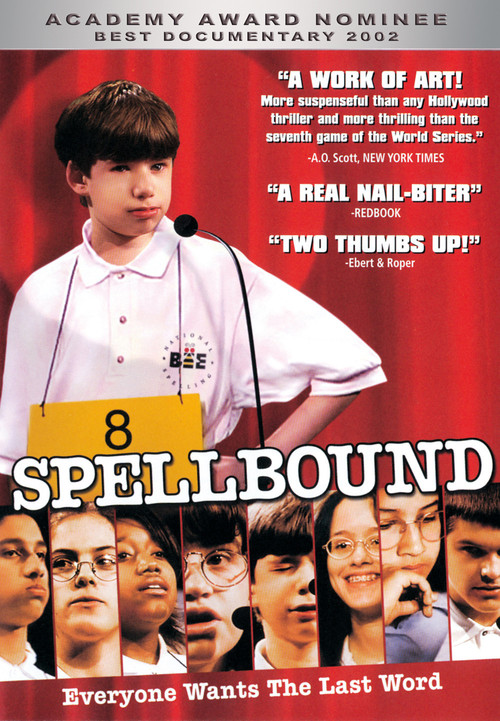

Ironically, from this caustic atmosphere emerged a classic film that was chosen by the American Film Institute in 2002 as the greatest American love story of all time. We can just hear Ingrid now: “Are they still talking about that silly movie?” The truth is, she knew “Casablanca” was special — she just hated how it overshadowed all her other work.

The off-screen romance with Bogart may have been a figment of Methot’s imagination, but there would come a time when Ingrid’s love life would turn the public against her. The backlash happened in 1950 when the married Ingrid had a scandalous affair with director Roberto Rossellini, with whom she was filming “Stromboli” in Italy. Pregnant with Rossellini’s child, she left her first husband and daughter Pia in America. The straitlaced American press was outraged.

Ingrid’s fall from grace had a bright side, however – while the puritanical forces in her adopted country railed against her, she married Rossellini and had a family (including model/actress Isabella Rossellini). She also took a prolonged break from Tinseltown to make films in Europe.

The scandal was both a testament to Ingrid’s appeal as a star and her steely independence as a woman. The enormous uproar came from the revelation that one of America’s most beloved actresses wasn’t a saint, even though she’d played one (in 1948’s “Joan Of Arc”). Ingrid bore it all with her accustomed dignity and grace.

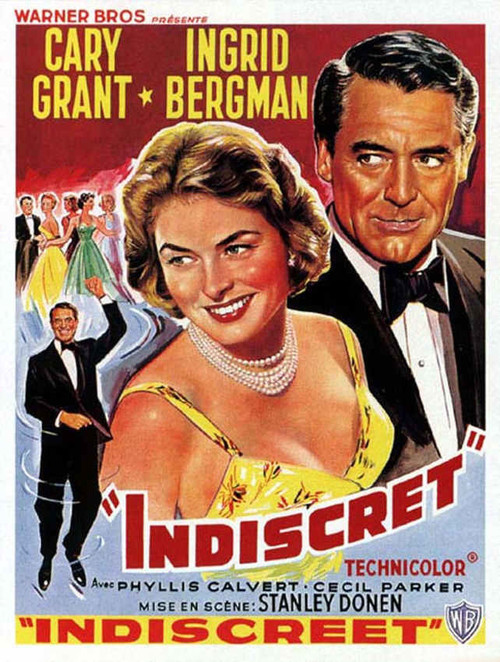

And of course, the exile didn’t last. By 1956, Ingrid was back in Hollywood, her popularity seemingly undiminished. The fickle public had not only forgiven her, but desperately craved her luminous presence once again.